1987–1989: Birth of a Horror Icon

If you grew up in the late 80s, you know that arcades were already loud, neon-drenched temples of temptation. Yet every once in a while, a cabinet would appear that felt different– darker, more dangerous, the sort of thing you’d whisper about with your friends at school. For many of us, that game was Splatterhouse.

(HEY YOU!! We hope you enjoy! We try not to run ads. So basically, this is a very expensive hobby running this site. Please consider joining us for updates, forums, and more. Network w/ us to make some cash or friends while retro gaming, and you can win some free retro games for posting. Okay, carry on 👍)

Developed by Namco on its System One board, Splatterhouse didn’t just want to entertain; it wanted to shock. Chief planner Kazumi Mizuno put it plainly in a 1988 roundtable interview later translated by Shmuplations: “Our design goal for Splatterhouse, simply put, was to make a serious horror game.” That was a radical statement in an era dominated by cute mascots, colorful shooters, and puzzle games.

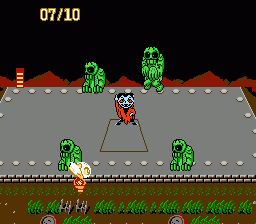

The dev team pushed boundaries right away. Early builds featured realistic zombies and red blood, but Namco management balked. As Mizuno recalls: “If your game is going to be about killing, killing, killing, you cannot make it realistic.” The compromise? Switch the blood to a fluorescent green and make enemies more monstrous, less human. Far from weakening the game, the changes made it pop on arcade screens, where garish colors drew attention like moths to flame.

Composer Yoshinori Kawamoto added another layer of handmade horror. He described standing in a booth with other staff, recording their own groans and screams for the game’s eerie sound effects. In fact, he even performed Jennifer’s possessed voice himself. Mizuno, for his part, demonstrated the sound of a decapitation by making a plosive “pop” with his lips, a sound that became one of the game’s signature audio cues. It’s the kind of detail only possible in an era where small, tightly knit teams poured themselves into a project, improvising and experimenting at every turn.

When the cabinet finally launched in Japan in 11/1988, and in the West in early 1989, it was unlike anything else on the floor. You didn’t play as a knight, a space marine, or a cutesy adventurer. You played as Rick Taylor, a college student resurrected by a cursed mask after being dragged into West Mansion with his girlfriend Jennifer. What followed was a nightmare march through a living, breathing house of horrors, armed with fists, a slide kick, and, most famously, a two-by-four that delivered a meaty thud with every swing.

The imagery was impossible to ignore. Splattered organs, grotesque wall-crawlers, and a chapel boss that prominently featured an inverted cross made it clear Namco was pushing buttons deliberately. Kids huddled around the cabinet and whispered about how it reminded them of Friday the 13th or Evil Dead. Mizuno later remembered with pride that during location tests, “the kids were excitedly naming the movies they recognized.” That sense of illicit recognition made the game feel dangerous, like a secret club for those who loved late-night VHS horror rentals.

In the West, the game courted controversy immediately. According to Arcade History, some arcades outright refused to carry the machine due to its gore and religious imagery.

Licensed to Atari Games for distribution in the USA (February 1989). Only 100 PCBs were produced by Atari because the game was banned in most arcades in the USA due to its violent nature as well as some questionable bosses such as the chapel boss (The inverted cross). Splatterhouse was the first game to get a parental advisory disclaimer.

-Arcade History

Distribution was handled by Atari Games in North America, but numbers were limited, making sightings of a cabinet all the more thrilling. The inverted cross in Stage 4 drew complaints, and parents were quick to condemn the game as a corrupting influence. All of which, of course, only fueled its mystique among young players.

For many of us who were kids at the time, walking up to a Splatterhouse cabinet felt like sneaking into a restricted section of the video store. You knew you weren’t supposed to be there, and that made it irresistible. The sound of Rick’s board smacking an enemy skull wasn’t just an effect; it was a punchline in a joke you weren’t supposed to tell.

And then, in 1989, Namco doubled down with one of the strangest pivots in gaming history. The Famicom-exclusive Splatterhouse: Wanpaku Graffiti arrived in Japan as a chibi-styled parody. Suddenly, Rick was pint-sized and wide-eyed, battling cute-but-creepy monsters in a tongue-in-cheek riff on horror tropes. There’s even a scene where a vampire does a pitch-perfect spoof of Michael Jackson’s “Thriller” dance. Despite the lighter tone, it retained the same DNA: masks, mansions, and monsters.

As the fan archive West Mansion reminds us, Wanpaku Graffiti was actually the first Splatterhouse title to hit home consoles, predating the TurboGrafx-16 port of the arcade game. For Japanese players, it was their introduction to the series. And while some hardcore fans dismissed it as too silly, others saw it as proof that Splatterhouse had already transcended a single mood. It could be grim, it could be funny… but it always carried that same pulse.

By the end of the 1980s, Splatterhouse had already built a reputation. It was the “forbidden fruit” of arcades, a cult favorite among horror fans, and a name whispered by kids who dared each other to play it. And for Namco, it was just the beginning of a bloody march through the 1990s.

1990 to 1993 Splatterhouse Comes Home

If the late 80s arcade scene gave Splatterhouse its reputation as forbidden fruit, the early 90s brought the question every kid asked back then: could you actually play it at home. The answer was yes, but with a twist.

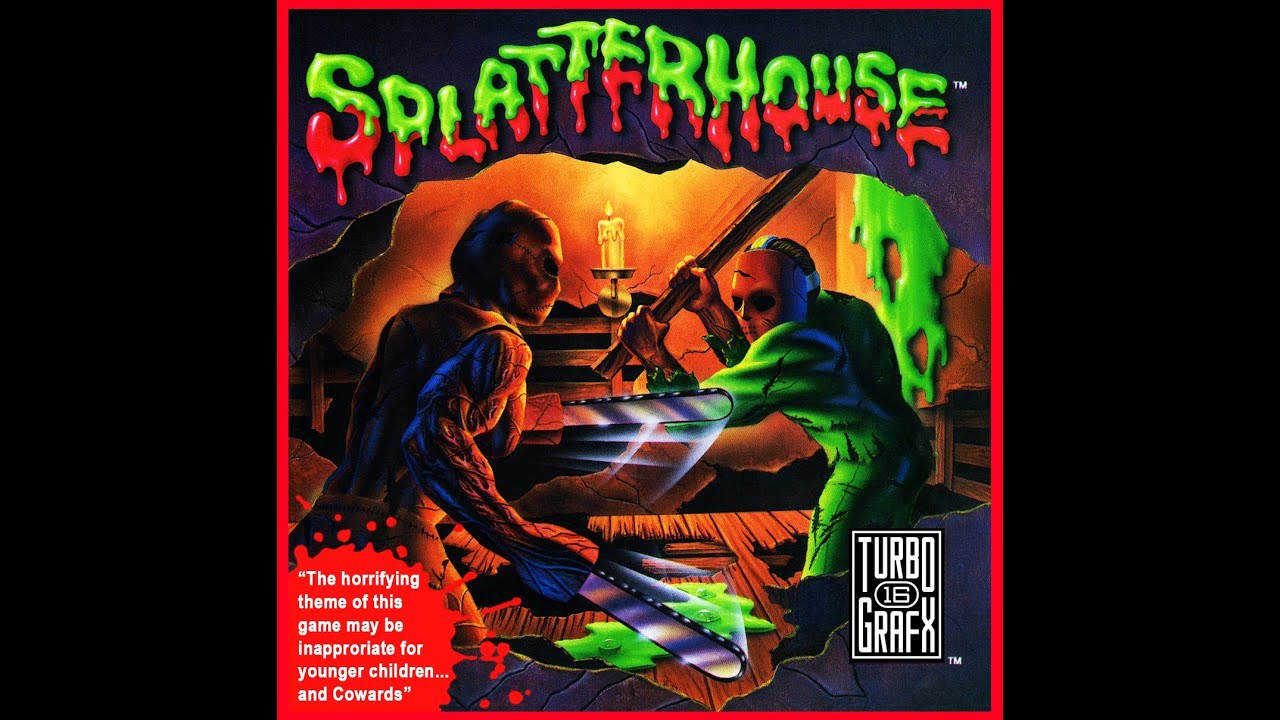

In 1990 Namco ported the arcade game to the PC Engine in Japan and the TurboGrafx 16 in North America. For many of us in the West, this was our first chance to bring the mask and the mansion into the living room. The box itself leaned into the controversy. It carried a bold mock advisory label warning that the game was not for young children or cowards. That kind of cheeky marketing only made kids want it more, the same way a Parental Advisory sticker made a CD feel cooler.

Of course, the port was not identical to the arcade. Hardware limitations trimmed sprite detail and simplified some animations. More importantly, regional sensitivities drove notable edits. Rick’s iconic white mask became red with black accents in the TurboGrafx 16 version, an obvious move to distance him from Jason Voorhees of Friday the 13th. Backgrounds in the infamous chapel stage were altered, with the inverted cross boss transformed into a floating severed head and cathedral arches removed altogether. Even small details, like obscene gestures from crawling hands, were scrubbed out. Wikipedia’s Splatterhouse page lists these edits in detail, and they have been dissected for decades by preservationists and fans.

For players who discovered Splatterhouse through this port, the changes hardly mattered. The mood was intact. The sound of Rick’s two by four connecting still thudded through living rooms. But if you had spent time on the arcade cabinet, you could feel the edges sanded off. It was like renting a VHS copy of a horror movie that had been edited for television. You got the story, but you missed a few of the dangerous laughs.

In Japan, another version was brewing that remains a grail for collectors. In 1992 Namco and Ving released Splatterhouse for the FM Towns Marty, a home computer console hybrid. This edition was nearly arcade perfect. Sprites were crisp, sound was faithful, and for the first time fans could experience the arcade game without compromise in their living room. Today, that disc commands steep prices on the secondhand market and is celebrated as the purest home version of the original Splatterhouse until Hamster’s Arcade Archives arrived decades later.

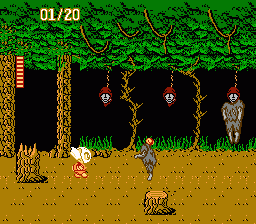

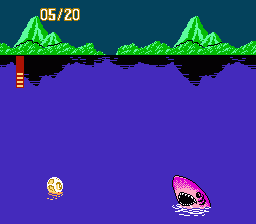

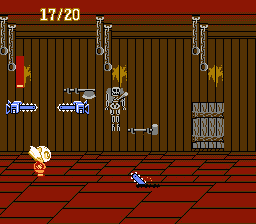

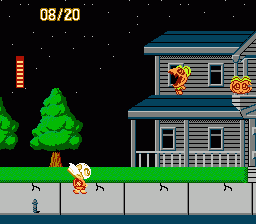

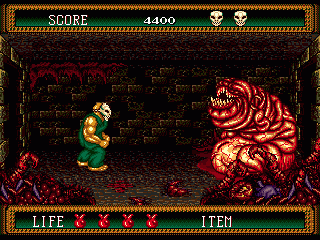

By this point the Splatterhouse name carried weight. It was no longer just a controversial cabinet. It was a brand. In 1992 Namco and Now Production pushed the story forward with Splatterhouse 2 on the Sega Genesis. The game continued Rick’s saga, picking up after the events of the original with Jennifer’s soul still in peril. The gameplay refined the arcade formula with tighter controls, nastier enemies, and an atmosphere that leaned hard into grotesque visuals. The mask whispered again, and Rick answered by walking deeper into the nightmare.

Then came 1993 and Splatterhouse 3, a dramatic shift that turned the series from linear arcade action into something closer to a survival horror experiment. Rick is older now, married to Jennifer, with a son named David. The mansion is back, bigger than ever, and the evil inside has grown. For the first time the game featured branching paths and multiple endings, depending on how quickly you saved family members and defeated bosses. A visible timer ticked down as you moved through each floor of the mansion, raising the stakes. Would you save Jennifer. Would you reach David in time. The answers changed with every playthrough.

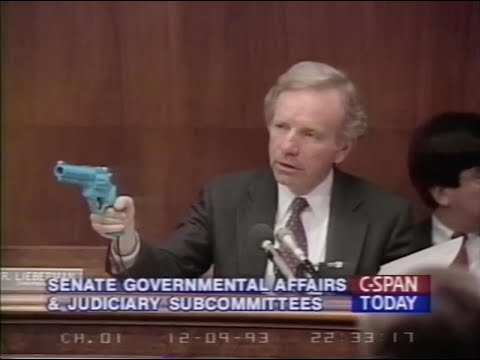

Splatterhouse 3 also holds a special place in gaming history for being one of the earliest console games to ship with an official age rating, courtesy of Sega’s Videogame Rating Council. This was before the ESRB existed, when games like Mortal Kombat and Night Trap were fueling congressional hearings. Splatterhouse had been pushing those boundaries for years, and here it was helping shape the future of ratings systems.

For players in the early 90s these were formative experiences. Many of us remember renting Splatterhouse 2 or 3 on a Friday night, sneaking it past cautious parents, and playing with the lights off to make the mansion feel real. The Genesis sequels proved that Splatterhouse could evolve beyond arcade shock value into a series with real narrative ambition. It was still about smashing monsters with boards and cleavers, but now it was also about family, sacrifice, and the curse of the mask.

By the end of 1993, Splatterhouse had carved out its place in the pantheon of cult classics. It had lived as a scandalous arcade cabinet, a censored console curiosity, a collector’s grail, and a pair of Genesis sequels that dared to tell a deeper story. For fans of horror and retro gaming, the early 90s were the golden years when Splatterhouse was alive and dangerous in the living room.

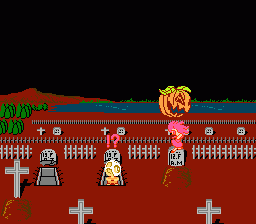

- Splatterhouse 2 for the Sega Genesis

- Splatterhouse 2 for the Sega Genesis

- Splatterhouse 2 for the Sega Genesis

1994 to 2006 The Quiet Years and the Rise of Fandom

By the mid 90s Splatterhouse had already left a trail of controversy and cult devotion. The Genesis duology gave players something to hold onto, but after 1993’s Splatterhouse 3, Rick and the mask vanished from the release schedules. The arcade was changing. Home consoles were shifting to 3D, and Namco itself was moving its resources to heavy hitters like Tekken, Ridge Racer, and Soulcalibur. In that new world, Splatterhouse looked like a relic of the VHS horror era.

Yet for fans who had played the games in the late 80s and early 90s, the silence did not feel like the end. Instead, Splatterhouse began to live as memory, whispered about in magazines, traded in playground stories, and replayed on aging hardware. To truly understand these years, you have to blend nostalgia with an academic eye. On the one hand, they were years of longing for sequels that never came. On the other, they reveal how fan culture began to fill in the gaps and preserve what the companies left behind.

Magazines, memory, and the “forbidden game” aura

In the 90s, long before YouTube or digital archives, gaming magazines were the lifeblood of retro culture. Splatterhouse would surface in “Top Ten Most Controversial Games” lists, or in retrospectives that reminded readers of its gore and notoriety. Writers leaned on the game’s reputation, highlighting the inverted cross boss or the parental warnings on the TurboGrafx 16 box. In many ways, Splatterhouse’s absence only magnified its reputation. Without new titles to dilute the brand, the name remained frozen in amber as the game “too scary” for its time.

Players who rented the Genesis carts or found the TurboGrafx 16 version in bargain bins often remembered them as illicit treasures. Anecdotes circulated of parents returning cartridges after seeing the blood, or of arcades that covered up cabinet art with tape to make it less offensive. Whether every story was true hardly mattered — the legend was alive. Splatterhouse was remembered not only as a game but as an experience you were not supposed to have.

Fan preservation and the birth of West Mansion

The real lifeline during these years was the rise of online fan communities. By the late 90s and early 2000s, the internet had become a haven for retro enthusiasts to document the games they loved. Out of that era came West Mansion The Splatterhouse Homepage, the definitive fan archive for the series.

West Mansion is more than a website. It is a monument to how fan dedication can preserve a franchise during its dormant years. The site cataloged every release, documented the censorship differences between regions, hosted magazine scans, and even secured interviews with developers of both the classic games and the later 2010 reboot. It is not an exaggeration to say that much of the detailed knowledge about Splatterhouse’s history would have been lost if not for this effort.

For scholars of retro gaming, West Mansion is a perfect example of fan-driven historiography. In the absence of official collections or academic studies, fans themselves acted as archivists. They traced release dates, preserved promotional art, and even hosted long-form essays on the cultural meaning of Splatterhouse. This fan scholarship ensured that the series remained more than just a line in a Namco catalog — it became a living archive.

Nostalgia in the living room

Many of us dusted off our old cartridges or hunted down copies in pawn shops and flea markets. Playing Splatterhouse in the late 90s felt like rewinding a VHS tape to relive a forbidden thrill. The sprites might have looked dated next to the PlayStation’s polygons, but the mood was still there. The mask still whispered. The mansion still breathed. And for those of us who grew up with it, the act of replaying was less about challenge and more about memory, remembering a time when just seeing blood in a video game felt like getting away with something.

By the early 2000s, emulation communities gave Splatterhouse another life. MAME preserved the arcade original, while fan translations and ROM hacks of Wanpaku Graffiti spread across forums. Academic observers of digital preservation often point to this period as the birth of serious emulation culture, and Splatterhouse was right there, being kept alive by hobbyists with a passion for both horror and history.

Looking back, 1994 to 2006 was not just a gap in releases , it was a gestation period. The brand lived in nostalgia, in magazines, in fan archives, and in the growing emulation scene. The silence gave Splatterhouse a kind of mythic aura, so when rumors of a revival began in the mid 2000s, fans were ready. The mask had been waiting in the shadows, and everyone who had ever played the games as kids was eager to see it grin again.

2007 to 2010 Revival and Rebirth

By the mid 2000s, it felt like Splatterhouse had become one of those names you whispered about in retro gaming circles but never expected to see again. The 16-bit cartridges were collector’s items, the arcade cabinet was a rare find, and most younger players only knew of the series from “most controversial games” lists in magazines or early websites. Yet in 2007, something stirred.

2007 Wii Virtual Console and the return of the TurboGrafx

In 2007 Nintendo’s Wii Virtual Console quietly resurrected the TurboGrafx 16 version of Splatterhouse in Japan, North America, and Europe. For some, it was a disappointment — this was the censored console port, with its red mask and toned-down visuals, not the raw arcade original. But for many retro gamers, the reissue was still monumental. It meant Splatterhouse was no longer a memory preserved only on aging hardware and in emulators. It was a living product on a current storefront, available for download with a few clicks.

I remember the feeling of booting up that Virtual Console version. Even with its edits, even with its compromises, the thud of Rick’s two by four still carried weight. There was something surreal about playing what had once been the “forbidden” game, now nestled right alongside Mario and Zelda on a Nintendo service. It was as if the rebel had been invited back into the house, though it still carried the scars of censorship.

From an academic perspective, this release signaled how companies were beginning to embrace retro reissues not just as nostalgia fodder but as part of the larger trend of game preservation. The Virtual Console became a gateway for younger players who had never owned a TurboGrafx 16, and Splatterhouse was suddenly in their living rooms, framed less as scandal and more as history.

2008 Rumblings of a reboot

Then, in 2008, Namco Bandai announced something fans had hardly dared to hope for: a brand-new Splatterhouse for PlayStation 3 and Xbox 360. The whispers of West Mansion’s forums turned into a roar. Could the mask really return in the modern age of high-definition graphics and cinematic gameplay.

At the time, Namco Bandai producers Dan Tovar and Mark W Brown gave a lengthy interview to Sega-16 that reads today like a mission statement. They promised that Splatterhouse would stay true to its roots while taking full advantage of modern hardware. “We are aiming for people to almost smell how disgusting things look on screen,” one producer said. Another added, “You will absolutely be able to tear the environments apart.”

The team also leaned into the mythos of the mask, clarifying that when it was first designed, hockey had not even been invented, distancing it once again from the Jason Voorhees comparison. They envisioned Rick not just as a survivor, but as a brutal, primal warrior with a body that could be ripped apart and regenerated in front of the player. Arms torn off in combat would eventually grow back, reinforcing the grotesque, grindhouse vibe.

For fans reading that Sega-16 interview in 2008, the excitement was palpable. Here was a team promising that Splatterhouse would not just return, but explode into the modern era with blood, gore, and heavy metal thunder.

2009 BottleRocket controversy

But in 2009, the dream nearly fell apart. Namco Bandai had originally contracted the game to BottleRocket Entertainment, a studio formed by veterans who had worked on The Mark of Kri. Then, in February 2009, Wired broke the story that Namco Bandai had abruptly pulled the project, repossessing development kits and assets in what the press described as a humiliating takeover (Wired report).

The reasons for the handoff were murky. Some sources suggested performance issues, others pointed to missed deadlines. A month later, Wired published a follow-up in which BottleRocket defended itself, claiming it had not missed milestones during the 18 months it worked on the project and that Namco’s decision had little to do with performance (Wired follow-up).

For fans, it was a nerve-racking time. Rumors swirled that the game might never see release. The forums buzzed with speculation. Would Splatterhouse’s long-awaited revival die before it even shipped. Or would Namco’s internal teams salvage the project in time.

2010 The reboot arrives

Against the odds, Splatterhouse did ship in November 2010 on both PlayStation 3 and Xbox 360. And when it landed, it was loud, brash, and gloriously gory. Rick was back, bigger and meaner than ever. Jennifer was once again in peril. Dr. West lurked in the shadows. The mansion was alive with enemies begging to be reduced to pulp.

What set the 2010 reboot apart, though, was its sheer commitment to fan service. Alongside the new 3D action brawler, Namco Bandai included the original trilogy, the arcade Splatterhouse, Splatterhouse 2, and Splatterhouse 3… as unlockables. That meant every disc was not just a modern reboot, but a mini-museum of the series. For retro gamers, it was a dream come true: one package that contained the entire saga.

The soundtrack also deserves mention. With licensed tracks from metal heavyweights like Lamb of God and Mastodon, the game doubled down on the headbanging horror aesthetic that had always been at the heart of Splatterhouse. It was the perfect marriage of 80s gore and 2000s metal culture, and it gave the reboot a personality that was impossible to ignore.

From a nostalgic perspective, the 2010 game felt like Splatterhouse reborn in the way we always imagined it as kids: over the top, grotesque, and unapologetic. From an academic perspective, it showed how reboots can function as both homage and preservation, reintroducing a cult series to a new generation while respecting the old.

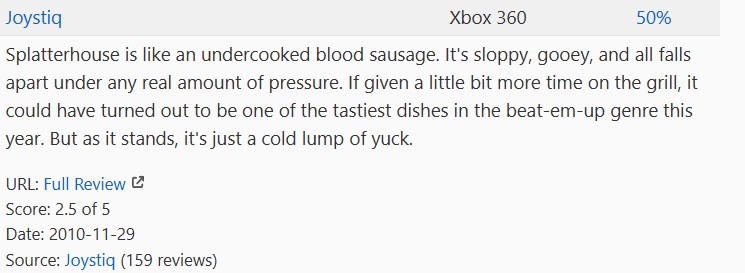

A complicated reception

Critics were divided. Some praised the game’s energy and reverence for its source material. Others criticized technical issues, repetitive combat, and uneven pacing. But for the fans who had waited nearly two decades for a new Splatterhouse, those flaws hardly mattered. The mask was back. The mansion was alive. Rick Taylor was once again smashing monsters to pieces, and we were there with him.

Looking back now, the 2010 reboot occupies a special place in retro gaming history. It was not perfect, but it was heartfelt. It carried the weight of nostalgia while daring to make Splatterhouse something new. And most importantly, it kept the mask grinning long enough for a new generation to discover the series.

2011 to 2025 Reflection, Preservation, and Legacy

When the dust of the 2010 reboot settled, Splatterhouse once again slipped into silence. But this time, the silence felt different. In the late 90s, the series had been dormant because Namco had seemingly moved on. After 2010, fans knew the mask could still rise. The series had proven it could return. And even if the reboot did not sell enough to become a blockbuster franchise, it planted Splatterhouse firmly in the collective memory of retro gaming.

2011 Rise and Fall reflections

In 2011, a longform blog essay titled The Rise and Fall of Splatterhouse circulated through fan communities. It read like an obituary and a love letter at the same time, remembering the highs of the arcade, the quirks of the TurboGrafx 16 port, the daring experiments on Genesis, and the messy road to the reboot. For many readers, this piece captured what we were all feeling: Splatterhouse was not just a video game, it was a moment in time. It was sticky carpet arcades, weekend rentals from Blockbuster, horror VHS tapes smuggled into sleepovers, and those thrilling thuds of Rick’s board hitting home.

That kind of writing is important because it shows how nostalgia and criticism overlap. The author mourned the reboot’s flaws but celebrated the fact that it even existed. And that balance — love mixed with critique — has defined how fans and scholars continue to talk about Splatterhouse today.

2017 Namco Museum and the Switch

For a while, Splatterhouse was once again a memory, but in 2017 it reappeared as part of Namco Museum for the Nintendo Switch. Nestled alongside Pac-Man, Galaga, and Dig Dug, Splatterhouse looked like the rebel of the group, the bad kid hanging out in the corner of the arcade lineup. Seeing it there on a modern Nintendo platform felt surreal. This was the same game that once terrified parents and was banned in certain arcades in 1989, now packaged as part of gaming heritage.

For younger players, Namco Museum was an introduction. For those of us who remembered, it was validation. Splatterhouse was no longer an oddity whispered about in fan circles. It was being recognized as part of the canon of Namco’s most important games.

In 2020 the retro mini console craze reached Splatterhouse when the PC Engine Mini and TurboGrafx 16 Mini were released. Both systems included Splatterhouse as part of their lineups. For players in North America, this was another chance to revisit the red-masked TurboGrafx version. For Japanese fans, the PC Engine Mini offered the slightly more faithful original.

What mattered most was accessibility. Suddenly, Splatterhouse was not just for collectors or emulation enthusiasts. It was plug-and-play. Anyone could bring home a piece of horror history and relive the thrill of guiding Rick through the mansion’s grotesque halls.

2023 The Arcade Archives release

The biggest moment of the modern era came on 06 22 2023, when Hamster added the arcade original to its prestigious Arcade Archives line for Nintendo Switch and PlayStation 4. For purists, this was the Holy Grail. No censorship. No compromises. Just the raw 1988 arcade game, complete with online leaderboards, difficulty options, and display settings that let you tweak the experience for modern screens.

Hamster’s official title listing confirms the release, while Time Extension’s coverage celebrated the return as a major win for retro horror fans. For those of us who remembered slipping quarters into the machine back in the day, playing this version at home felt like stepping into a time machine.

The timing was perfect too. By 2023 retro gaming had gone mainstream. Nostalgia was no longer niche; it was culture. Splatterhouse arriving in pristine form during that wave ensured that its legend would not fade again.

Nostalgic reflection the mask still grins

For players, though, the legacy is more personal. We remember the sticky floors of 1989 arcades, the thrill of sneaking a TurboGrafx rental home in 1991, the desperate fight against the clock in Splatterhouse 3 on a Genesis summer afternoon in 1993. We remember discovering West Mansion in the late 90s and realizing other fans out there were keeping the flame alive. We remember the excitement of reading that Sega-16 interview in 2008 and thinking maybe, just maybe, the mask was coming back. We remember the bittersweet feeling of finally playing the 2010 reboot, flaws and all, and grinning anyway because Rick was smashing monsters again.

And today, in 2025, we can fire up a Switch or a PlayStation, download Arcade Archives Splatterhouse, and feel it all over again. The thud of the board. The green splatter against the wall. The laughter of the mask.

The mask still grins. And as long as fans remember, Splatterhouse will never really die.

With Splatterhouse’s blood-soaked journey fully explored, this feature kicked off our new History of series, where we peel back the layers of gaming’s most fascinating titles. The story doesn’t end here, though. For our second deep dive, we turned our attention to the world of RPGs with Lunar: The Silver Star and its sequel, tracing their remakes, fandom, and legacy. You can read the full article here: History of Lunar: The Silver Star and Eternal Blue.

Retro Replay Retro Replay gaming reviews, news, emulation, geek stuff and more!

Retro Replay Retro Replay gaming reviews, news, emulation, geek stuff and more!