How Two Dudes, a Dream, and a Roguelike Built a Funkadelic Classic

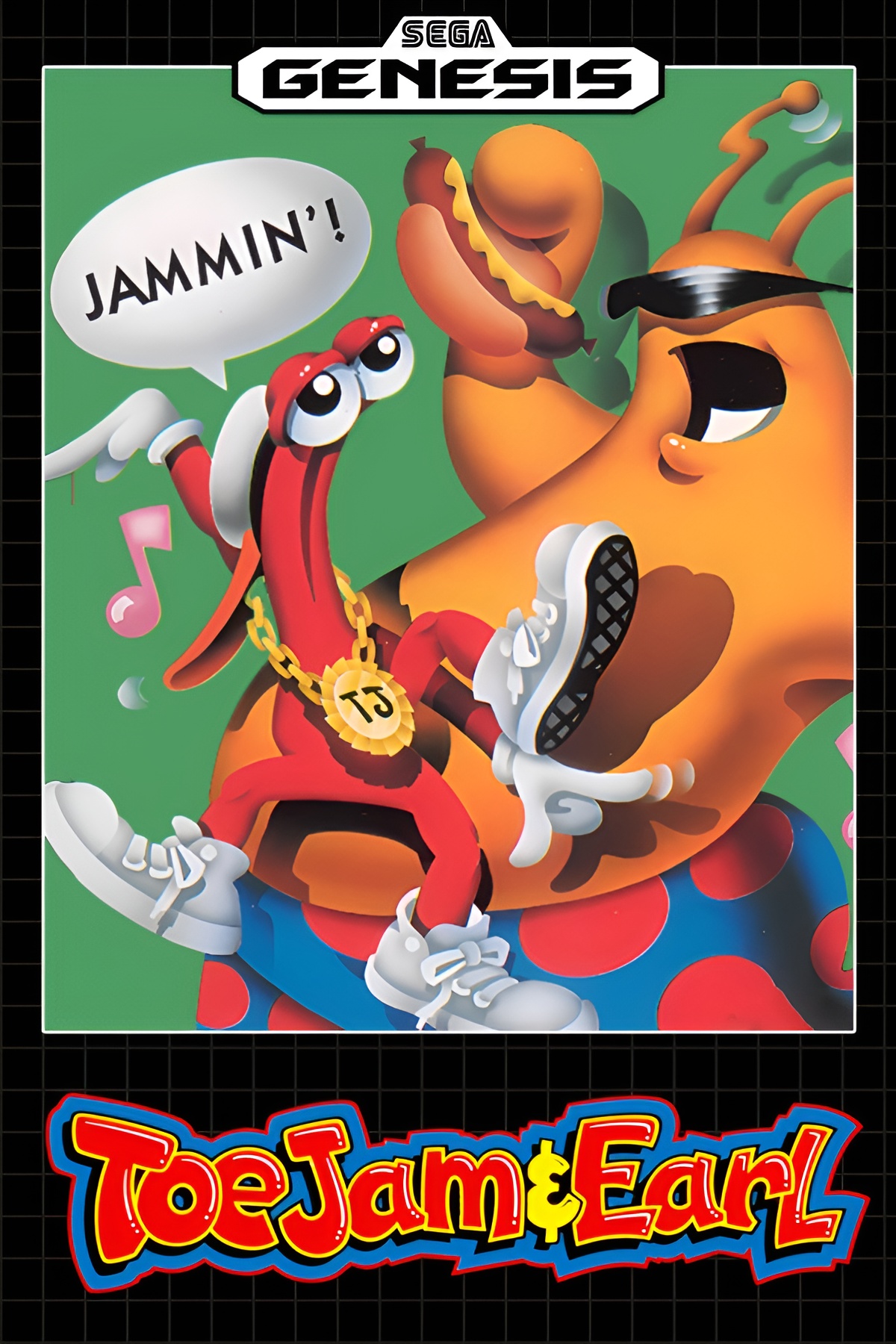

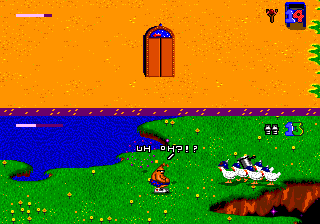

In 1991, the video game console war was defined by one thing: attitude. The Sega Genesis, with its “Blast Processing” and edgy mascot, Sonic the Hedgehog, was in a head-to-head brawl with Nintendo. The landscape was dominated by lightning-fast platformers, brutal brawlers, and arcade-perfect shoot ’em ups. And then… there was ToeJam & Earl.

(HEY YOU!! We hope you enjoy! We try not to run ads. So basically, this is a very expensive hobby running this site. Please consider joining us for updates, forums, and more. Network w/ us to make some cash or friends while retro gaming, and you can win some free retro games for posting. Okay, carry on 👍)

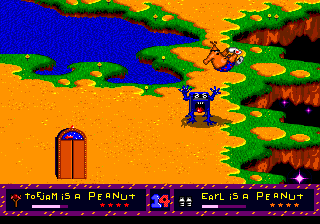

It was a game that wasn’t fast. It wasn’t particularly action-packed. It had no bosses, and the primary goal was to simply… walk around, find presents, and avoid painfully uncool Earthlings. It was slow, weird, satirical, and built on a jazz-funk beat that sounded like nothing else on the console. It was, by all accounts, a commercial risk. It also became one of the most enduring cult classics of the 16-bit generation.

This is the story of how a tiny, two-man team—Greg Johnson and Mark Voorsanger—channeled a bizarre dream, a love for 1980s hip-hop culture, and the DNA of a 1980s mainframe computer game to create a masterpiece of cooperative gaming.

The Dons of Funk: Johnson-Voorsanger Productions

Before there was ToeJam & Earl, there was just Greg Johnson and Mark Voorsanger.

Greg Johnson was the creative mind. He had already made a name for himself in the 1980s game industry. After getting his start in game design, he worked for Electronic Arts, where he was a key designer on the groundbreaking 1986 space exploration game, Starflight [Source: Greg Johnson (game designer) – Wikipedia]. Starflight was a massive, open-ended game of space travel and resource management that itself influenced a generation of developers. Johnson had a proven knack for creating deep, systemic experiences. He was also, by his own admission, not a fan of the gratuitously violent games that were becoming popular [Source: A conversation with Greg Johnson, the creator of ToeJam & Earl – Kill Screen].

Mark Voorsanger was the technical wizard. With a background in electrical engineering and computer science, he had worked on the NEMO project at Hasbro, which was developing full-motion interactive games—a project that would eventually, and infamously, lead to the Sega CD title Night Trap [Source: History of: ToeJam & Earl – Sega-16]. Voorsanger was a programming powerhouse, exactly the kind of technical partner Johnson needed to bring a complex idea to life.

The two were introduced in 1989 by a mutual friend while on a walk. Johnson, fresh off his work on Starflight 2, pitched his “crazy idea for a game” to Voorsanger, who simply replied, “Sure, why not” [Source: Interview: Greg Johnson (Creator of ToeJam & Earl) – Sega-16]. They formed Johnson Voorsanger Productions and got to work, operating as a tiny, two-man garage shop.

The Dream of Funkotron

The concept for ToeJam & Earl didn’t come from a marketing meeting or a trend analysis. It came, quite literally, from a dream.

Greg Johnson had a vivid dream about two quirky aliens crash-landing on a bizarre, floating version of Earth. He woke up, sketched the characters, and wrote down some dialogue [Source: Greg Johnson (SEGA/ToeJam and Earl) – Interview – Arcade Attack]. These initial sketches were ToeJam, a lanky, three-legged red alien with a backwards cap and a gold medallion, and Earl, a portly, sunglasses-wearing orange alien. They were a walking, talking parody of early 90s urban and hip-hop culture, dripping with slang and a “Bill & Ted”-style laid-back vibe.

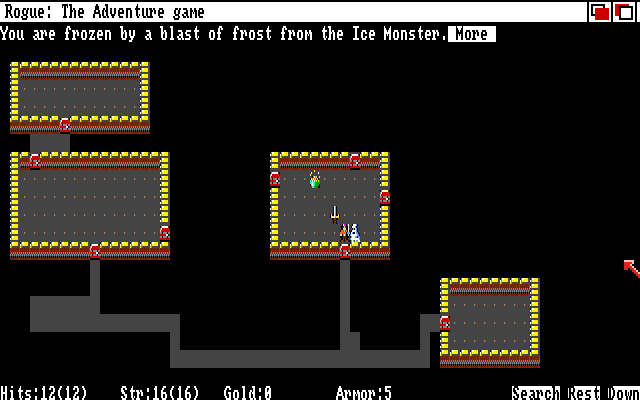

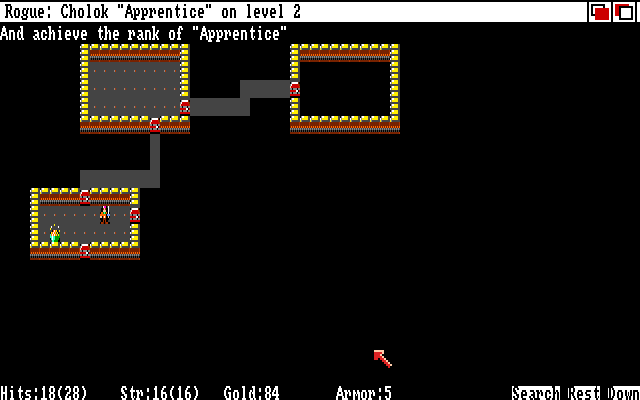

But a cool theme isn’t a game. For the gameplay, Johnson pulled from a deep cut: the 1980 university mainframe game, Rogue.

Rogue was the progenitor of the “roguelike” genre. It featured randomly generated levels, permadeath, and a focus on exploration and item management. Johnson loved Rogue’s core loop: the tension of exploring the unknown, the mystery of unidentified items (potions in Rogue, presents in TJ&E), and the infinite replayability from its random-level generation. In an interview, Johnson stated, “The design of TJ&E was really based on an old favorite game of mine called Rogue. I used to stay up till 4:00 am regularly playing that… The random levels are really an integral part of the game” [Source: Interview: Greg Johnson (Creator of ToeJam & Earl) – Sega-16].

This was the genius of the concept: Johnson fused the hardcore, systemic design of Rogue with a completely accessible, non-violent, and humorous theme. The “potions” became “presents,” which could be good (like Icarus Wings or Rocket Skates) or bad (like “Total Bummer!” or a rain cloud). The “monsters” became a satirical collection of Earth’s worst inhabitants: caffeine-addled dentists, nerdy swarms, phantom ice cream trucks, and the dreaded Boogeyman.

Crucially, Johnson and Voorsanger designed it from the ground up to be a two-player cooperative game. They wanted a game they could play together. This led to the game’s most celebrated feature: the dynamic split-screen. When the two players were close, they shared one screen. When they wandered apart, the screen would seamlessly divide, allowing them to explore independently—a technical marvel for the time.

Pitching the Funk to Sega

With their concept in hand, Johnson and Voorsanger Productions (later renamed ToeJam & Earl Productions, Inc.) [Source: ToeJam & Earl Productions – Wikipedia] went to pitch their game.

Their timing was perfect. In 1989-1990, Sega of America was still the scrappy underdog. They were desperate for innovative, original games and new mascots that could help them build an identity distinct from Nintendo’s family-friendly empire [Source: ToeJam & Earl – Wikipedia].

The duo met with Hugh Bowen, a Sega marketing manager. To demonstrate their Rogue-like random level concept, they brought a stack of 3×5 index cards, each with landscape drawings, and physically laid them out on the floor to show how the levels would be assembled [Source: Greg Johnson (SEGA/ToeJam and Earl) – Interview – Arcade Attack].

Bowen loved the weird, original concept. He brought in producer Scott Berfield to help champion the game internally. Sega’s management greenlit the project, taking a chance on two guys and their funky alien idea. Johnson and Voorsanger were effectively a first-party developer for Sega, which is why the game would remain a Genesis exclusive for decades [Source: Interview: Greg Johnson (SEGA/ToeJam and Earl) – Arcade Attack].

The game was a go. Now, the two-man team just had to build it.

Part 2: The “Garage Shop” and the Friends Who Built Funkotron

When Sega greenlit ToeJam & Earl, Johnson Voorsanger Productions wasn’t a sprawling studio. It was, as Greg Johnson later described it, “just two guys in an office building a game as fast as we could” [Source: Interview: Greg Johnson (Creator of ToeJam & Earl) – Sega-16]. Greg Johnson took on the roles of designer, producer, and primary artist, while Mark Voorsanger single-handedly programmed the entire, complex game.

But they weren’t entirely alone. The game’s credits list a small, tight-knit group of collaborators who were essential in translating the core concept into a living, breathing, and funky world. This small team, combined with “invaluable aid” from other industry pioneers, is what elevated ToeJam & Earl from a clever idea to a masterpiece of 16-bit design.

Finding the “Look”: The Art and Soul of the Aliens

While Greg Johnson was the game’s primary designer and artist, he wasn’t a professionally trained illustrator. His initial sketches, born from his dream, captured the vibe of the characters, but they needed a professional polish to become the icons we know today.

The game’s credits list Greg Johnson and Avril Harrison for “Artwork.” Harrison’s work was crucial in helping build out the game’s world, translating Johnson’s art direction into the vast library of tiles, sprites, and environmental assets that the random level generator used to build its floating islands.

However, the game’s most defining visual element—the characters themselves—came from an uncredited friend. This is one of the most famous “deep cut” facts about the game: the final character designs, the iconic box art, and the quirky illustrations in the game’s manual were all drawn by Steve Purcell [Source: ToeJam & Earl – Wikipedia].

Yes, that Steve Purcell—the artist and animator from LucasArts famous for creating the surreal freelance police duo, Sam & Max.

Purcell’s contribution cannot be overstated. He took Johnson’s concepts and infused them with a professional, comic-book energy. It was Purcell who finalized ToeJam’s lanky, three-legged swagger and Earl’s lovable, blocky frame. His art for the manual, depicting enemies like the “Insane Dentist” and the “Hula Dancers,” was hilarious and perfectly set the game’s satirical tone before you even pressed start [Source: Comic Art Fans – ToeJam & Earl Manual Art by Steve Purcell]. His uncredited work gave the game a visual identity that was leagues beyond what a typical two-man team could produce, making it look and feel like a major, flagship release.

Composing the Funk: The Audio Team

If the art gave the game its look, the music gave it its soul. The ToeJam & Earl soundtrack is legendary. It wasn’t just a collection of catchy chiptunes; it was a deeply complex, bass-driven, generative funk and jazz soundtrack. In an era of high-octane rock anthems, its laid-back, “stroll-through-the-park” vibe was revolutionary.

This auditory masterpiece was the work of three key people:

- John Baker (Music Composition): Baker was the composer responsible for the game’s core tracks. He used the Genesis’s YM2612 sound chip in a way few others did, prioritizing a fat, melodic bassline as the lead instrument for most songs. This is what gave the game its signature “funk” [Source: History of: ToeJam & Earl – Sega-16]. The music was also dynamic, subtly changing as players explored or got into trouble.

- Mark Miller (Music Direction): As Music Director, Miller would have guided the overall sound and implementation of Baker’s compositions, ensuring they fit the game’s pacing and atmosphere.

- Robert Leyland (Sound FX): Leyland, who also contributed programming, created the game’s unforgettable sound effects. From the “Hallelujah” chorus when opening a good present to the “wah-wah-wah” of the Boogeyman, the whoosh of Rocket Skates, and the iconic “Boogeyboogeyboogey!” of the dancing devils, the sounds were the humor.

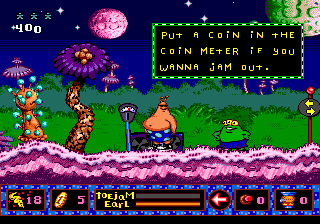

The music was so central to the experience that the game even included a “Jam Session” mode, a simple music generator where players could trigger basslines, drum beats, and sound effects. The team didn’t just make a soundtrack; they made the entire game an interactive musical toy.

The “Invaluable Aid” of Friends

The game’s credits famously give thanks for “Invaluable Aid” to Paul Reiche III and Fred Ford. To 16-bit gaming fans, these names are royalty: they are the co-founders of Toys for Bob and the creators of the Star Control series.

This wasn’t a coincidence. Greg Johnson, Reiche, and Ford were all part of a tight-knit Northern California developer community. Johnson had been an early advisor on Starflight, a game that would directly inspire Reiche and Ford to create Star Control II [Source: Paul Reiche III – Wikipedia]. In turn, Johnson (who is credited for “Additional Design” on Star Control II) received crucial feedback and support from Reiche and Ford during the development of ToeJam & Earl [Source: Fred Ford (programmer) – Wikipedia].

This “invaluable aid” was the collaboration of peers. They were all “indie” developers in spirit, working in small teams to make complex, system-driven games that the big publishers wouldn’t have understood. Reiche and Ford, who were simultaneously building their own complex, alien-filled universe, were the perfect sounding board for Johnson and Voorsanger. They provided critical playtesting, design feedback, and the moral support needed to see such an unorthodox project through to completion.

The Code: A Two-Man Technical Marvel

While the art and sound gave the game its personality, the programming by Mark Voorsanger, with additional help from Robert Leyland, is what made it work. Voorsanger, as the sole lead programmer, pulled off two technical feats that were central to the game’s success.

First was the random level generator. As Johnson noted, the idea was simple (the 3×5 cards), but implementing it on the Genesis was a challenge of memory management. Voorsanger had to create an algorithm that could randomly place landmasses, items, enemies, and spaceship pieces across 25 levels, ensuring each playthrough was unique but also winnable, all while fitting on a small cartridge [Source: Interview: Greg Johnson – Arcade Attack].

Second, and most famously, was the dynamic split-screen. Johnson and Voorsanger were adamant that this be a two-player cooperative game. Sega’s own technical staff reportedly believed a true dynamic split-screen, where the screen would seamlessly divide and rejoin as players moved, wasn’t possible on the Genesis hardware. Voorsanger, through sheer programming skill, made it happen [Source: ToeJam & Earl – Wikipedia]. This single feature defined the game. It allowed for true, independent co-op exploration, creating the classic “Hey, come check this out!” or “Oh no, I found the Boogeyman, run!” moments that players still talk about today.

By 1991, the game was complete. Thanks to a tiny, focused team and a network of talented friends, Johnson Voorsanger Productions had built a game that was technically brilliant, artistically unique, and musically sublime. Now, Sega had to figure out how to sell this bizarre, funky, slow-paced masterpiece to a world obsessed with speed.

The Sleeper Hit and the Panic on Funkotron

In October 1991, ToeJam & Earl landed on store shelves. It was a critical moment. Sega was in the midst of its most aggressive marketing push ever, centered on its new mascot, Sonic the Hedgehog, who had debuted just a few months prior. The market was flooded with titles defined by speed, action, and “Blast Processing.”

ToeJam & Earl was the antithesis of this. Its box art, while brilliant, was also bizarre. Its gameplay was slow-paced. Its premise was, for lack of a better word, weird. Unsurprisingly, the game was not an immediate runaway bestseller.

The Slow Groove to Cult Classic Status

Initial sales were sluggish. [Source: Greg Johnson (game designer) – Wikipedia] Many gamers, conditioned by the arcade action of the day, didn’t know what to make of it. Mean Machines magazine, in its 1991 review, captured this sentiment perfectly: “Not everyone will like it—it’s not normal enough for mass appeal—but I think it’s destined to become a massive cult classic.” [Source: ToeJam & Earl – Wikipedia]

This prediction was astoundingly accurate. ToeJam & Earl became the definition of a “sleeper hit.” Its success wasn’t driven by a massive launch-day marketing budget but by a slow, powerful word-of-mouth campaign.

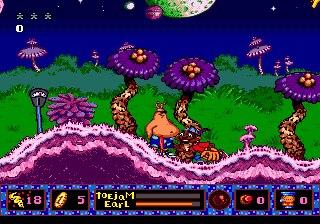

The game’s two-player cooperative mode was its secret weapon. Kids would have sleepovers, and one friend would introduce the game to another. The shared experience—the laughter from a “Randomizer” present backfiring, the shared panic of hearing the Boogeyman’s “wah-wah-wah,” the triumph of finding the last spaceship piece—was infectious. The game was also heavily rented, passing from home to home.

Sega, to its credit, recognized the game’s growing appeal. The characters of ToeJam and Earl began appearing in Sega’s marketing as secondary mascots. They even got their own mini-game, Ready-Aim-Tomatoes, in the 1992 light-gun bundle, the Menacer 6-Game Cartridge. [Source: History of: ToeJam & Earl – Sega-16]

By the end of the Genesis’s life cycle, ToeJam & Earl was no longer an obscure oddity; it was a beloved, system-defining classic. It had built a loyal and passionate fanbase who loved its unique Rogue-like gameplay, its satirical humor, and its laid-back funk. Naturally, this dedicated fanbase was desperate for a sequel that would give them more of exactly that.

They would not get it.

The Sequel Sega Wanted: Panic on Funkotron

Flush with the success of their first game, Greg Johnson and Mark Voorsanger began development on ToeJam & Earl 2. Their initial plan was a direct, “plan A” sequel: a bigger, better version of the original game. They got about three months into development, implementing new features like indoor areas (buildings and caves) and slippery ice levels, all built on the same Rogue-like, randomly-generated, top-down framework. [Source: Interview: Greg Johnson (Creator of ToeJam & Earl) – Sega-16]

Then, Sega stepped in.

By 1993, the console war had only intensified. Sonic the Hedgehog 2 had been a colossal success. The 2D side-scrolling platformer was king, and Sega’s marketing machine was built to sell them. From Sega’s perspective, a slow, top-down exploration game was a “marketing problem.” They couldn’t easily sell it. A colorful side-scroller starring their funky alien mascots? That they could work with.

As Johnson recalled, Sega executives felt a platformer would be more marketable and “couldn’t identify with what had made ToeJam & Earl so special.” [Source: History of: ToeJam & Earl – Sega-16] Fearing their game would be shelved and unsupported, Johnson and Voorsanger made a fateful decision: they scrapped their “plan A” sequel entirely and, from scratch, began building the game Sega wanted.

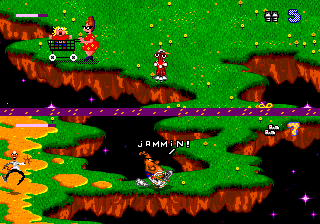

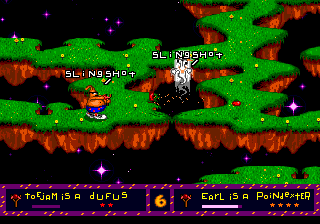

The result, released in 1993, was ToeJam & Earl in Panic on Funkotron.

A Brilliant Game… That Wasn’t a Sequel

Panic on Funkotron was, by almost every objective measure, an excellent 16-bit platformer. The art was stunning, with vibrant, detailed, and non-linear levels depicting the aliens’ home planet. The music was just as funky as the original. The core “collection” premise remained: instead of spaceship pieces, the duo had to find and trap rowdy Earthlings who had stowed away on their ship and were now running amok on Funkotron.

It even kept the co-op focus and the series’ signature humor. Players used “Funk-Scan” to find hidden items and enemies, and they “attacked” by lobbing glass jars to capture the humans. It was quirky, polished, and fun.

For new players who had never touched the original, it was a fantastic, imaginative side-scroller.

For the dedicated fans of the 1991 classic, it was a profound disappointment.

The fanbase was immediately and intensely divided. The entire Rogue-like element—the random levels, the mystery presents, the top-down exploration, the dynamic split-screen—was gone. It had been replaced by the very genre that ToeJam & Earl had been a refreshing escape from.

In a 2005 interview, Greg Johnson looked back on this decision with clear regret: “In retrospect it’s pretty clear that we should have stuck with plan A. I’m sure that even the folks at Sega would say that too.” [Source: Interview: Greg Johnson – Sega-16]

Panic on Funkotron sold well—in fact, it likely sold better at launch than the original did—but it alienated the core fanbase. After two wildly different games, the series’ identity was confused. Johnson Voorsanger Productions (now officially ToeJam & Earl Productions, Inc.) would move on to other projects, including the award-winning children’s CD-ROM Orly’s Draw-A-Story. [Source: ToeJam & Earl Productions – Wikipedia]

The funky duo would go on ice. It would be almost a decade before ToeJam and Earl would be seen again, and their return would once again be complicated by shifting technology and publisher pressures.

The 3D Mission and the Long Road Home

After Panic on Funkotron, the ToeJam & Earl franchise lay dormant for the rest of the 16-bit era. Johnson and Voorsanger had renamed their company ToeJam & Earl Productions, Inc. and found success with other projects, notably 1996’s Orly’s Draw-A-Story for PC. [Source: History of: ToeJam & Earl – Sega-16] But as the video game industry rocketed from 2D to 3D, the funky aliens were left behind.

Sega had moved on to the Saturn, and then to its final, brilliant, and ill-fated console: the Sega Dreamcast. It was on this new platform that the duo would finally get their chance at a comeback, but it would be a development fraught with change, cancellations, and a repeat of past compromises.

The Canceled Dreamcast Project

Development for a third ToeJam & Earl game began in 1999, targeting the Sega Dreamcast. The plan, once again, was to return to the Rogue-like roots of the original. The team at ToeJam & Earl Productions, Inc. started building a true 3D sequel, intended to be published by Sega.

However, the video game landscape had changed dramatically. Sega was in financial trouble. On March 31, 2001, Sega officially discontinued the Dreamcast, exiting the hardware business to become a third-party software publisher.

With the Dreamcast’s demise, the ToeJam & Earl sequel was left without a platform. The project was unceremoniously canceled.

But Sega wasn’t ready to give up on the IP. They saw potential for the franchise on one of the new dominant consoles, and they decided to shift the project to Microsoft’s brand-new Xbox. This platform shift, however, came with significant creative pressures that would, once again, alter the game’s DNA.

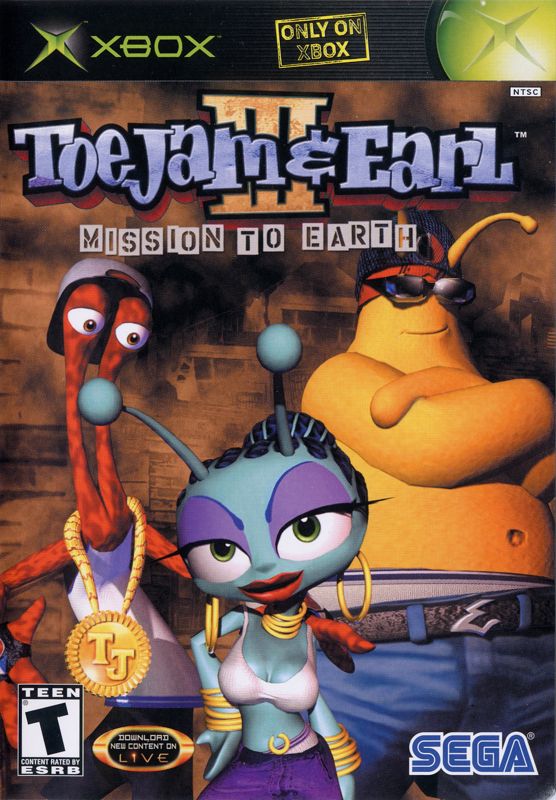

Mission to Earth: The Xbox Compromise

The game was rebooted and re-titled ToeJam & Earl III: Mission to Earth. Released in 2002, it was the first game in the series not developed by the core duo of Johnson and Voorsanger, but rather by Visual Concepts (the studio that would become famous for the NBA 2K series). Greg Johnson was brought on as a lead designer and creative consultant to guide the project, but the publisher and studio now had their own ideas about what a modern 3D game should be. [Source: Greg Johnson (game designer) – Wikipedia]

The result was a game caught between two worlds.

On one hand, Mission to Earth was a clear attempt to return to the original formula. The gameplay was top-down (now in 3D), the levels were randomly generated, and the goal was to explore, find presents, and avoid hostile Earthlings. It brought back the co-op split-screen and the focus on exploration.

On the other hand, it was heavily influenced by the 3D platformer-collectathons of the day, like Banjo-Kazooie or Super Mario 64. Instead of a pure, 25-level climb, the game was structured around a central “hub” world. Players would complete fetch quests and mini-missions to collect keys and unlock new areas. This “hub-and-spoke” design fundamentally changed the game’s flow.

Greg Johnson himself later lamented this compromise. He felt the hub structure “made the random levels much less integral to the game” and that it “really lost some of the addictive nature of the original.” [Source: Interview: Greg Johnson (Creator of ToeJam & Earl) – Sega-16]

The game also introduced a new third character, Latisha, a decision pushed by the publisher to broaden the game’s appeal. While a fun character in her own right, her inclusion further signaled that this wasn’t the pure sequel fans had been waiting for.

ToeJam & Earl III received mixed reviews. Critics and players found it charming but repetitive. The 3D camera was clunky, and the mission-based structure felt dated compared to its contemporaries. The game failed to find a large audience on the Xbox, and its poor commercial performance effectively killed the franchise for a second time.

The Intermission and HumaNature Studios

Following the release of ToeJam & Earl III in 2002 (and its 2003 port), the original creative partnership dissolved. Mark Voorsanger left the game industry around 2005 to become a business consultant. [Source: Greg Johnson (game designer) – Wikipedia]

Greg Johnson, however, continued to design. He worked as a consultant on major titles like The Sims 2 and Spore, where he helped Will Wright make the characters feel more believable. [Source: Greg Johnson – MobyGames] In 2006, he founded his own, new independent studio: HumaNature Studios.

For years, HumaNature Studios worked on other original projects, like the charming Doki-Doki Universe for the PlayStation 4. Johnson seemed to have moved on.

But the fans had not.

Through the 2000s and early 2010s, the original ToeJam & Earl had been re-released on platforms like the Nintendo Wii Virtual Console and the Sega Genesis Collection, introducing it to a new generation. The nostalgia and love for the 1991 classic only grew stronger. The fan community, now connected by the internet, was vocal: they still wanted the true sequel they were denied back in 1993.

In 2014, the “indie” game renaissance was in full swing, and a new platform was giving developers a way to bypass publishers entirely: Kickstarter. Greg Johnson, now in full control of his own studio, saw an opportunity. He decided it was finally time to make “Plan A.”

Back in the Groove and the Timeless Legacy of Funk

After the commercial disappointment of ToeJam & Earl III, the franchise was dead. Greg Johnson had moved on, founding HumaNature Studios and working on new, original IPs. The rights to ToeJam & Earl were a tangled mess, partially held by Sega and partially by Johnson and Voorsanger. For over a decade, the series existed only as a beloved memory and a re-released ROM on various Sega collections.

But the fans never forgot. And in 2015, a new movement in the game industry gave them a voice—and a wallet.

The Funk Is Back (By Popular Demand)

In February 2015, Greg Johnson and HumaNature Studios launched a Kickstarter campaign for a new game: ToeJam & Earl: Back in the Groove.

The pitch was not for a reboot, a reimagining, or a 3D adventure. The pitch, at long last, was for “Plan A.” It was a direct, unapologetic promise to create the true sequel to the 1991 original, bypassing publisher meddling entirely.

The Kickstarter page was a direct appeal to the fans who had been disappointed by Panic on Funkotron and Mission to Earth. It promised a return to the classic formula:

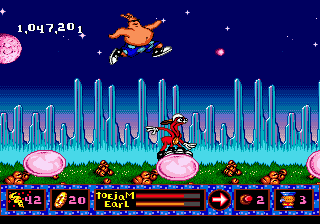

- Top-down, 2.5D fixed-perspective gameplay.

- Randomly-generated, stacked, floating levels.

- A hunt for spaceship pieces.

- Mystery presents (both good and bad).

- Classic Earthling enemies.

- A heavy emphasis on 4-player co-op, now with online support.

- And, crucially, a new soundtrack by John Baker, the composer from the original 1991 game.

The response was immediate and overwhelming. The community that had been quietly waiting for 24 years showed up in force. The campaign blew past its $400,000 goal, ultimately raising over $508,000 from nearly 9,000 fans. [Source: ToeJam & Earl: Back in the Groove! Kickstarter] This wasn’t just funding for a game; it was a mandate. The fans weren’t just buying a product; they were paying to have a 24-year-old design promise fulfilled.

Development and Release: The True Successor

Freed from the market pressures of a major publisher, Greg Johnson and his small team at HumaNature Studios spent the next four years building the game their fans (and they) had always wanted. The development was public, with Johnson frequently engaging with the community and sharing progress.

ToeJam & Earl: Back in the Groove was finally released on March 1, 2019, for PC, Nintendo Switch, PlayStation 4, and Xbox One.

The game was, in every conceivable way, the sequel to the 1991 original. It felt less like a modern game and more like a beautifully restored classic that had been discovered in a time capsule. While it featured a new 2.5D art style that lovingly recreated Steve Purcell’s original character designs, the gameplay was pure 1991. [Source: ToeJam & Earl – DJMMT’s Gaming Blog]

It had the slow-paced exploration, the panic-inducing Earthlings, the joy of finding Icarus Wings, and the agony of opening a “Total Bummer!” present. It was, as one reviewer noted, “one of the most true-to-form remakes” ever made. [Source: DJMMT’s Gaming Blog]

The reception was a mirror image of the series’ past. While some modern critics who were new to the series found its gameplay loop simple or slow (the same “criticisms” the original faced), the fans adored it. It was vindication. It proved that the original Rogue-like formula was timeless and didn’t need a 3D overhaul or a platformer spin-off to be fun.

The Legacy of Two Funky Aliens

The story of ToeJam & Earl is more than just the history of a quirky game. It’s a decades-long case study in creative vision, publisher conflict, and the enduring power of a loyal fanbase.

- A Pioneer of the “Console Rogue-lite”: Years before “roguelike” or “roguelite” became mainstream indie genres, ToeJam & Earl successfully translated the hardcore, complex, and random-level design of Rogue into an accessible, non-violent, and hilarious console experience. It was a pioneer of systemic, emergent gameplay, where a simple set of rules (presents, enemies, random levels) could create nearly infinite stories.

- The Gold Standard of Co-op: The game remains one of the most beloved cooperative experiences in history. The dynamic split-screen (a technical marvel by Mark Voorsanger) was a design masterpiece that allowed for true, shared exploration, creating a social experience that few games, even today, have managed to replicate.

- A Time Capsule of Perfect Satire: The game’s theme wasn’t just a gimmick. It was a sharp, funny, and surprisingly gentle satire of Earthly life, as seen through the eyes of two laid-back outsiders. [Source: A conversation with Greg Johnson, the creator of ToeJam & Earl – Kill Screen] It captured the specific “Bill & Ted” vibe and burgeoning hip-hop culture of the early 90s, set to a flawless funk soundtrack that defined “cool” for a generation of 16-bit gamers.

The franchise’s history is one of starts and stops. The brilliant original, the compromised side-scroller, the canceled Dreamcast project, the compromised 3D sequel, and finally, the fan-funded return. The journey of Greg Johnson and Mark Voorsanger, from two guys in an office to the custodians of a cult classic, shows the struggle of maintaining a unique creative voice.

The ultimate success of Back in the Groove proved what the fans had known all along: the original formula was never broken. It didn’t need fixing. It was just waiting, patiently, for the rest of the world to get back on the beat.

Retro Replay Retro Replay gaming reviews, news, emulation, geek stuff and more!

Retro Replay Retro Replay gaming reviews, news, emulation, geek stuff and more!

My all-time favorite franchise. The second game is my all-time favorite