Legends never die

When most people think about video game history, they picture the giants. The Nintendo Entertainment System that revived the industry in the eighties. The Sega Genesis and the Super Nintendo that waged the fiercest console war of the nineties. The Sony PlayStation that turned gaming into a cultural juggernaut. The Microsoft Xbox that reshaped online play in the 2000s. These names are immortal, and for good reason. They sold millions of units, introduced unforgettable franchises, and became the centerpieces of living rooms across the world.

(HEY YOU!! We hope you enjoy! We try not to run ads. So basically, this is a very expensive hobby running this site. Please consider joining us for updates, forums, and more. Network w/ us to make some cash or friends while retro gaming, and you can win some free retro games for posting. Okay, carry on 👍)

But there is another story, written between the lines. For every system that soared, there were others that stumbled. They arrived with ambition and unique ideas, yet they failed to secure a foothold in the marketplace. Some were criticized at launch, others quietly faded away, and many were labeled as outright failures. Yet if you look closer, you will see that these machines carried sparks of innovation that eventually lit the path for future generations. They were not simply missteps, they were experiments, and their influence is still with us today.

In this feature we will explore four such systems: the TurboGrafx-16, the Atari Jaguar, the 3DO Interactive Multiplayer, and the Sega CD. These consoles are often remembered for their struggles, but they also introduced technologies, genres, and cultural shifts that shaped the future of the industry. From the first widespread use of CDs to the birth of Rayman, these so-called failures played a role in making gaming what it is today.

TurboGrafx-16 / PC Engine

The TurboGrafx-16, known in Japan as the PC Engine, was released in 1987 in its home market and in 1989 in the United States. Created by NEC in collaboration with Hudson Soft, the system was small and compact, but its technical design set it apart from the competition. It combined an eight-bit CPU with dual sixteen-bit graphics processors, which allowed it to produce vivid colors and smooth scrolling that the Nintendo Famicom could not match. Many players considered it the first true challenger to Nintendo’s dominance (Wikipedia).

One of the most important innovations came only a year later. In 1988 NEC released a CD-ROM add-on for the PC Engine, making it the first home console to use optical discs. This single decision changed the trajectory of gaming forever. Developers now had far more storage than a cartridge could provide. Games could include animated cutscenes, orchestrated music, and voice acting. Role playing titles such as Ys Book I & II showcased the power of this technology, offering cinematic storytelling and soundtracks that felt closer to a film than a game. By the early nineties, Japanese gamers had already embraced the disc format that the rest of the world would not experience widely until the PlayStation era (Wired).

In North America, however, the story was very different. The TurboGrafx-16 was rebranded and marketed aggressively, but it struggled to find its audience. Its launch library was limited, its advertising was confusing, and many of its best titles remained locked in Japan. Competing against both the Sega Genesis and the Super Nintendo proved impossible. While Bonk’s Adventure and Blazing Lazers developed cult followings, the console never reached mainstream success. By the mid-nineties NEC had largely abandoned the American market (GameDeveloper).

Yet the legacy of the TurboGrafx-16 cannot be dismissed. It normalized CDs in gaming years before Sega or Sony committed to the format. It also delivered arcade-quality ports, with games like R-Type and Castlevania: Rondo of Blood proving that home systems could finally match the arcade experience. These achievements set expectations for what future consoles would deliver.

How it helped the industry grow: The TurboGrafx-16 showed that discs were the future of storage, sound, and storytelling. Although it failed in the United States, it proved that gamers wanted deeper experiences, better soundtracks, and bigger worlds. Every time you play a modern game with orchestral music and cinematic cutscenes, you are seeing the influence of NEC’s overlooked little console.

Atari Jaguar

Atari had once been the face of video games, but by the early nineties the company was struggling. In 1993 it unveiled the Jaguar, which was marketed as the world’s first sixty-four-bit console. Advertisements mocked the competition with the slogan “Do the Math.” The truth was more complicated. The system used a Motorola 68000 chip alongside two custom processors called Tom and Jerry. The architecture was powerful but confusing, and developers quickly discovered that it was far more difficult to program for than the Genesis or Super Nintendo (Wikipedia).

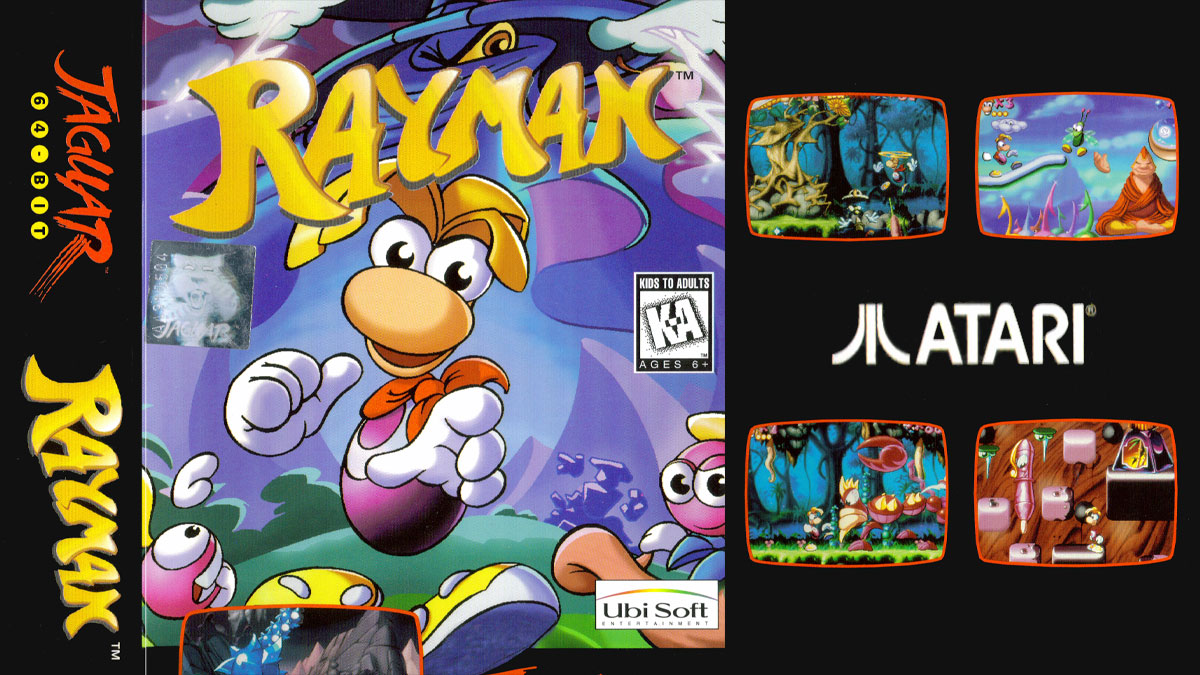

Because of these difficulties, the Jaguar never attracted strong third-party support. Its library was thin, and many of the games it did receive were underwhelming. Yet within that limited selection there were sparks of brilliance. Tempest 2000, designed by Jeff Minter, became a celebrated shooter that is still praised today. Alien vs Predator offered a unique blend of survival horror and first-person shooting, years before those genres merged elsewhere. And perhaps most significant of all, Michel Ancel’s Rayman was born on the Jaguar. The first entry in the franchise appeared on Atari’s troubled machine before being ported to the PlayStation and Saturn. Today Rayman is considered one of the greatest platformers ever made, but its roots trace back to this forgotten system (Reset Era).

Commercially, the Jaguar was a disaster. Only about a quarter of a million units were sold, and by 1996 Atari had stopped producing the hardware. Yet the story took an unusual turn. In 1999 Hasbro Interactive, which then owned Atari’s assets, released the patents for the Jaguar into the public domain. This effectively made the console an open platform. Enthusiasts and hobbyists began creating homebrew titles, and to this day the Jaguar has a small but active development community.

How it helped the industry grow: The Jaguar taught the industry that power alone means nothing without tools that make development accessible. This lesson influenced how Sony built the PlayStation and how Microsoft approached the Xbox. It also gave the world Rayman, a franchise that remains relevant decades later. Finally, by becoming one of the first open platforms, it showed how fan communities could breathe life into hardware long after its commercial death.

3DO Interactive Multiplayer

The 3DO Interactive Multiplayer, released in 1993, was a bold experiment conceived by Trip Hawkins, the founder of Electronic Arts. Unlike Nintendo or Sega, 3DO did not intend to manufacture hardware. Instead it created a design standard and licensed it to companies such as Panasonic and GoldStar, who produced the machines themselves. The idea was to separate the business of making hardware from the business of making software, a model closer to modern smartphones than traditional consoles (YouTube).

The 3DO was technologically advanced. It offered thirty-two-bit processing, CD storage, full-motion video, and audio quality that rivaled home stereos. It was marketed not only as a game system but as a complete multimedia hub. For the first time, the idea of a console as a general entertainment device began to take shape. Games such as The Need for Speed and Road Rash introduced realistic driving physics and licensed soundtracks. Gex became a cheeky mascot platformer that gave the system personality. While many of its full-motion video titles have aged poorly, they reflected an industry eager to experiment with cinematic presentation.

The fatal flaw was price. At launch, the 3DO sold for nearly seven hundred dollars, a figure that placed it well out of reach for most gamers. At the same time, the Sega Genesis and Super Nintendo were far cheaper and had much larger libraries. Within two years the PlayStation and Saturn arrived, both stronger competitors with better support. The 3DO could not survive this onslaught, and by 1996 it had disappeared from store shelves (Black Falcon Games).

How it helped the industry grow: Despite its short life, the 3DO left a lasting mark. It proved that consoles could serve as multimedia centers, paving the way for the DVD functions of the PlayStation 2 and the streaming features of modern systems. It launched The Need for Speed, one of the longest running and most successful racing franchises in history. It also introduced the idea of a standardized hardware platform, a concept that would later resurface in smartphones and virtual reality headsets.

Sega CD

In 1991 Sega released the Mega-CD in Japan, which arrived in North America in 1992 as the Sega CD. Rather than a standalone console, it was an add-on for the Genesis. By attaching a disc drive to the system, players could access a new generation of games and features. At a price of nearly three hundred dollars it was not cheap, but it offered experiences that cartridges could not match. One of its most overlooked features was that it could play audio CDs, making it one of the first game systems that also served as a home stereo (Wikipedia).

The Sega CD’s library was varied. On one end were role playing and adventure games that took full advantage of the disc format. Lunar: The Silver Star delivered an epic story with voiced dialogue and an orchestral score. Snatcher, a cyberpunk adventure created by Hideo Kojima, used its expanded storage for atmospheric storytelling and became a cult classic. On the other end were full-motion video games such as Night Trap and Sewer Shark. These were more like interactive movies than traditional games, and while they were often criticized for shallow gameplay, they represented an industry attempting to blend cinema with interactivity.

The controversy surrounding Night Trap made the Sega CD historically significant. In 1993 the game was singled out in U.S. Senate hearings that debated the influence of violent video games on children. The hearings led directly to the creation of the Entertainment Software Rating Board, which established a rating system that is still used today (Polygon). Although Sega could not have predicted it, the Sega CD played a role in legitimizing gaming as an industry capable of self-regulation.

How it helped the industry grow: The Sega CD demonstrated that consoles could be multimedia devices, not just game machines. It introduced millions of players to CD-quality sound and voice acting, paving the way for the cinematic experiences of later generations. It also triggered the debate that created the ESRB, a system that gave gaming credibility in the eyes of regulators and parents. While it did not succeed commercially, its influence has echoed through every console generation since.

Conclusion

The TurboGrafx-16, the Atari Jaguar, the 3DO, and the Sega CD all struggled to survive in the marketplace. They were too expensive, too complex, or simply unlucky in their timing. Yet to judge them only by their sales is to miss the bigger picture. Each one contributed to the growth of the medium in ways that are easy to overlook but impossible to ignore.

The TurboGrafx-16 proved that discs were the future and gave us arcade-perfect ports long before they were standard. The Atari Jaguar reminded the industry that hardware must be accessible to developers, and in the process it birthed Rayman, one of the greatest platformers of all time. The 3DO showed how consoles could serve as multimedia centers and gave us The Need for Speed, a franchise that continues today. The Sega CD introduced gamers to cinematic storytelling and inadvertently created the ESRB, forever changing how games are regulated.

These machines remind us that gaming history is not a straight line of victories. It is a messy process of trial and error. Sometimes the consoles that fail the hardest are the ones that teach the industry its most important lessons. When you enjoy cinematic cutscenes, orchestral soundtracks, or racing through the streets of a modern Need for Speed, you are benefiting from the risks taken by consoles that most people have forgotten. Their commercial lives may have been short, but their influence endures in every generation that followed.

Retro Replay Retro Replay gaming reviews, news, emulation, geek stuff and more!

Retro Replay Retro Replay gaming reviews, news, emulation, geek stuff and more!