Introduction: Lunar’s Place in JRPG History

In the early 1990s, role playing games were at a turning point. On one side of the Pacific, Japan had embraced the genre with giants like Final Fantasy IV on the Super Famicom and Dragon Quest V continuing its cultural dominance. In the West, RPGs were still considered a niche market, often dismissed as too slow or too text heavy compared to action driven titles. For players who did give them a chance, however, RPGs were a gateway into deep stories and emotional journeys rarely seen elsewhere in gaming. It was in this climate that Lunar: The Silver Star arrived in 1992, offering something that felt at once familiar and revolutionary.

(HEY YOU!! We hope you enjoy! We try not to run ads. So basically, this is a very expensive hobby running this site. Please consider joining us for updates, forums, and more. Network w/ us to make some cash or friends while retro gaming, and you can win some free retro games for posting. Okay, carry on 👍)

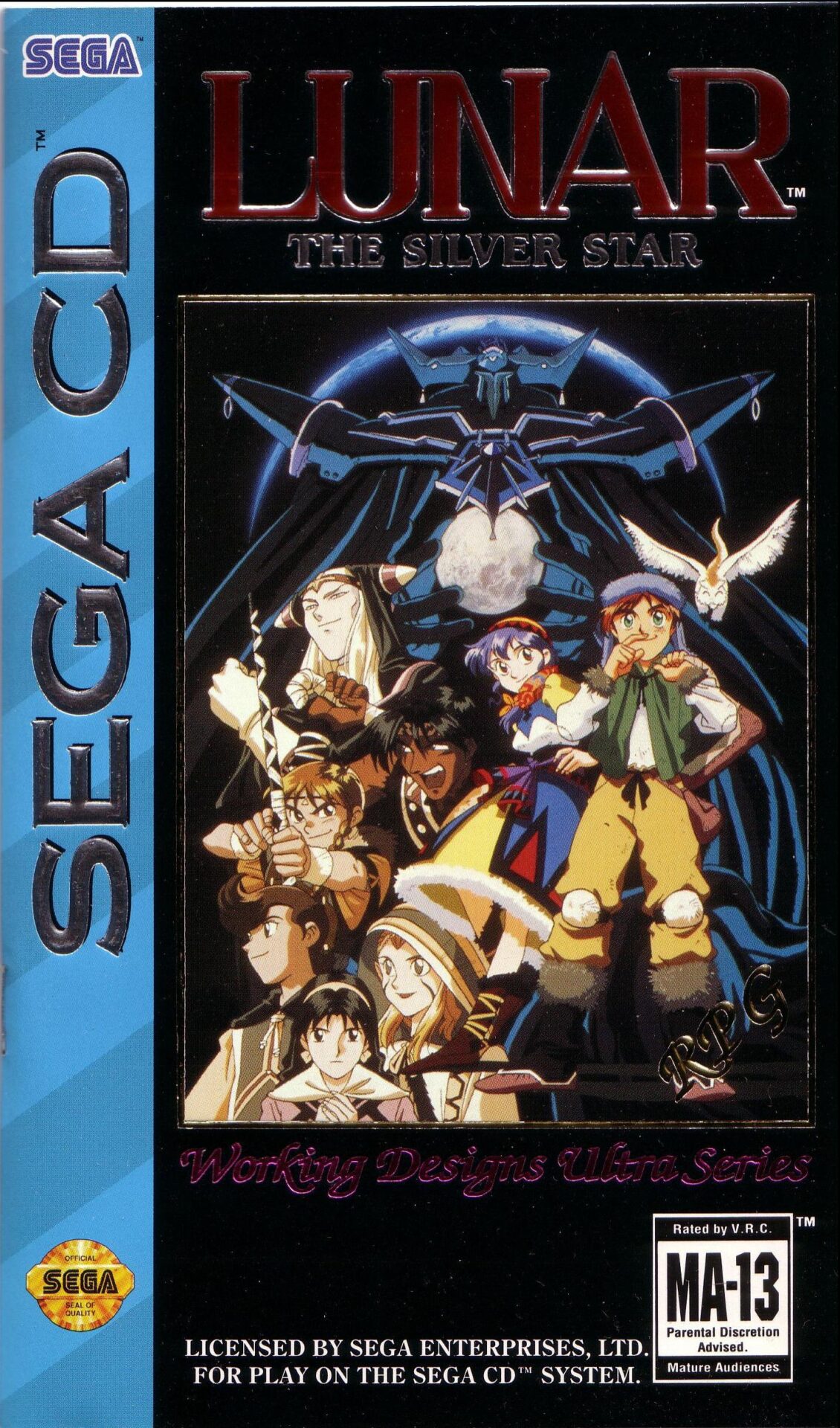

What set Lunar apart was not just its setting or mechanics, but its bold use of technology to tell a story. While most RPGs relied on text boxes and static portraits, Lunar came alive with fully animated anime cutscenes, voice acting, and a sweeping soundtrack that used the Sega CD’s expanded audio capabilities. These elements gave the impression of stepping into an interactive animated film, years before Final Fantasy VII would be credited with popularizing cinematic storytelling in the genre. Critics at the time recognized this leap, with publications like Electronic Gaming Monthly praising the game for pushing the boundaries of what players could expect from console RPGs (SegaRetro entry).

For many players, the memory of playing Lunar is inseparable from the Sega CD itself. The add on was infamous for its small library and high cost, yet owning it meant access to experiences that could not be found anywhere else. Fans recall the excitement of opening the oversized Working Designs jewel cases, flipping through the lush instruction manuals filled with character art, and hearing those first strains of Noriyuki Iwadare’s music swell through tinny television speakers. Working Designs, under the leadership of Victor Ireland, would go on to make the Western releases of Lunar some of the most memorable localizations of the 1990s. Their scripts added humor, cultural references, and a sense of personality that helped the series stand out in a crowded market (Hardcore Gaming 101 history).

Looking back, Lunar’s place in JRPG history is both unique and poignant. It was not the best selling series of its time, nor the most technologically advanced, yet it captured hearts in a way that has kept its legacy alive for decades. It was a bridge between the old era of menu driven RPGs and the new age of cinematic adventures. For those who grew up with it, Lunar was not just another game, it was a storybook world, a dream captured on compact disc, and a reminder that video games could be as moving as any film or novel.

Origins of Game Arts and the Dream of Lunar

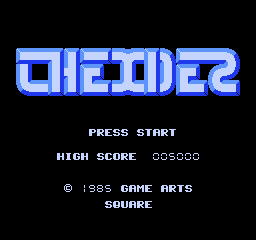

To understand how Lunar: The Silver Star came into being, one must step back to the formative years of Game Arts, a studio that by the late 1980s had already earned a reputation for technological daring. Founded in 1985 by Takeshi Miyaji and his brother Yoichi, Game Arts quickly established itself with Thexder, a side scrolling action game for Japanese home computers that would sell over a million copies worldwide (MobyGames). The company followed with Silpheed in 1986, a groundbreaking shoot em up that blended 3D polygonal graphics with pre rendered video backgrounds, creating the illusion of a fully cinematic space battle. At a time when most games were defined by sprite work and scrolling backgrounds, Silpheed suggested that Game Arts was interested not only in making fun games but in pushing presentation into new territory.

That cinematic ambition would become the cornerstone of Lunar. When the Sega CD was announced, Game Arts saw the add on as a perfect platform to attempt something bold. The CD medium offered vastly more storage than cartridges, meaning higher quality music, voice acting, and animated sequences were now within reach. In interviews, the developers often described Lunar as a “dream project,” born from a desire to make the kind of RPG they themselves had always wanted to play. Writer Kei Shigema, who had experience scripting anime and manga, was brought in to ensure the story carried the emotional weight of a serialized animated drama rather than the typical simple plots of RPGs of the time.

The team also recruited composer Noriyuki Iwadare, who would go on to score both Lunar titles and later become known for his work on Grandia and Phoenix Wright. Iwadare’s music, made possible by the CD format, allowed for orchestral sounding arrangements and vocal tracks that would have been impossible on cartridge hardware. This emphasis on music and narrative created a deliberate contrast with Final Fantasy and Dragon Quest. While those series excelled in scale and polish, Lunar aimed for intimacy, a heartfelt coming of age story with characters who felt more alive through voice and animation. Director Takeshi Miyaji, only in his early twenties at the time, described Lunar as “a chance to make players feel like they were stepping into an anime they could control” (SegaRetro).

The early 1990s were a fertile moment for such experimentation. The CD-ROM was still seen as exotic, a technology that promised to revolutionize how games were made. For Game Arts, the Sega CD was not a gamble but an opportunity to prove that role playing games could evolve into a new form of interactive cinema. By 1992, after months of planning and collaboration between writers, animators, and programmers, Lunar: The Silver Star emerged as the realization of that dream.

Lunar: The Silver Star (1992) – A Cinematic Leap for JRPGs

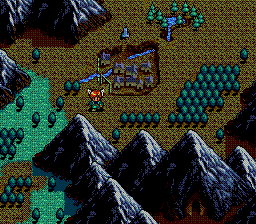

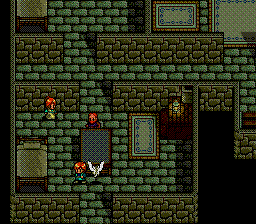

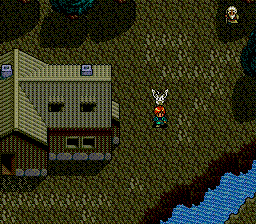

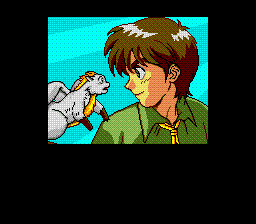

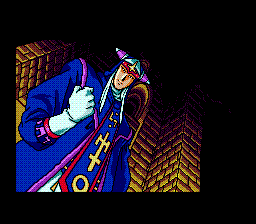

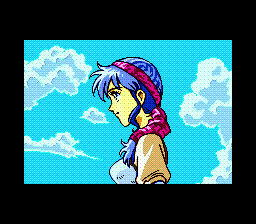

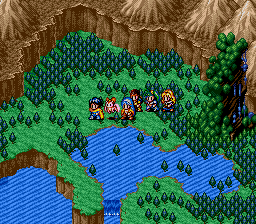

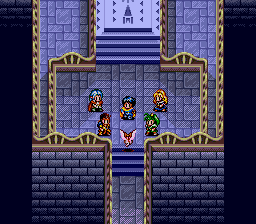

When Lunar: The Silver Star released in Japan on June 26, 1992 for the Sega CD, it was immediately clear that this was not just another role playing game. Its story centered on Alex, a young boy from the quiet village of Burg, who dreams of following in the footsteps of his idol, the legendary Dragonmaster Dyne. Along with his childhood friends Luna, Ramus, and his wisecracking flying companion Nall, Alex embarks on what begins as a simple journey and gradually unfolds into a sweeping tale of love, betrayal, and destiny. Unlike many RPGs of the time that buried emotional beats under layers of combat and grinding, Lunar placed its characters front and center, with arcs that developed naturally over the course of the adventure.

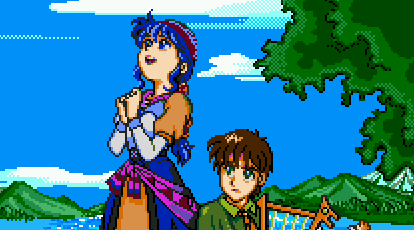

One of the defining features of Lunar was its use of anime cutscenes to punctuate key story moments. These fully animated sequences, produced by Studio Junio, gave players the sense that they were watching a Saturday morning anime come to life. The opening sequence of Luna singing on the hilltop, rendered with expressive hand drawn animation, set the tone for the entire game. Coupled with voice acting, these moments carried an emotional resonance that text alone could not achieve. For many players in 1992, hearing characters speak was a revelation. As critic Kurt Kalata noted, “Lunar felt alive in a way other RPGs of the era simply did not. It was as much a show as it was a game” (Hardcore Gaming 101).

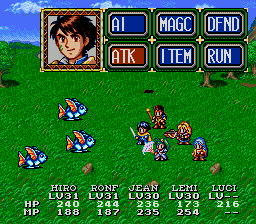

Gameplay wise, Lunar retained the structure of traditional Japanese RPGs. Players explored towns, talked to NPCs, delved into dungeons, and engaged in turn based battles. Yet even here, the game carried subtle innovations. Battlefields were not static screens, but small arenas where character placement mattered. Spells and attacks had ranges, meaning strategy extended beyond simply selecting commands from a menu. This blend of classic mechanics with new wrinkles gave the game a distinctive rhythm. Exploration was enhanced by the lush visuals and music, which took advantage of the Sega CD’s expanded memory to deliver richer graphics and CD quality sound. Composer Noriyuki Iwadare’s score, filled with sweeping themes and memorable character motifs, remains one of the most beloved aspects of the series (RPGFan Soundtrack Archive).

The Sega CD itself played a crucial role in shaping Lunar’s identity. The add on was often criticized for its limited power compared to the Super Nintendo and PC Engine CD, yet in the hands of Game Arts, its capabilities were used to their fullest. The CD audio allowed for professional quality music and voices, while the extra storage enabled the inclusion of dozens of minutes of animated cutscenes. However, the hardware also imposed restrictions. Load times could be long, and the color palette was still limited compared to rival systems. Nevertheless, these technical shortcomings did little to dampen the impression Lunar left on players.

Reception in Japan was strong, with Famitsu awarding the game a respectable 31 out of 40, praising its presentation and storytelling (Famitsu Scores Database). Fans embraced it as one of the Sega CD’s defining titles, a game that justified the expensive add on for those who wanted experiences that could not be found elsewhere. In the words of one contemporary reviewer named Horseflesh from GameFAQs,

When I first bought my Sega CD back in 1993, I was somewhat disappointed with the gameplay of most of the software for the system. Then came Lunar: The Silver Star, the greatest game I have ever played, and probably will ever play.

For many who played it in 1992, Lunar was more than just a game. It was a glimpse of what role playing games could become, a bridge between static menus and cinematic immersion. It was a story of friendship, love, and heroism told with a sincerity that resonated deeply. Even today, players who experienced Alex and Luna’s journey on the Sega CD recall it not just as a milestone in gaming history, but as a personal memory, a time when games first began to feel like stories you could live in.

The History of Working Designs

In the massive mix of North American publishers, Working Designs occupies a curious and beloved niche. Founded in 1986 in Redding, California, the company was small, scrappy, and entirely unlike the giants that dominated the market. By the early 1990s, when most publishers were chasing mainstream hits, Working Designs made its mark by specializing in Japanese RPGs and action titles that might otherwise have never left Japan. For players who discovered them, the Working Designs logo on a jewel case meant something rare—it meant care, humor, and a game you would remember.

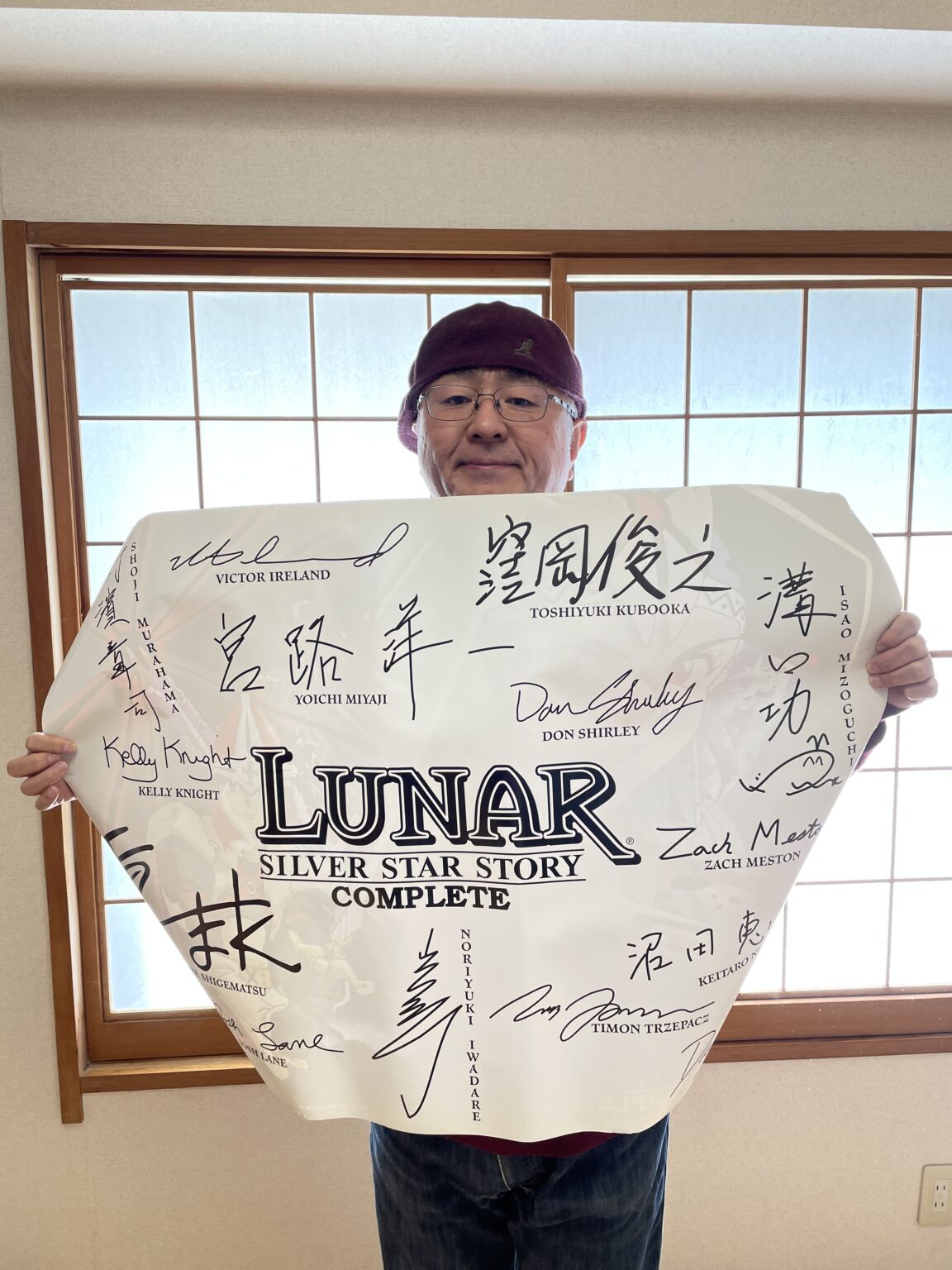

At the center of the operation was Victor Ireland, who served as president, producer, and often the public face of the company. But he was hardly alone. The team included localizers and writers like John Greiner, Ken Behrens, and Monica Vallejo, as well as editors such as John R. Deering, who often lent wit and polish to the English scripts. Voice direction frequently passed through the hands of Ireland himself, though actors like Jenny Stigile (the voice of Luna) and Jackie Powers became fan favorites. On the design side, staff members like Toshiyuki Kubooka were credited for the original Japanese character art, while Working Designs often touched up and adapted visual materials for manuals and packaging. Their QA and design feedback teams, though small, became known for spotting inconsistencies and even suggesting gameplay tweaks that sometimes found their way back to the Japanese developers (MobyGames Working Designs credits).

Working Designs’ early catalog showed their willingness to go against the grain. They brought Cosmic Fantasy 2 and Exile: Wicked Phenomenon to the TurboGrafx-CD, and later turned heads on the Sega CD with releases like Vay and Popful Mail. Each of these titles was accompanied by the lavish packaging that would become their signature. Glossy full-color manuals, oversized jewel cases, and later even bonus items like cloth maps or soundtrack CDs made the games feel like treasures. Long before “collector’s editions” became common, Working Designs treated every release as a premium event.

Their localization style was equally distinctive. Ireland and his team weren’t content with literal word-for-word translation. Instead, they sought to capture the spirit of the original while making it resonate with Western audiences. This often meant adding contemporary jokes, cultural references, and snappy dialogue. Some purists frowned at the liberties, but many fans embraced them, because the scripts carried a voice—one that felt more conversational, more human, than the stilted English that plagued many other RPG translations of the era. This reputation for humor and personality, combined with the boutique packaging, gave Working Designs an identity that felt larger than life.

When Lunar: The Silver Star came along, it was a match made in heaven. Game Arts had built an ambitious CD-ROM RPG bursting with anime sequences and heart, and Working Designs had the editorial boldness and presentation savvy to make it shine in the West. Victor Ireland, along with his small but passionate staff, poured themselves into the project. What emerged was not just another localization but the definitive North American RPG experience of the Sega CD era. For those who owned it, Lunar was proof that a small publisher with big dreams could change how players thought about role playing games forever.

Working Designs and the Western Localization

For most American players, Lunar wasn’t just a Japanese RPG that happened to make its way across the ocean. It was Working Designs’ Lunar, a game that arrived wrapped in thick manuals, glossy character art, and a translation that was anything but ordinary. If you grew up in the mid-1990s and cracked open that oversized Sega CD jewel case, you knew right away that this was something different. Victor Ireland and his small team didn’t just translate games. They treated them like events, the kind of releases you would hold onto, reread the manual before bed, and proudly stack on the shelf.

Ireland himself was famously camera-shy. In a 1998 E3 interview, when asked why his face never showed up in press kits, he laughed it off and said, “I don’t like pictures of the actors, I don’t like pictures of me, because it takes the focus away from the game. It’s not an ego thing.” (LunarNet Interview). That summed up the Working Designs ethos perfectly: keep the spotlight on the world of Lunar, not the people behind it. Yet the irony is that his personality came through loud and clear in the games themselves. Jokes, references, little winks to the player—you could hear Victor Ireland’s voice in the dialogue.

But Working Designs didn’t just punch up lines with humor. They worked hand-in-hand with Game Arts to make sure the English version felt emotionally satisfying. Ireland recalled how the team even convinced Game Arts to tweak the finale of The Silver Star. In the Japanese version, when you climb the icy path to confront Luna, you could simply walk to the top. Working Designs thought that was anticlimactic. “We added the thing where if you got to the top without playing the harp, the last bolt would kill you,” Ireland explained. “So you had to remember to play the harp to remind her, to get to the top of the ice path. They thought that was just the coolest idea, and they did it, and it was great.” That one adjustment turned a throwaway item into an unforgettable emotional key, a symbol of Alex and Luna’s bond that still makes longtime fans misty when they retell the story.

There was a sense of playfulness in the production, too. Ireland admitted to sneaking his own voice into the soundtrack: “The Lunar song, with the ‘Hey Hey’ in the middle… that’s five of me. We shifted them into different pitches so it sounded like a group of people, but I’m all five people. I’m the ‘Hey Hey’.” For fans who sang along to that intro while the anime played on their TV screens, that little anecdote is the kind of thing that turns nostalgia into a smile.

Looking back now, it’s easy to see why Lunar built such a loyal following in the West. Yes, the Sega CD was a struggling add-on. Yes, the audience was small. But those who played it felt like they were part of something special. The mix of heartfelt anime drama, Noriyuki Iwadare’s sweeping score, and a localization that spoke directly to 1990s kids—sometimes silly, sometimes soulful—made Lunar unforgettable. Even when later remakes polished the edges, fans kept returning to those original Working Designs discs, because they carried not just a game, but a whole era’s worth of personality.

Lunar: Eternal Blue (1994) – A True Sequel

When Lunar: Eternal Blue arrived in Japan in December 1994, it felt like something rare: a sequel that didn’t just repeat the formula, but expanded the universe in every direction. For those who first played it on the Sega CD, it was immediately clear that this was bigger, longer, and more emotionally charged than The Silver Star. To many fans, it remains the crown jewel of the series and one of the finest examples of what a CD-ROM RPG could be.

The story unfolded a thousand years after Alex and Luna’s adventure, placing players in the shoes of Hiro, a young explorer who stumbles across Lucia, a mysterious emissary from the Blue Star. Her mission is to save Lunar from an ancient evil, but she quickly learns that she cannot accomplish it alone. Joined by Hiro’s fiery sidekick Ruby, the group embarks on a quest that balances soaring adventure with themes of trust, sacrifice, and heartbreak. Where The Silver Star had the innocence of a coming-of-age tale, Eternal Blue embraced a more mature tone, with bittersweet moments that lingered long after the credits. Fans today still call it one of the most affecting RPG narratives of the 16-bit era (Hardcore Gaming 101).

From a technical perspective, Eternal Blue stretched the Sega CD to its limits. The game featured over fifty minutes of fully animated cutscenes—nearly double what the first game offered—and an enormous amount of voiced dialogue. Composer Noriyuki Iwadare returned to score the project, and his work has since been celebrated as some of the best of the decade. Tracks like “Lucia’s Theme” and “Hiro’s Adventure” paired beautifully with the game’s emotional weight, showing how CD audio could elevate an RPG soundtrack beyond the limitations of cartridges. As one reviewer at RPGFan later put it, the music was “where the sound score really gets a lift, though. Noriyuki Iwadare put out, in my opinion, his best soundtrack ever. So many of the themes for this game are masterpieces. From the peaceful Taben’s Peak to the ever-pressing Zophar Domain, the quality of composition shows. And having Working Designs put together the famous “Star Dragon Tower” only raised the bar that much more.”

The gameplay refined the foundations of the first Lunar while offering more depth. The semi-tactical battle system returned, with character placement and spell ranges creating layers of strategy beyond simple menu selection. Dungeons were longer, more complex, and often tougher. The game’s length was staggering for the time, with many playthroughs stretching well past forty hours. One infamous feature was the save system, which required players to spend magic experience points to record progress. While this added tension, it frustrated many, and Working Designs adjusted it in the North American release to make it less punishing. Fans often discuss this change as emblematic of the publisher’s sensitivity to Western tastes.

Reception among players was glowing. Even years later, bloggers and fans still speak of its impact. A fan review at RPG-O-Mania highlights its

“I cannot think of RPG fans that do not like Lunar: Eternal Blue Complete. It’s got a warm-hearted, yet mature story, a cool cast of characters, impressive anime-styled cutscenes and a challenging combat system which is pretty fair on top of that”.

The consistency across fan voices speaks volumes: Eternal Blue remains beloved not just as a product of its time, but as a timeless example of storytelling through video games.

What makes Eternal Blue unforgettable is the way it pushed beyond nostalgia even as it was being born. It delivered a sense of scale and emotion few other 16-bit RPGs matched, while still holding onto the intimacy that made Lunar special. For players who experienced Hiro and Lucia’s story, there was a sense that this was not just another RPG—it was an epic you lived, one that made you laugh, weep, and reflect long after the Sega CD powered down.

Remakes, Ports, and the Legacy of Lunar

By the mid-1990s, the Sega CD was already slipping into obscurity. It had been a daring machine, but the mainstream turned away quickly, leaving many of its most ambitious titles stranded on an add-on most players never owned. Lunar could have easily been one of those forgotten experiments, a memory preserved only in the collections of Sega diehards. Instead, the series became one of the most frequently re-told sagas in RPG history, kept alive by a remarkable series of remakes and ports that allowed Alex, Luna, Hiro, and Lucia to live again for new audiences. Each version was a little different, each carried its own personality, but all of them helped carve Lunar’s legend.

The first big revival came on the Sega Saturn in 1996 with Lunar: Silver Star Story. Unlike so many remakes that strip away charm, this was a complete re-imagining. Game Arts rebuilt the game with fresh art, fully animated cutscenes produced by Studio Gonzo, and a heavily expanded script. When it reached the PlayStation in 1998 as Lunar: Silver Star Story Complete, it was a revelation for players who had never touched a Sega CD. In North America, Working Designs made sure it felt like an event. The box included a cloth map, soundtrack CD, and hardcover art book. Unboxing it was like unwrapping treasure, and many fans still remember the ritual of laying out the extras on the floor before booting up the game for the first time. Years later, retrospectives like EGM Now would call Silver Star Story Complete one of the best JRPGs ever made, not just for its mechanics but for the way it made players feel part of something bigger.

That same philosophy carried over into Lunar 2: Eternal Blue Complete, which arrived for the PlayStation in 2000. The remake pushed even further, with longer cutscenes, more voice acting, and expanded character moments. But what most fans remember first is the collector’s edition packaging. Working Designs loaded the box with character standees, a pendant, another cloth map, and even a “Making of” disc. Opening it felt closer to opening a Christmas present than a video game. Retro reviews like Operation Rainfall still gush about the presentation, calling it a release that captured the glory days of physical extras.

As the 2000s rolled on, Lunar found ways to fit into smaller screens. Lunar Legend on the Game Boy Advance (2002) offered a simplified retelling of the first game, stripped down for handheld play. Some longtime fans bristled at the compromises, but for younger players it was often their first chance to journey under the Silver Star. Later, Lunar: Silver Star Harmony on PSP (2010) attempted another reinvention, with redrawn character art and re-recorded voice acting. While a few veterans missed the Working Designs humor, sites like RPGFan praised Harmony for polishing the experience, making it more approachable for a generation used to sleeker RPGs. These portable versions may not have had the grand packaging of their console predecessors, but they kept Lunar alive at a time when many 90s RPGs were fading into obscurity.

The most dramatic revival came in 2025 with the release of the Lunar Remastered Collection on modern platforms. For the first time, both Silver Star Story Complete and Eternal Blue Complete were bundled together with widescreen support, sharper visuals, dual-language voice tracks, and long-requested quality-of-life upgrades like faster battles and cleaner menus. Critics were impressed. Shacknews called it “a respectable remaster that doesn’t get in its own way,” while XboxEra praised the inclusion of both “Classic” and “Remastered” modes, letting fans choose whether they wanted the authenticity of the originals or the polish of a modern update. RPGSite echoed this, noting how the remasters “don’t mess with the secret sauce all that much,” instead letting the heart of the games shine through with subtle but important improvements.

What all these remakes and ports prove is that Lunar’s story was never meant to be trapped on one machine. It evolved, shifted, and retold itself across decades, yet somehow always kept the heart of the original intact. Whether it was the oversized jewel cases of the Sega CD, the treasure-packed PlayStation “Complete” editions, or the sleek modern remaster toggling between Classic and Remastered modes, Lunar has always been presented with love. That enduring care explains why the series feels less like a memory locked in the 1990s and more like a living story, one that still finds new audiences and sparks the same emotions in players decades later. I posted the hype trailer here, a while ago.

Fan Culture and Community Legacy

If you ask longtime fans why Lunar has endured, most won’t point first to sales charts or critic scores. They’ll talk about the community, the way fans themselves refused to let the series fade even when Game Arts and publishers had long since moved on. In the mid-90s, when the internet was still young, Lunar fandom thrived in the cracks — on AOL message boards, Usenet groups, and home-built GeoCities pages filled with GIFs and MIDI versions of “Wings.” There weren’t many of us, but the passion was intense, and that intimacy made being a Lunar fan feel like belonging to a secret club.

The crown jewel of this fan movement was LunarNET, launched in the late 1990s and still alive today. LunarNET became the definitive English-language archive of all things Lunar, from character bios to detailed walkthroughs, magazine scans, and exclusive interviews with Victor Ireland himself. Many fans first learned about Working Designs’ quirky localization choices or the Japanese differences through its forums and articles. The site even helped connect people directly to Working Designs during the PlayStation remakes, making the line between fan and developer thinner than it had been for most series. To this day, LunarNET remains an indispensable resource for anyone exploring the history of the games.

Beyond websites, Lunar fandom also spilled into the world of fan creativity. VHS fansubs of the Lunar: The Silver Star and Lunar: Eternal Blue OVAs circulated at anime conventions in the late 90s, long before streaming made such things accessible. Zines and fanfiction filled with stories of Alex and Luna’s future, or “what if” tales of Hiro and Lucia, were shared in the same way — traded in mailing lists or distributed on Angelfire sites. Cosplayers brought Luna’s iconic songstress outfit or Lucia’s ethereal design to life at early anime cons. Decades later, YouTube and Twitch would keep that creativity alive: fans uploading covers of Lunar’s music, re-animating cutscenes, or live-streaming Sega CD longplays with commentary about how the games shaped their childhoods.

Preservation has been another key part of the community. With Sega CD hardware growing rarer, emulation projects became a lifeline. Fans traded ISO images, documented bugs, and wrote detailed guides on how to get the original discs running in emulators like Kega Fusion and RetroArch. For many younger fans, these efforts were the only way to experience the Sega CD versions, which had become prohibitively expensive on the secondary market. Rather than hoard the games, the community often emphasized sharing — making sure the world of Lunar stayed playable and accessible, even if Sega and Game Arts weren’t keeping it in circulation.

What makes Lunar’s fan culture feel unique compared to the giants of the JRPG world is its intimacy. Final Fantasy or Dragon Quest have sprawling global fanbases, but Lunar’s community feels like a tight-knit village. Fans recognize one another on forums, share stories about their first time hearing Luna’s song, or debate endlessly whether the Sega CD or PlayStation versions are “truer.” This closeness mirrors the games themselves: stories not of armies or empires, but of small groups of friends whose bonds matter more than the fate of the world. Lunar’s fans, perhaps unconsciously, reflect that same ethos.

The Silver Star’s Lasting Light

There are games that slip away quietly, fading into bargain bins and forgotten rental shelves. And then there are games like Lunar, which linger like a song you cannot get out of your head, even years after you last heard it. For those who played these titles on the Sega CD in the early 1990s, the memories are often tied as much to the moment of discovery as to the content itself: the first time hearing Luna’s voice through a tinny television speaker, the awe of seeing an anime cutscene run from a compact disc, the realization that video games could make you feel something deeper than reflexive joy or frustration.

Part of what makes Lunar’s light endure is the balance it struck. On the one hand, these were products of their time: technical showcases designed to prove that Sega’s CD add-on could deliver experiences unlike anything on cartridge. On the other hand, they reached beyond the marketing pitch. They told stories that felt timeless — stories of ordinary people thrust into extraordinary roles, of love found and tested, of sacrifice made and remembered. Alex’s determination to reach Luna, Hiro’s growing bond with Lucia, even the side characters who made you laugh or occasionally annoyed you — they all worked together to create an impression of a world you wanted to live in.

The way Lunar blended its elements was particularly striking. Anime cutscenes weren’t entirely new in the early 90s, but rarely had they been integrated so seamlessly into gameplay. Noriyuki Iwadare’s scores weren’t just background music; they were emotional signposts, amplifying joy, fear, and heartbreak. The voice acting, imperfect as it sometimes was, gave a human texture to a medium that had long relied on silent text boxes. Looking back, it feels almost miraculous that all these pieces came together with such resonance on hardware that was, by any technical measure, fragile and limited.

And then there is the community. Unlike the towering monoliths of Final Fantasy or Pokémon, Lunar was always the story of a smaller village. Its fans weren’t legion, but they were devoted, and that devotion gave the series a second, third, even fourth life through remakes and fan preservation. From LunarNET archiving developer interviews, to cosplayers bringing Lucia and Luna to life on convention floors, to YouTubers streaming the Sega CD versions with affection, the series has lived on in the care of those who loved it most. The Lunar Remastered Collection of 2025 didn’t emerge in a vacuum — it was born from that sustained passion, from decades of people telling anyone who would listen, “You have to play Lunar at least once.”

In a way, this is Lunar’s true legacy. Not the sales charts, not the reviews, not even the debate over which version is the “definitive” one. The legacy is in the memories. It is in the cloth maps still folded in boxes, the soundtracks tucked into CD wallets, the countless forum posts comparing favorite lines from the Working Designs scripts. It is in the way players remember late nights lit only by CRT glow, with Luna’s voice echoing through the living room. Lunar is not just a series of games — it is a shared experience, a thread running through decades of gaming history, tying together the people who played, who remembered, and who kept telling the story long after the credits rolled.

The Silver Star’s light may have dimmed in the market, but it still shines in memory. And sometimes, as the remakes remind us, memory is enough to keep a star alive.

As we close the book on Lunar, this marks the second entry in our ongoing History of series, where we dive deep into the stories behind the games that defined eras and shaped memories. Our first journey took us through the bloody arcades and haunted hallways of Namco’s cult classic Splatterhouse, tracing its full timeline from obscurity to legend. If you missed it, be sure to read the complete feature here: History of Splatterhouse: Complete Timeline. Each of these articles is meant to be both a nostalgic look back and a historical record, and together they form a growing library celebrating the medium we love.

FAQ – History of Lunar: The Silver Star & Eternal Blue

| Question | Answer |

|---|---|

| What is Lunar: The Silver Star? | Lunar: The Silver Star is a Japanese role-playing game (JRPG) originally released for the Sega CD in 1992 by Game Arts. It follows Alex, a young adventurer, on a journey with his childhood friend Luna to become a Dragonmaster and save the world. |

| When was Lunar: Eternal Blue released? | Lunar: Eternal Blue, the sequel, was released in Japan in December 1994 for the Sega CD. It reached North America in 1995 through Working Designs. The story is set 1,000 years after The Silver Star and features new heroes Hiro, Lucia, and Ruby. |

| Who localized the Lunar games in North America? | Working Designs, led by Victor Ireland, localized both Lunar: The Silver Star and Lunar: Eternal Blue for the Sega CD, and later their PlayStation remakes. Their localizations are remembered for humor, collector’s editions, and extras fans still love. |

| What makes Lunar’s soundtrack memorable? | Composer Noriyuki Iwadare created rich, emotional scores for both games. Songs like “Wings” from The Silver Star and “Lucia’s Theme” from Eternal Blue remain iconic, blending classic JRPG sounds with anime-inspired vocals. |

| What are the “Complete” versions of Lunar? | The “Complete” editions were full remakes for the Sega Saturn and PlayStation. Lunar: Silver Star Story Complete and Lunar 2: Eternal Blue Complete featured new art, expanded cutscenes, full voice acting, and legendary collector’s boxes from Working Designs. |

| What is LunarNET? | LunarNET is the definitive fan site for the series, launched in the late 1990s. It archives interviews, guides, artwork, and forums, and remains the hub of Lunar fandom today. |

| Did Lunar ever come to handheld systems? | Yes. Lunar Legend (Game Boy Advance, 2002) was a streamlined retelling of The Silver Star. Later, Lunar: Silver Star Harmony (PSP, 2010) updated graphics and voice acting for a modern audience. |

| What is the Lunar Remastered Collection? | Released in 2025, the Lunar Remastered Collection brought both Silver Star Story Complete and Eternal Blue Complete to modern platforms with widescreen support, faster battles, dual-language audio, and HD cutscenes. Reviews at Shacknews and XboxEra praised it as a faithful update. |

| Why do fans debate which version is “definitive”? | Some fans prefer the raw emotion of the Sega CD originals, others love the polish of the PlayStation “Complete” editions, and still others champion the portability of GBA/PSP versions. The Remastered Collection offers both “Classic” and “Remastered” modes, keeping the debate alive. |

| What is Lunar’s legacy in RPG history? | Lunar is remembered for combining heartfelt storytelling, anime cutscenes, memorable music, and rich characters into one experience. Though not as commercially massive as Final Fantasy, it remains one of the most beloved cult JRPGs of all time. |

Retro Replay Retro Replay gaming reviews, news, emulation, geek stuff and more!

Retro Replay Retro Replay gaming reviews, news, emulation, geek stuff and more!