A Forgotten Genesis Oddity

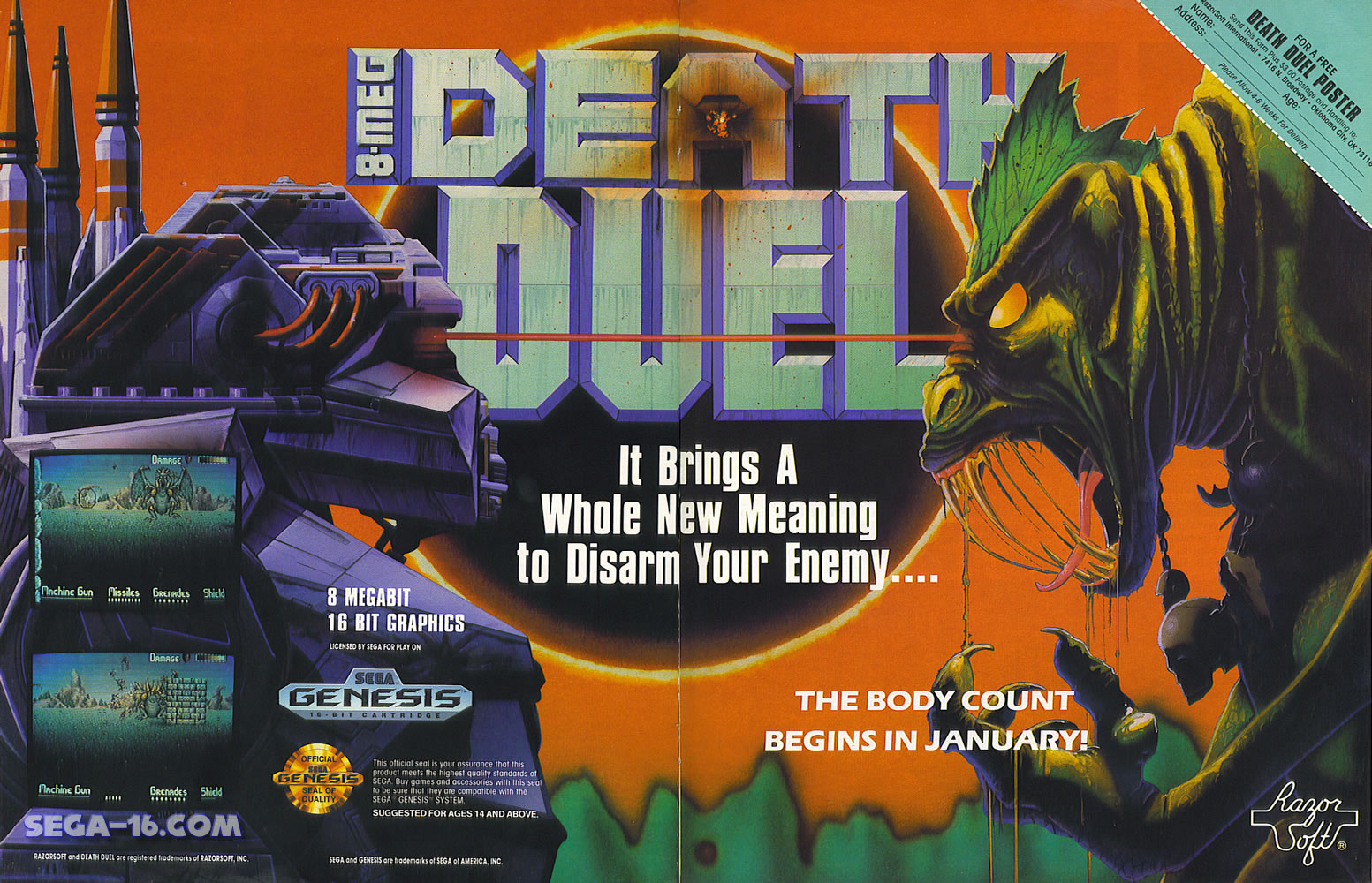

There are some Genesis games you remember the instant you hear their names. Sonic spins into view, Streets of Rage echoes with its iconic soundtrack, and Golden Axe still makes you feel like you are clutching an arcade joystick in a smoky pizza parlor. Then there are the other cartridges, the ones that did not get their own TV commercials or full-page spreads in Electronic Gaming Monthly, but instead whispered their way into the rental shops with a strange energy. Death Duel, released in 1992, was one of those cartridges. It was not colorful, it was not friendly, and it certainly was not aimed at little brothers and sisters. It was the kind of game you rented late on a Friday night, drawn to the cover art that showed a hulking mech straight out of a heavy metal album jacket, daring you to see what was inside.

(HEY YOU!! We hope you enjoy! We try not to run ads. So basically, this is a very expensive hobby running this site. Please consider joining us for updates, forums, and more. Network w/ us to make some cash or friends while retro gaming, and you can win some free retro games for posting. Okay, carry on 👍)

Part of what made Death Duel so memorable was its mood. Unlike most Genesis titles that invited you into a world of adventure or speed, this one felt mean. Every battle was presented as a grim, first-person showdown, as if you were staring through the cockpit glass of a war machine on some lawless frontier. Instead of exploring stages or rescuing damsels, you were locked into duels against grotesque, biomechanical monstrosities with names like “Mantis” or “Arachnid.” Time was limited, ammunition cost money, and every duel felt like a test of whether you had chosen wisely in the hangar before stepping into combat. That harsh, unforgiving rhythm left an impression. I reviewed this game a while back, and then back even farther.

It was also a product of who made it. The publisher, RazorSoft, was already known for putting out Genesis titles that were rough around the edges but deliberately more adult. They had shipped Technocop and Stormlord, both of which carried reputations for violence and nudity that raised eyebrows in the pre-ratings era Sega Retro. The developer credited here was Punk Development, a small California studio that included names like Jeff Spangenberg, who would later go on to found Iguana Entertainment and, eventually, Retro Studios of Metroid Prime fame MobyGames. Even if Death Duel was never destined to be a blockbuster, the pedigree behind it makes it one of those fascinating footnotes in the Genesis story — a weird, moody, one-on-one mech shooter that felt too strange to ignore.

Who Made Death Duel: RazorSoft and Punk Development

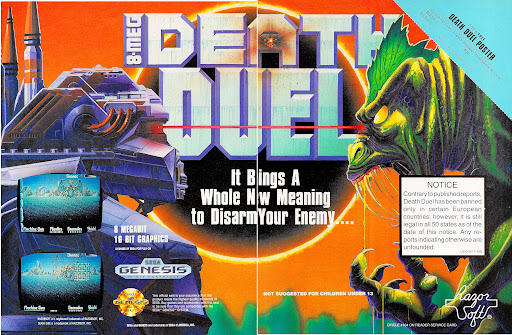

Back in the early nineties RazorSoft was not a name that carried the shine of Sega or Capcom, but if you rented games often enough you knew their logo. They were the small Oklahoma City publisher that delighted in putting out the oddballs. Technocop sprayed pixel blood across the screen, Stormlord caused controversy over its topless fairies, and RazorSoft seemed to enjoy the fact that parents frowned whenever their name came up. They wanted to be the publisher that pushed the Genesis into places Nintendo would never touch, and in that role they earned a reputation as troublemakers. You can still trace their history through Sega Retro’s archive, which catalogues their short but noisy run on Sega hardware.

RazorSoft did not make Death Duel alone. To actually build games they bankrolled a development arm in California called Punk Development, a name that sounded like it came straight out of a garage band flyer. Founded in 1990 by Jeff Spangenberg, Punk set up shop in Sunnyvale and Mountain View. Spangenberg was restless and ambitious, and he surrounded himself with people who were equally scrappy. Kevin Seghetti, one of the early programmers, later remembered how they cobbled together Genesis development tools, emulators, and sound drivers at a time when official kits were hard to come by. He laughed in an interview at GDRI about a development board that came with a bright red solder mask simply because someone thought it looked cool. That was the spirit of Punk, a mix of professionalism and mischief that bled into the games they produced.

When you look at the Death Duel credits you see a tiny team that wore many hats. The roster included programmers Darrin Stubbington, John Cumming, David O’Connor, and Jeff Spangenberg himself. Graphics and music came from Matt Stubbington, and the strange backstory and structure of the game is credited to Kyle Shelley. The Mobygames entry confirms fourteen people in total, which feels almost quaint compared to the hundreds listed in modern titles. But it also explains the peculiar feel of the game. With a team that small, every person’s taste mattered, and what came out of their combined effort was a duel based sci fi world that looked unlike anything else on the system.

Spangenberg’s story did not end there. After RazorSoft’s relationship with Sega soured, he left Punk Development and founded Iguana Entertainment. That studio would become famous for Turok: Dinosaur Hunter on the Nintendo 64, and later Spangenberg would launch Retro Studios in Texas, which went on to create Metroid Prime. To think that the same man who once shipped Death Duel with RazorSoft would later be running a Nintendo backed team is the kind of twist that makes retro gaming history so much fun. Polygon’s feature on the early days of Retro Studios even traces those roots back to the scrappy culture of Punk Development. In that sense Death Duel is more than a forgotten mech game, it is a snapshot of where some of the industry’s future talent was cutting their teeth.

He also founded Topheavy Studios in the early 2000s. That studio is best remembered, or perhaps notorious, for producing The Guy Game in 2004, an Xbox and PlayStation 2 title that drew headlines not for its gameplay but for featuring real-world footage of women, some underage, flashing on camera. The game was pulled from shelves almost immediately after release, cementing it as one of the most infamous titles in gaming history. For anyone looking back at Spangenberg’s career, it is a jarring reminder of how the same creative force who once gave Sega fans the grim duels of 2140 also later made headlines for one of gaming’s most controversial scandals.

The Legal and Business Climate Around Genesis Third Parties

If you were a teenager in 1992, all you probably cared about was whether the cartridge in your hand worked when you shoved it into the slot of your Genesis. But behind the scenes Sega was running a tight ship. Unlike Nintendo, which famously locked down the NES with proprietary chips and iron clad contracts, Sega played a more complicated game. They wanted third party publishers on board, but they also wanted to make sure every cartridge went through them. That meant licensing fees, cartridge manufacturing handled by Sega, and legal agreements that kept everyone in line.

RazorSoft was not the kind of company to play by all the rules. In 1991 Sega filed a lawsuit against RazorSoft and Punk Development, accusing them of breaching contracts, misusing Sega’s trademarks, and even producing their own cartridges instead of going through official channels. The details are preserved in corporate records and have been summarized by researchers at GDRI. Kevin Seghetti, who worked with Punk, later explained that the tension came from RazorSoft wanting more control over its product line and bristling at Sega’s restrictions. For a small publisher built on edgy content, it was not surprising that they would also push against business constraints.

That lawsuit cast a shadow over Punk Development and RazorSoft, but it also explains why their games felt different. When you are operating on the margins, you take creative risks. Sega might have wanted glossy mascot platformers to compete with Nintendo, but RazorSoft was funding dueling mechs and grotesque aliens. Their catalog became a kind of unofficial statement that the Genesis was a system where you could find things Nintendo would never touch. In that sense the lawsuit and the friction with Sega were part of the DNA of Death Duel. Without that rebellious streak, it is hard to imagine a publisher greenlighting a game about mercenary pilots blasting limbs off of biomechanical nightmares in one on one timed battles.

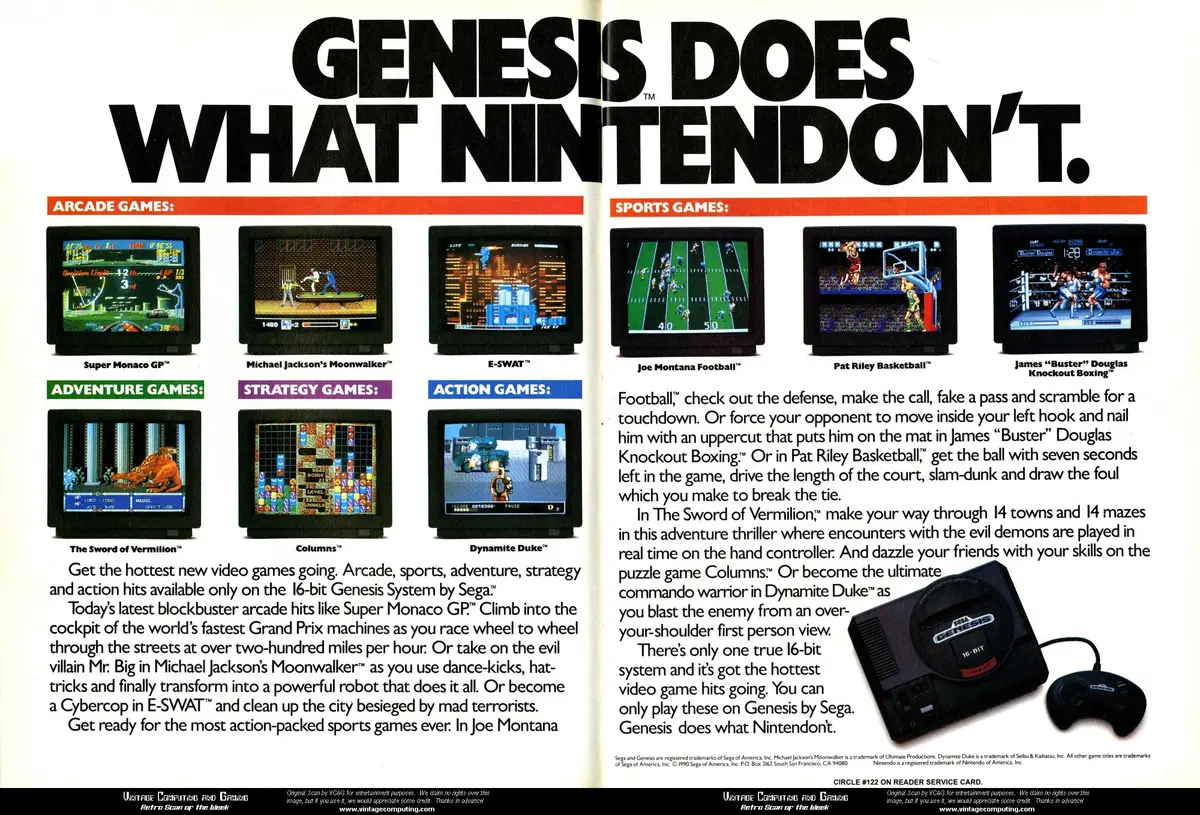

The irony is that even as Sega was taking RazorSoft to court, they were also leaning into the Genesis image of being the system for older kids and teenagers. Their “Genesis does what Nintendon’t” campaign sold attitude as much as hardware, and games like Death Duel actually helped make that pitch convincing. Sega would eventually formalize its control through the Videogame Rating Council in 1993, but Death Duel slipped in just before that, carrying only a vague warning for parents rather than an official age rating. Looking back, the whole thing feels like a snapshot of a lawless moment, when small publishers could still sneak edgy experiments onto the shelves before the industry settled into the guardrails of ratings boards and stricter licensing.

The World of Death Duel: Lore and Storytelling

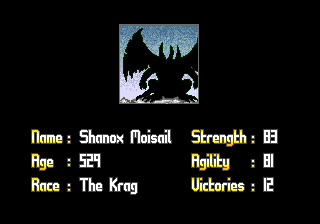

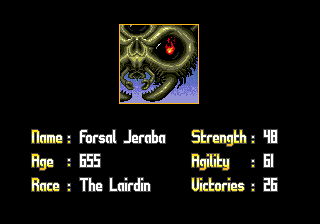

One of the most rewarding parts of revisiting old Genesis cartridges is finding a manual that does more than list controls. Many games of the era gave you a few paragraphs and some diagrams, but Death Duel came with a booklet that poured on the fiction. According to the manual, the year is 2140 and the galaxy has abandoned diplomacy and large scale wars in favor of single sanctioned fights. These duels are not sport, they are binding law. Every planet and every faction accepts the outcome. If you win, your people prosper. If you lose, your colony is forced into subservience. Into this grim framework steps Barrett Jade, a lone human pilot who carries the responsibility of defending Earth’s rights to vital space lanes. He is not a cartoon mascot. He is a mercenary standing at the edge of extinction with nothing but his mech and his nerve. The manual preserved at Sega Retro makes this crystal clear in its opening pages, and the tone feels closer to a graphic novel than a typical video game insert.

What made the premise stand out even more were the enemies themselves. Barrett Jade is tasked with taking down the Super Nine, a league of grotesque alien warlords each with their own style, anatomy, and weak points. They are not generic fodder. Each has a name and a design that makes them feel like unique characters in a twisted science fiction universe. Arachnid is a spider like monstrosity that looms over the battlefield with flailing limbs. Mantis is sharp and angular, its body a hybrid of insect and armor. Slugg is a lumbering beast with armored plates that deflect shots until you learn its vulnerable points. These names and images gave the game a memorable roster that rivaled any fighting game cast of the period. Instead of choosing your own fighter, you studied your opponent and hoped you had chosen the right weapons in advance.

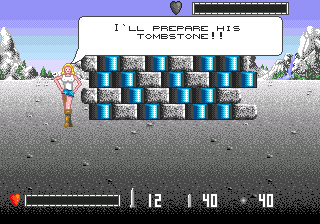

Even before the action began, the game made sure you understood the stakes. Each battle opened with the holographic hostess Reegus, who delivered introductions and biting one liners. She was not there for children. Her attitude was playful but edged with menace, as if she were announcing a deadly underground sport. For players in the early nineties this added an unusual layer of maturity. The Genesis had built its reputation on being cooler and more grown up than Nintendo, and Reegus was a perfect embodiment of that image. She was as much part of the show as Barrett Jade himself, and her presence gave the game a theatrical rhythm that stuck in memory.

Reviewers at the time noticed this atmosphere even if they were lukewarm on the mechanics. Ken Horowitz at Sega 16 wrote a retrospective decades later and gave the game a 7 out of 10. That score speaks volumes. He admitted that the mechanics could be repetitive but praised the unusual presentation and the way the game committed to its dark science fiction world. In his words, it may not have matched the polish of Sega’s best efforts, but it stood apart as something only RazorSoft would dare to publish. That verdict has held steady over time. For many collectors and players who stumbled onto it at a rental shop, Death Duel remains a strange and striking Genesis curio that carved out its own small but loyal audience Sega 16.

The lore is what allows Death Duel to linger in memory long after most one off Genesis titles faded away. By giving the player a name, a role, and a galactic context, Punk Development elevated what could have been a simple series of boss fights into a strange interstellar ritual. For anyone who flipped through the manual before sliding the cartridge in, it felt like opening the first chapter of a comic book you were not supposed to be reading. That sense of forbidden atmosphere is the very thing that gave the game its cult following and still makes it worth discussing all these years later.

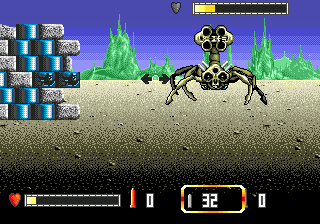

How It Plays: First Person Dueling, Weapons, and Weak Points

The moment you power on Death Duel, you are pushed into a cockpit and told to survive. There is no world map to wander, no platforming warm up to loosen your fingers. You face a single towering opponent across an enclosed arena and the screen begins to glide left and right like a slow conveyor. Your reticle is your lifeline. It doubles as both movement and aim, which means you are constantly deciding whether to strafe or to take a careful shot. That strange tension defines the game. It feels like a grimmer cousin to the rail shooters and gallery blasters that ruled arcades, but here the pace is heavier and the stakes are crueler. Hardcore Gaming 101 summed up the hook in one sharp line, calling it RazorSoft’s only true original and an idea that is “hardly the perfect swan song,” yet still “an interesting idea” for a publisher better known for ports and provocation, a verdict that captures the game’s offbeat pull in a single breath (Hardcore Gaming 101).

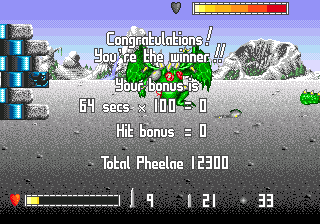

Once the duel begins, the rules are simple and punishing. Ammunition is finite, time ticks down, and your enemy does not go down just because you poured lead into their chest. The manual hints at it, and the game makes sure you learn it the hard way. The fastest way to win is to dismantle the foe. A leg shot stops a charge, a broken weapon silences a rocket rack, and a few surgical hits to the head or core end the fight. The tactical layer is not immediately obvious, but it reveals itself as you pick apart the Super Nine. Classic Games net captures this discovery well, noting the tactical element that slowly emerges once you realize how different each alien behaves, and how learning those quirks is the thin line between a clean victory and a loss on the clock (Classic Games).

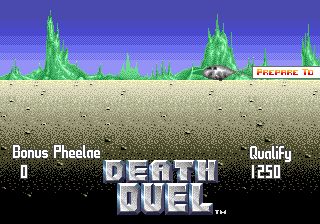

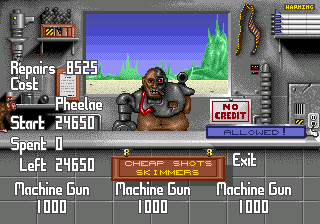

Between duels the tone shifts into a tense routine. A shooting gallery spits out targets and the quick shots you land translate into precious credits. Those credits, called Phaelee in some translations, fund your repairs and your next loadout. You stand in a seedy shop that looks like a back alley armory, reading snarky signs and counting coins before the next appointment with pain. The weapon wall is full of temptations. You can buy cheap machine gun ammo and hope your aim can carry you, or you can blow your budget on a handful of homing missiles and pray every shot lands. Hardcore Gaming 101 points out the issues here with admirable bluntness, especially that “weapon balance is a little skewed,” and that certain tools are situational to the point of feeling like traps for the unwary buyer.

The most memorable truth you learn, often at great expense, is that not every loadout is equal for every duel. Some aliens shrug off lasers and melt under skimmers. Others stumble when their knees go first but become worse nightmares if you do not silence their guns. One reviewer who played it back in 2003 remembered the learning process with gallows humor and a smile. On GameFAQs, DaltonOfZeal wrote, “Ever wanted to blow off a dragon’s head with balled up trash? Here’s your chance,” before praising the oddball Skimmer, a rapid weapon that feels like a heap of compressed garbage yet tears through soft targets when you aim it right. He also flags two truths that every player eventually learns, that the two mode crosshair takes time to master, and that running out of ammo is a fail state that sends you back to square one, which makes planning your three weapon slots less a luxury and more a survival skill (GameFAQs review by DaltonOfZeal).

Cover changes everything. The arenas are littered with barricades that help and hinder in equal measure. In a good run you will duck behind a slab to let a missile scream past while you line up a crippling shot. In a bad run you will watch an almost dead opponent tuck behind the same slab while the seconds evaporate. Classic Games net calls this out as one of the game’s most maddening habits, a behavior that can turn a sure win into a timeout that drains a life and a bank account. The complaint feels familiar to anyone who rented the cartridge and learned to groan when a half ruined monster slid just out of view to stall the clock in silence (Classic Games).

Even the way your guns fire affects your planning. The left and right cannons arc their shots across the screen from their respective sides, while the center cannon shoots straight down the lane. On paper that sounds simple. In practice it means you will sometimes watch an expensive shell smack into a wall because you forgot the arc would clip the barricade in front of you. That small layer of physics minded thinking gives the duels a distinct flavor. It is not just aim and shoot. It is picking the moment, picking the lane, and picking the limb. Hardcore Gaming 101 underlines the design choice to force dismemberment rather than simple damage sponges, a decision that pushes you to play like a surgeon with a shotgun instead of a spray and pray tourist.

All of this creates a loop that feels harsher than most Genesis action games. You fight, you scrape together money, you make a bet on weapons, and you pray that your knowledge of the next opponent is enough to carry you. Campy details lighten the mood only a little. The shopkeeper looks like a half man half machine troll out of a late night cable movie, the bonus stages cough up just enough cash to tempt you into bad purchases, and the announcer Reegus flirts with the camera before each duel as if the whole thing were a cruel television show. The result is a rhythm that sits somewhere between a fighter and a shooter, a ritual of small decisions that slowly teach you how each alien thinks. You can feel why reviewers who stuck with it tend to land on the same conclusion. It can be rough, it can be crude, but once the systems click, the act of dismantling a giant biomechanical nightmare piece by piece is unforgettable.

Art and Sound: Giant Sprites, Juvenile Edge, and Late Night Energy

Death Duel wanted to look and feel like a game for older players, and it wore that identity proudly. From the moment you loaded it up, you were looking out through a cockpit window at an alien monstrosity, locked into a barren arena with nowhere to run. On paper the duels were supposed to feel like titanic clashes, but as Hardcore Gaming 101 pointed out, “the enemy sprites are rather small for the massive creatures they’re supposed to represent,” which left some battles feeling emptier than the premise deserved. Still, the ability to literally dismember foes piece by piece gave the action a raw edge. When an arm burst off in sparks or a leg collapsed in a spray of blood, it gave the illusion of scale that the smaller sprites could not. (Hardcore Gaming 101)

The presentation leaned heavily into shock value. Before each battle, the announcer Reegus appeared with sly commentary and a revealing outfit that seemed designed to scandalize parents rather than impress players. Hardcore Gaming 101 compared the whole style to something “leaped straight from the notebooks of a dozen bored teenagers,” with more gore and sexuality than most console titles of the time. Classic Games net remembered that the advertising even claimed the game was “banned in certain countries,” whether true or not, and that this kind of crude marketing stirred curiosity in rental shops. For a generation of Genesis kids, that was exactly the kind of forbidden energy that made the cartridge irresistible. (Classic Games)

The most infamous moment came after defeat. If Barrett Jade fell in battle, the Grim Reaper would appear, followed by a brutal text scroll that scolded you as a disgrace and warned that your failure had doomed your people. Hardcore Gaming 101 called it “a text scroll so harsh it rivals the AVGN’s profane take” on classic game overs, and even now many remember losing as more memorable than winning. By contrast, the victory ending was anticlimactic, showing a topless woman promising a sequel that never arrived. The imbalance between a vivid defeat and a flat triumph summed up Death Duel’s tone perfectly.

Sound design fared no better. There was no music during the duels themselves, only a pulsing mechanical beat that quickened as your mech took damage. DaltonOfZeal on GameFAQs recalled it as “a sound that somewhat resembles a heartbeat,” noting how little else stood out from the soundtrack. The shop and menus had crude jingles, but nothing that could compete with the rich scores of Streets of Rage or Thunder Force. The visuals outside of battle sometimes had more personality than the duels themselves. The weapon shop in particular, with its grotesque clerk and his pet monkey, gave the game a memorable face that players often remember more clearly than any arena. DaltonOfZeal admitted the designs were “easy to see” and unique enough, but also criticized the lack of polish compared to the system’s best. (GameFAQs review)

Looking back, the art and sound of Death Duel were never about refinement. They were about attitude. RazorSoft and Punk Development leaned into gore, crude humor, and bleak silence to create a game that felt like a VHS rental from the wrong section of the store. It was juvenile, it was sloppy, but it carried a kind of late night energy that stuck in the minds of those who played it.

Rarity, Collecting, and Today’s Price Reality

Back in 1992 Death Duel was never the kind of game most kids begged for at Christmas. It was a curiosity you stumbled across at the rental shop, tucked between more familiar names. That low profile means the print run was modest, and today collectors often describe it as one of the stranger titles to track down for a complete Genesis shelf. It is not impossibly rare, but it has a cult aura, the sort of game that makes visitors pause when they see it displayed next to the system’s classics.

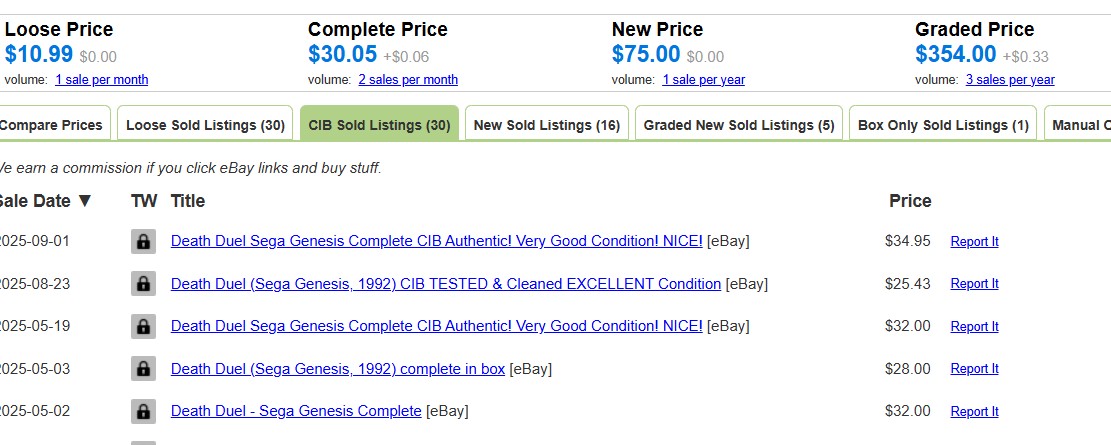

PriceCharting shows exactly where the market has settled. Over the past year, complete in box copies have sold steadily between twenty and thirty five dollars, with the most recent September 2025 sales landing at $34.95 and $25.43 depending on condition. Earlier in the summer, June and July auctions consistently closed just under thirty dollars, while a handful of outliers crept over forty. Loose cartridges generally go for less, but what collectors really want is the full package — the clamshell, the manual, and the cartridge all together. Those manuals in particular are surprisingly tricky to find in good shape, since many kids flipped through them obsessively for the artwork and the lore. (PriceCharting)

What makes Death Duel stand out in a collection is not just the price but the story it carries. This was RazorSoft’s final original title before they folded, which makes it a bookend for the publisher’s short and controversial life. Collectors often note that it represents a whole philosophy of Genesis publishing, one where a company leaned into violence, sexuality, and edginess in an era before content ratings. Retro gamers who hunt for it today are usually chasing more than gameplay. They want the artifact itself, a slice of early nineties gaming culture when rumors of bans overseas and racy endings gave cartridges an aura of danger.

Influence, Comparisons, and the Road Not Taken

Looking back at Death Duel from today, it is tempting to see it as the start of something bigger. The idea of one on one dueling mechs in a cockpit view feels like it could have been the seed for a whole genre on consoles. Yet the truth is that Death Duel did not spark a movement. It remained a strange one-off, a game that stood out in the Genesis library but left little immediate trace in the years that followed.

Still, the DNA of Death Duel can be felt when you line it up against other experiments of the era. Its emphasis on dismantling enemies limb by limb foreshadowed mechanics that later appeared in games like MechWarrior 2, where targeting specific systems was a key to victory. Its first person dueling view feels like a crude cousin of Metal Combat: Falcon’s Revenge on the Super Nintendo, which took the same idea of cockpit based one on one fights but polished it into something more arcade friendly.

The real legacy of Death Duel lies not in sequels but in the people who built it. Punk Development’s roster included Jeff Spangenberg, who went on to found Iguana Entertainment and later Retro Studios. Iguana became known for Turok: Dinosaur Hunter on the Nintendo 64, a landmark in bringing shooters to consoles. Retro Studios, with Nintendo’s backing, created Metroid Prime, which redefined first person adventure. When you trace that path back, you find yourself staring at Death Duel, a scrappy Genesis cartridge where Spangenberg and his team were already experimenting with immersion, cockpit views, and a sense of weighty combat. It is not a direct line, but the spirit of tinkering that Punk Development poured into Death Duel foreshadowed what would come later.

RazorSoft folded, Punk Development faded, and the Genesis moved on to brighter stars. Had the game been more successful, perhaps it could have grown into a small series of dueling mech titles that carved a niche alongside Sega’s fighters and shooters. Instead, it was left alone, a single cartridge that remains a cult favorite. In that sense, its influence is not measured in direct sequels but in the way it reminded players that the Genesis library had room for experiments, failures, and forgotten gems that carried ideas larger than their execution.

Most importantly, it stands as a reminder that the Genesis was not just about blue hedgehogs and arcade brawlers. It was also about oddities like Death Duel, games that dared to be strange, daring, and a little uncomfortable. It may never have shaped the industry, but it carved out its own cult space, and three decades later it still earns a nod of respect from those who remember finding it in the shadows of the Sega library.

As we close the book on Death Duel, this marks the third entry in our ongoing “History of” series, where we revisit forgotten and beloved classics with the care they deserve. If you enjoyed this deep dive into RazorSoft’s cult mech oddity, make sure to also explore our earlier features: the complete bloody saga of Splatterhouse and the epic journey through one of the greatest RPG series ever made, Lunar: Silver Star and Eternal Blue. Each article is a trip back into the neon-lit memories of the past, a celebration of the creativity, risks, and raw energy that defined gaming’s golden years.

Retro Replay Retro Replay gaming reviews, news, emulation, geek stuff and more!

Retro Replay Retro Replay gaming reviews, news, emulation, geek stuff and more!