Introduction

In the early 1990s a red book sized disc promised to change everything about home gaming. The Sega CD arrived with glossy full motion video, big stereo sound, and enough storage to make cartridges look quaint. It was marketed as the bridge between arcade energy and living room cinema. For a moment it worked. You could spin compact discs in your console, watch grainy actors run through a haunted house, and imagine a future where games felt like late night cable.

(HEY YOU!! We hope you enjoy! We try not to run ads. So basically, this is a very expensive hobby running this site. Please consider joining us for updates, forums, and more. Network w/ us to make some cash or friends while retro gaming, and you can win some free retro games for posting. Okay, carry on 👍)

That same moment also put the industry under the brightest spotlight it had ever faced. Night Trap, a campy interactive movie packaged for the Sega CD, became a national flashpoint after senators watched a few out of context scenes and saw a moral emergency. In less than a year, hearings in Washington led directly to the creation of a formal rating board for games. Retailers yanked copies from shelves, newspapers ran front page stories, and parents demanded answers. The conversation did not stop at one controversial title. It forced the entire business to explain itself to the public and to the government.

This is the story of how a bold piece of hardware and one sensational game helped push the medium into a new era of self regulation. It begins with the engineering and ambition behind the Sega CD. It moves through the production and release of Night Trap. It culminates with the hearings that birthed the Entertainment Software Rating Board. Along the way we will separate myth from memory, show how retailers and platform holders reacted, and track how the standards set in 1994 still shape the screen time in every modern home. For sources, you will find inline links throughout, and community threads you can screenshot for extra flavor.

Before we dive in, picture the scene. A chunky television humming with scanlines. A Genesis stacked under that brand new disc drive, its tray light glowing like a tiny marquee. Pizza boxes on the floor, a manual tossed aside, and friends arguing about who gets the controller during the bathroom scene. It was messy and magical and completely new, and it set the stage for a cultural moment nobody in that living room could have predicted.

What the Sega CD Was

Sega’s add on was conceived to leap beyond cartridges and into the world of optical media. The unit launched in Japan in December 1991 and reached North America in October 1992, bringing a faster coprocessor, extra memory, and a custom graphics chip that enabled sprite scaling and rotation tricks that felt close to arcade effects of the time. It plugged into a Genesis, required its own power, and turned the system into a hybrid that could spin both game discs and music. The official entry lays out the dates, the hardware, and the feature set in clear detail.

Storage was the real revolution. A compact disc could hold more than six hundred megabytes, hundreds of times the capacity of a typical Genesis cartridge. That kind of space made full motion video feasible and invited developers to experiment with cinematic presentation. It also created an early wave of ports that simply used the disc for arranged soundtracks or bonus scenes. Sega’s own page notes the split legacy. There were acclaimed titles like Sonic CD and the Lunar role playing series, but there were many shallow conversions and a rush of live action experiments that did not always deliver deep play.

The system mattered for more than games. It treated the living room console like part of a home stereo stack. The unit could play audio CDs and CD plus G discs for karaoke. Later variants fused the concept even tighter. The Genesis CDX proved the point in a single compact shell, but the star of this story is still the add on itself and what it made possible on day one. The boombox style Aiwa CSD GM1 showed how far that multimedia idea could travel into everyday living rooms. These touches underline how seriously manufacturers took the notion that a game machine could also be a media hub.

Setup nights felt like a ritual. You scooted the console a little to the left, clicked the expansion port into place, and fished for an open outlet because that brick needed its own plug. Then came the reward. A clear clack from the tray, the disc label spinning into view, and a splash screen that practically shouted you were stepping into tomorrow. It was not just about polygons or parallax anymore. It was about showmanship.

The CD Lawnmower Was Already Running

Sega’s push did not happen in a vacuum. NEC and Hudson had beaten everyone to optical media with the PC Engine CD ROM two add on in 1988. That expansion brought CD based games, compact disc audio for music playback, and even CD plus G support to living rooms years before Sega’s unit. The TurboDuo, a combined console and CD player sold in North America, could read standard audio CDs and CD plus G discs out of the box. That context matters because it shows that a wave was building across the industry and Sega jumped in to keep up rather than invent the format.

The arrival of discs changed expectations around game soundtracks and presentation. Red book audio meant music that could live outside the game. Players discovered they could drop a disc like Sonic CD into a regular stereo and hear the soundtrack as an album, something that still delights collectors and preservationists. It is easy to forget how radical it was to play a game disc in a hi fi and get legitimate new music instead of beeps and loops. That cross pollination between the music shelf and the console shelf became part of the CD era’s everyday life.

Sega’s device was not cheap and sales never matched the hype. The official history shows a global total a little above two million units before the company moved on to Saturn. Yet even with that modest footprint, the add on injected new ideas across the market. It taught platform holders to treat sound and video as headline features. It gave developers a reason to film actors, build sets, and push toward narrative ambition. It also provided the stage for the game that would drag the entire industry into a hearing room.

Think back to the first time you slid a game disc into a stereo just to see what would happen. That tiny act felt like mischief and discovery at once. The CD age encouraged that curiosity and fed the imagination of both players and studios. It was a playground and Night Trap was about to become its most notorious attraction.

The Making of Night Trap

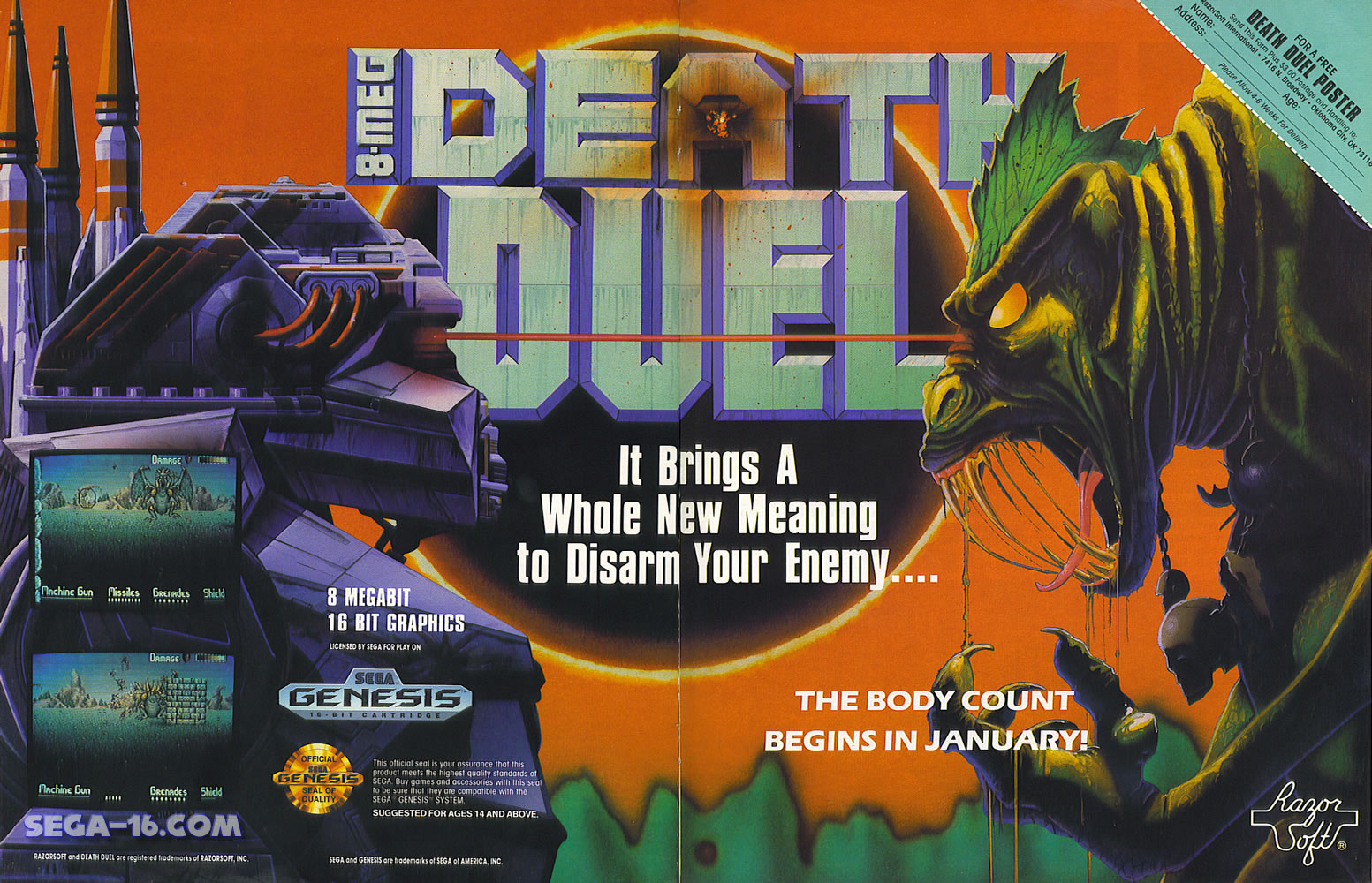

Night Trap was born before the Sega CD existed. In the late 1980s a team working with Hasbro experimented with an interactive system that used VHS tape to switch between multiple video channels. Producer Tom Zito acquired the footage when that platform was canceled and later founded Digital Pictures to finish the concept for the CD age. The game finally emerged in November 1992 as a North American launch title for Sega’s CD add on. The development timeline and the technology shift from analog tape to CD are well documented.

The concept played like a B movie with player agency. You jumped between surveillance cameras inside a house, listened for audio cues, and sprung traps to catch shuffling intruders called Augers before they could harm the teenage guests. The tone leaned toward spoof rather than splatter. Designers have said repeatedly that the gag was saving the cast, not hurting them, and that the blood draining devices were made intentionally absurd to avoid realistic violence. That nuance would be lost in the political storm to come, but it helps explain why early reviews often praised the humor even as they criticized the shallow timing based play.

For the twenty fifth anniversary, a modern remaster brought back cut scenes, a prototype for a related idea, and a wealth of behind the scenes material. Interviews with the team and with the remaster studio confirm just how long the game’s odd journey took, and how much of its reputation was shaped by what happened after release rather than by the quiet first months on store shelves. If you want texture for a sidebar or a caption, those retrospective pieces are a goldmine.

Playing it in the 1990s felt like hosting a cheesy midnight movie in your own den. You were the unseen director. You were the person riding the switchboard, flipping rooms, and closing the trap at the last second while your friends yelled from the couch. It was part television and part toy and one hundred percent perfect for getting parents to walk in and ask what on earth you were doing.

The Senate Puts Games on Trial

On December nine 1993, senators Joe Lieberman and Herb Kohl convened a hearing on violent video games. The targets were Mortal Kombat and Night Trap, framed as examples of a medium that had slipped into unacceptable content. The official summary of the 1993 and 1994 sessions describes how the committees pressured the industry to do something on its own or risk federal regulation. It also captures the competitive tension between platform holders that made the spectacle even louder.

Nothing illustrates the atmosphere better than the primary footage. C SPAN hosts the original hearing videos where you can watch senators hold up light gun peripherals and denounce specific scenes. The clips that travel most often include the still of Senator Lieberman brandishing a plastic revolver and the moments where he describes an imagined bathroom attack. You can link straight to the archive if you want to embed a snippet or pull still images for a collage.

The rhetoric traveled far beyond the room. Nintendo executive Howard Lincoln used his time to say that Night Trap would never appear on a Nintendo system because it would not pass his company’s standards. That line followed him for decades, only to look quaint when a remastered version later arrived on Switch. Polygon’s explainer collects the quote and the full context, making it an easy reference to pair with your own commentary and the later reversal.

Watching those clips now is surreal. A cartoonish vampire romp became the centerpiece of a national conversation. The game was treated like a cultural threat, a miniature movie accused of teaching the wrong lessons, and Night Trap suddenly carried the weight of an art form in the middle of a moral panic.

Sega’s Head Start on Ratings and the Rivalry on Display

Sega did not walk into the hearing empty handed. Months earlier it had launched the Videogame Rating Council, a three tier label that marked games as general audiences, mature audiences thirteen, or mature audiences seventeen. The ESRB’s own oral history acknowledges that Sega created the VRC in June 1993 as a way to signal to parents that not every title was meant for every child. The Wikipedia entry on the hearings also notes the system and captures how Nintendo refused to use it, citing both rivalry and different corporate philosophies.

Press coverage during that winter recognized the scramble to find an industry wide answer. A Washington Post report in December 1993 described the coalition talks and pointed out that Sega had already placed warning badges on boxes while Nintendo leaned on stricter submission guidelines for family friendly content. You can see the differing strategies clearly. One approach was to rate and sell across a wider age range. The other was to police the catalog tighter at the platform gate. The hearing forced both viewpoints into the same frame.

This rivalry contributed to some of the most quoted moments. Lincoln’s promise that Night Trap would never arrive on a Nintendo machine made for great television and positioned Nintendo as the moral voice. Sega executives countered by arguing that the average game buyer was older than critics assumed and that ratings made more sense than blanket bans. When you read the transcripts and the reporting side by side, it becomes clear that the politics of competition and the politics of content converged in one room.

The beauty of that rivalry is how it pushed games to grow up in public. Sega took the measure of its audience and argued that labels beat limits. Nintendo doubled down on curation and presented itself as a guardian of living room values. The push and pull helped shape a compromise that is still visible on every box and every store page today.

Retailers Pull the Game, Sales Spike, and Sega Blinks

The hearings did not bury Night Trap. They made it famous. Digital Pictures founder Tom Zito later said that the game sold fifty thousand units in the week after the first session. That is the paradox of controversy in entertainment. News cameras can turn a niche product into a must see oddity overnight. The hearing summary cites Zito’s figure and places it right next to the next plot point.

Toy chains then made their move. Toys R Us and Kay Bee Toys removed Night Trap from stores two weeks before Christmas after a flurry of complaints from parents. The New York Times covered the decision as a national consumer story and treated it as the first major retail consequence of the hearings. The pattern was clear. Politicians turned up the volume. Families called store managers. Corporate policy followed, fast. For a direct record of the decision, The Washington Post article that announced Sega would withdraw and revise the title in January is essential reading.

- Night Trap Screenshot

- Night Trap Screenshot

- Night Trap Screenshot

For extra color you can grab community memories and images from retro threads where collectors share box art variants and discuss the later re releases. The r NintendoSwitch community memorialized Howard Lincoln’s promise with posts that resurfaced when Night Trap finally appeared on Switch. The result is a layered timeline that moves from Senate citations, to mainstream press, to fan recollection, and back again to modern remasters.

Anyone who walked the toy aisles that winter remembers the strange mix of absence and demand. Empty shelf tags. Clerks shrugging. Phone calls from parents who heard about a dangerous game and kids who just wanted to try the funny vampire one everyone was talking about. That is how a ratings era is born, not through theory but through messy weekends at the mall.

The ESRB Arrives and Changes the Shelf

The solution that let the industry keep control was a formal rating board with standardized icons and descriptors. The organizations that represented publishers created the Entertainment Software Rating Board in 1994. The ESRB’s own history page lays out the founding date and the initial five categories, which later evolved as platforms and audiences changed. What matters for a modern reader is that the structure devised thirty years ago is still in place and still shapes how stores stock and how parents buy.

Coverage from the period captures how quickly the business moved once Washington applied heat. In July 1994 publishers proposed the board to Congress and set a launch date for the fall. By September the system was operational. A Wired retrospective explains the timeline and how the threat of legislation pushed voluntary compliance into reality. The best part of the story is that it made retailers comfortable again. With a consistent label on each box, stores could answer parent concerns at the register.

By the end of the year, both console and computer games had rating paths. Another Wired feature from 1994 describes how the two camps built parallel codes and how free speech concerns hung in the background. You can feel the tug of war between art, commerce, and politics in every paragraph. The basic idea held. Inform the customer clearly and let the market decide. That bargain allowed creative risk to continue while giving families an easy filter.

Those little badges did more than calm a storm. They normalized the idea that games could be for different ages and tastes without turning into a shouting match each holiday season. They also gave developers a clearer runway to take risks, because the expectation setting moved to the front of the box instead of the nightly news.

What the Sega CD Experiment Left Behind

The add on faded as new hardware arrived, yet its impact outlived the plastic. It proved that players value music and video quality alongside mechanics. It seeded a library of soundtracks that people still spin outside the game context. Most of all, it set the stage for a culture shift that went far beyond one platform. Sega CD opened the door for live action experiments like Night Trap, and Night Trap opened the door to a national conversation that wrote new rules for everyone.

The same experiment also exposed the limits of chasing film. Many full motion video projects felt like novelties without replay value. That is not a condemnation. It is an honest read of a first generation trying to find a grammar for interactive cinema. Reviews and retrospectives record the shallow mechanics and praise the few games that found a stronger balance. The lesson traveled forward. Later generations focused on blending authored scenes with player agency rather than locking progress behind perfect trap timing.

Most importantly, the Sega CD gave the industry its loudest case study for how content scares can escalate. Night Trap was silly, a little sleazy, and very 1992. It was also the perfect foil for a political moment that needed a villain. The hearings turned a quirky launch title into a household name. The fallout birthed a system that still sits on every product page and storefront card. That is an outsized legacy for a peripheral that sold a couple million units. It shows how technology, culture, and policy can collide in a single season and set rules that last for decades.

Here is the punch line that never gets old. A quirky FMV about cable ready vampires helped standardize the rating stickers that guide every purchase your family makes today. That strange alchemy of tech trend, cult game, and public hearing changed the shelf for good and proved that games could police themselves without losing their spark.

Conclusion

The Sega CD tried to turn consoles into multimedia hubs and, for a short time, it succeeded. Night Trap tried to turn a campy horror flick into an interactive toy and, for a much longer time than anyone expected, it succeeded too. Together they pushed games into the halls of Congress and forced a conversation about who games are for and how clearly that should be labeled. The answers produced the ESRB and a template for voluntary ratings that kept lawmakers at bay while giving households a practical tool.

Look at your modern storefront. Every page carries a rating badge and a list of content descriptors. Every trailer campaign takes those labels into account. The groundwork was poured during the season when a single live action vampire caper made America ask what its kids were watching. The discs have yellowed. The hardware belongs in glass cases. The rules that grew out of that moment are still with us.

So the next time you fire up a digital store and glance past those tiny icons, remember the whir of a disc tray and the laughter in a living room where friends tried to spring traps at the perfect second. Night Trap and the Sega CD made a loud, goofy, unforgettable case for why games needed clear labels, and that is why their legacy still hums beneath every modern click of the buy button.

Retro Replay Retro Replay gaming reviews, news, emulation, geek stuff and more!

Retro Replay Retro Replay gaming reviews, news, emulation, geek stuff and more!