Link Was Christian, and You Cannot Pretend Otherwise

Let’s stop dancing around it. Link was Christian. That is not up for debate. And we are going to cover it all. The original Legend of Zelda on the NES flat-out called one of its items the Bible in Japan. The sprite shows a little book with a cross on the cover. The English manual swapped the name out for “Book of Magic,” but the cross stayed right there on the art. The follow-up, Zelda II: The Adventure of Link, doubled down with an actual item called the Cross. Pick it up, and suddenly invisible enemies like the Moa became visible. Then came A Link to the Past, which made things even clearer. The Japanese version literally calls the Sanctuary a church, the kindly old man inside a priest, and it even makes Link pray, visibly drawing a cross on his chest, to open the Desert Palace. You can argue all day about what Nintendo of America censored, but you cannot argue with what shipped. Link was a Christian hero. Period.

(HEY YOU!! We hope you enjoy! We try not to run ads. So basically, this is a very expensive hobby running this site. Please consider joining us for updates, forums, and more. Network w/ us to make some cash or friends while retro gaming, and you can win some free retro games for posting. Okay, carry on 👍)

You do not have to take my word for it. Legends of Localization shows the Japanese manual page where the Book of Magic is explicitly labeled バイブル, Bible. Zeldapedia’s Christianity entry lays out every early example, from the cross-bearing shields to the official artwork of Link kneeling before a crucifix. And if you want to see how the Cross worked in Zelda II, Triforce Wiki’s Cross page spells it out: without it, the Valley of Death is a nightmare; with it, the unseen is revealed. These are not fan theories. They are the original games.

For those of us who grew up playing these cartridges, the nostalgia is powerful. Sitting on the floor in front of a humming tube TV, holding the NES controller in our hands, we saw Link’s shield with a red cross and never thought twice. It felt natural. A hero would carry a shield like that. A book with a cross looked right at home in a dungeon. And when A Link to the Past asked us to pray in front of a stone tablet, the gesture was familiar. This was not a “fantasy religion.” This was our world bleeding into Hyrule. The fact that Nintendo later swapped out “church” for “sanctuary” and “priest” for “sage” does not erase what we saw.

As one fan once commented under an article on Geeks Under Grace:

“As a long-time Zelda fan and Christian, I always found those hidden influences heartwarming.”

That is the tone right there , warm recognition.

That is the joy of rediscovering what was always there. The crosses, the prayers, the Bible, all hiding in plain sight in some of the most beloved games of our childhood. It is canon, whether you like it or not.

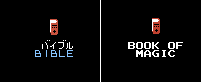

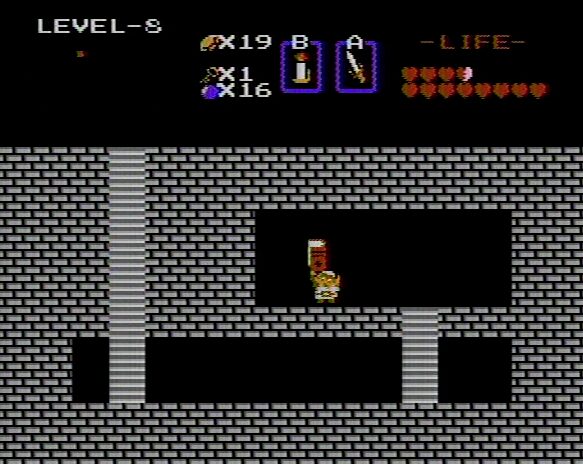

The Bible in Zelda I

When you booted up The Legend of Zelda for the very first time in 1986, you probably did not think you were walking into a theological debate. You were just trying to survive Moblins, collect keys, and figure out what the old man meant by “It’s dangerous to go alone.” But hiding inside that world of pixels was one of the clearest statements about Link’s faith you will ever find. Among the swords, boomerangs, and bombs sat a book. In Japan, that book was not mysterious at all. It was called the Bible.

This is not a nickname cooked up by fans years later. It is right there in the official Japanese manual and item listings. The sprite is a small book with a cross emblazoned on the cover. The Japanese text spells it out as バイブル , literally “Bible.” When the game was localized for North America, Nintendo of America was already tightening the rules about real-world religious references. Out went the word “Bible,” and in came the safer, vaguer term “Book of Magic.” But the cross on the cover never disappeared. If you were an observant kid staring at that tiny pixel art on your CRT, you saw a cross every time. Legends of Localization’s side-by-side comparison proves it beyond question.

The function of the item only makes the point stronger. When you pick up the Bible, your Magic Wand suddenly shoots flames. Nintendo of America might have hoped the new name would nudge players into thinking “grimoire,” but anyone who grew up around church pews knew exactly what that little book with a cross was supposed to be. It was the same book that sat on pulpits and nightstands across the world. That parallel hit differently for Christian kids in the eighties and nineties. The hero of Hyrule carried the same holy book you saw at home on Sunday mornings, and it gave him real power against the darkness. That kind of symbolism was never going to stay hidden forever.

Fans have never stopped rediscovering this little piece of trivia. On Zeldapedia’s page about Christianity in Zelda, you can scroll through a list of early items and see the Bible right at the top, complete with screenshots and references. The site even notes how the design of the book never changed, only the English name. Over on Zelda Dungeon’s page for the Book of Magic, the description repeats the same story, acknowledging that in Japan this was simply the Bible. These are not obscure fan theories hiding in forgotten forums. They are hard-coded facts, backed by art, manuals, and the game itself.

What makes this so fascinating is how matter-of-fact it felt at the time. No one thought Nintendo was secretly preaching a sermon. Kids just accepted it. A book with a cross was an item that helped the hero. In hindsight, that is the perfect example of how faith symbols can sneak into pop culture. They become part of the adventure without feeling out of place. That little book reminded millions of players of something bigger than the dungeon they were exploring. And whether Nintendo of America wanted it or not, the truth slipped through. Link carried the Bible. Link was Christian.

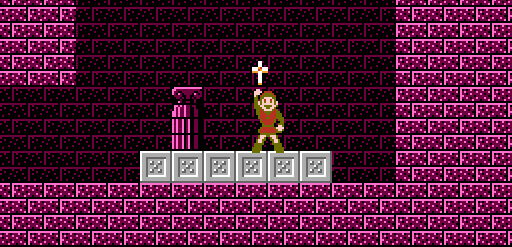

The Cross in Zelda II

If the Bible in the first Zelda was not enough proof, the sequel left no room for doubt. Zelda II: The Adventure of Link introduced a new item simply called the Cross. No euphemisms. No clever translation swap. It was the Cross. And it was not a decorative trinket either. This relic completely changed how you experienced the game. Without it, certain enemies were invisible. With it, the unseen became visible. That is not just good game design. That is a Christian symbol with real weight.

Players from the eighties will remember the nightmare that was the Valley of Death, the stretch you had to cross before reaching the final Great Palace. Invisible Moas, ghostly bird-like enemies, would swoop in and shred your health bar. They would kick your butt without the cross. If you did not have the Cross, there was no way to see them coming. You could technically brute force your way through with raw skill and down stab, but for most players it felt like bashing your head against a wall. The moment you picked up the Cross, though, the game shifted. Suddenly those invisible terrors were exposed. What was once frustration turned into relief. It felt almost biblical , the light of truth revealing what was hidden in darkness. Triforce Wiki’s entry makes this crystal clear: the Cross “enables Link to see Moas and other invisible enemies.”

The symbol itself could not be more blatant. The sprite is a simple cross shape, unmistakable on screen. The manual even spells out the effect in plain text. Zeldapedia’s page on the Cross notes how essential it is to surviving the endgame and how much it ties into the broader Christian imagery of the early series. This is not a rune or an abstract symbol. It is the Cross, the most recognizable image in all of Christianity, functioning as a literal mechanic in a Nintendo game. That is not coincidence. That is design.

Nintendo of America did not rename this one. They left the word Cross right there in the English version, perhaps because by then the policy lines were still being drawn. Either way, the intent comes through loud and clear. In Zelda II, your final march to the Great Palace requires you to bear the Cross. That is canon. That is not interpretation. That is what the game demands of you. And it ties directly back to the larger truth: Link was not just some generic fantasy warrior. He was marked from the beginning with Christian symbols, and the Cross in Zelda II is the most powerful proof yet.

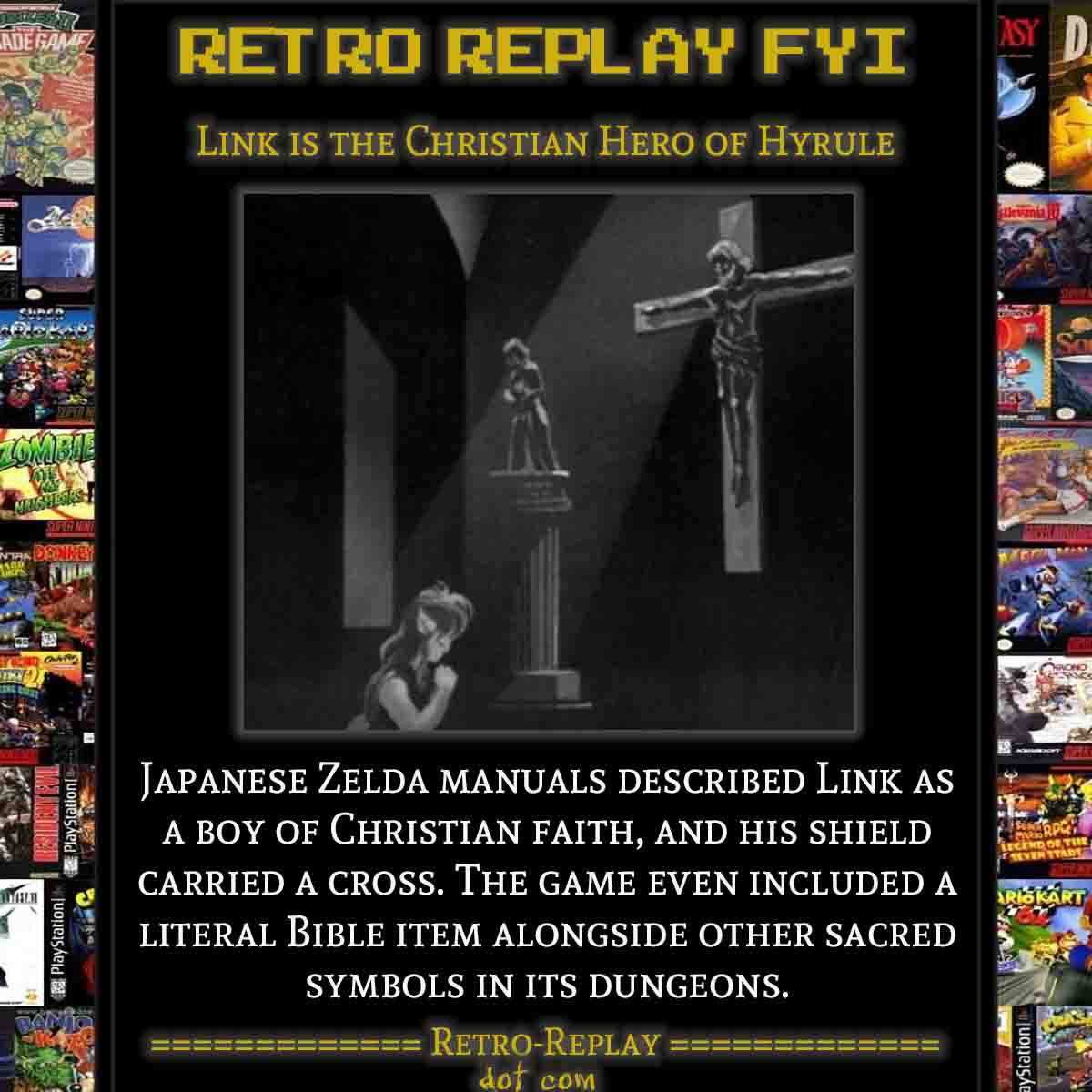

The Church, the Priest, and Link’s Prayer in A Link to the Past

By the time A Link to the Past launched on the Super Nintendo in 1991, the Zelda series had grown more ambitious. Bigger maps, richer lore, more cutscenes, more personality in every dungeon. But tucked inside all that polish were moments that carried forward the Christian imagery from the first two games , this time with even greater clarity. In the Japanese release, the Sanctuary that protects Princess Zelda is not called a sanctuary at all. It is called a church. The old man who watches over her is not a sage. He is a priest. And when Link needs to open the path to the Desert Palace, the game does not ask him to wave a wand or play a tune. It asks him to pray.

The interior looks exactly like a European cathedral, with pews, an altar, and stained glass windows casting colored light across the stone floor. The Japanese manual and dialogue identify it plainly as a 教会 , a church. Zelda Wiki’s page on the Sanctuary confirms that the Japanese name is “Church” and that the attendant is a priest. In English, Nintendo changed these to “Sanctuary” and “sage,” but the visuals never changed. Anyone who walked into that building as a child felt it instantly. This was not a vague “temple.” This was a church, just like the one you passed on the corner every Sunday.

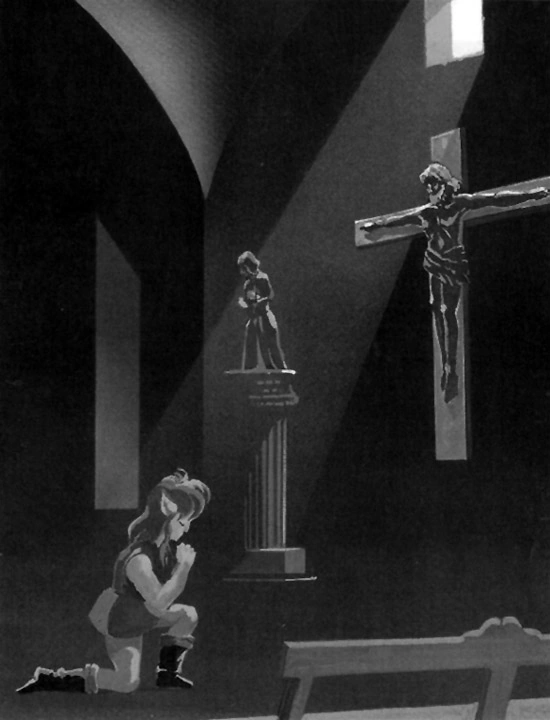

And then there is the artwork. Among the official illustrations for A Link to the Past is a striking image of Link kneeling in prayer before a crucifix. Fans have traded scans of this piece for years, and it still pops up on sites like Reddit whenever someone rediscovers it. One thread on r/gaming included comments like “How did I never know this existed?” and “This makes me love Link even more.” Whether it was concept art, promotional art, or tucked in certain manuals, the point remains the same. Nintendo themselves once put the hero of Hyrule in front of a crucifix. That is not subtext. That is text. See an example of the circulated artwork here.

For players who grew up in the early nineties, these details made a deep impression. Walking into the Sanctuary felt like stepping into something holy. Hearing the music shift to an organ-like theme reinforced it. Watching Link pray to open a dungeon was unforgettable. Decades later, fans still recall those moments as proof that the series was once unafraid of overt Christian imagery. Nintendo of America might have changed words, but the truth slipped through again. Link prayed. He prayed in a church, under the guidance of a priest, and that scene is etched into gaming history.

This piece of art has taken on almost mythic status among fans because it was not as widely circulated in North America. For many players, the first time they see it is when it resurfaces on forums, blogs, or social media threads. A Reddit post on r/gaming sparked one of those rediscoveries, with comments pouring in like,

“Jesus is cannon.”

and

“The reason I loved Zelda 2 was because the art depicts Link as a sort of Crusader with some catholic symbology. It reminded me of Castlevania in a way. I have always had a thing for that sort of “holy warrior of light walking into the darkness” style. I played a Paladin in WoW because of that, so yeah, this image feels right to me!”

It is one thing to see a cross on a shield in an eight-bit sprite. It is another to see the protagonist of a legendary franchise drawn in solemn reverence before a crucifix.

What makes this artwork so powerful is how well it aligns with what the game itself depicts. The Sanctuary looks like a cathedral. Link is asked to pray to open the Desert Palace. The Japanese text calls the cleric a priest. The art ties all of these elements together in a single iconic image. It is as if Nintendo was saying, “Yes, this is the heart of the character.” For Christian players, this was more than trivia. It was a moment of recognition, a reminder that faith symbols could sit right alongside swords and sorcery without feeling out of place.

Even those who are not religious still feel the weight of it. Articles like HubPages’ overview of Christianity in Zelda point to this illustration as the clearest example of how much the early series leaned into Christian imagery. Bloggers, fan archivists, and wiki editors all use it as a centerpiece because it is visual proof that cannot be hand-waved away. You can argue over translation choices. You can debate the meaning of a sprite. But a crucifix on official Nintendo artwork is undeniable. Link kneels before the cross. That is canon.

For players who grew up seeing this art in a magazine clipping or manual insert, the nostalgia is electric. The memory of flipping through a glossy page and suddenly realizing your favorite hero was shown in such a holy moment is the kind of thing that sticks with you for life. That feeling is why this image continues to circulate decades later, inspiring awe, surprise, and pride. It is not subtext, it is not fanfic, it is not headcanon. It is the official record.

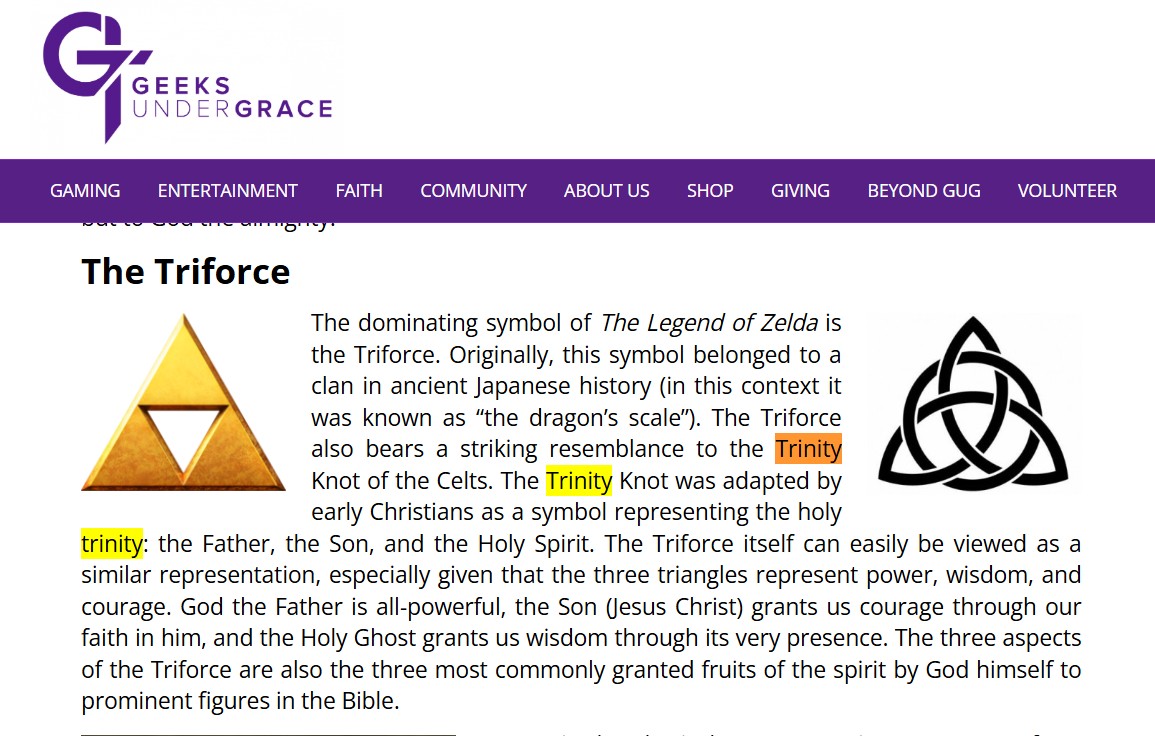

The Triforce and the Trinity

By the time A Link to the Past had settled into its place as the definitive Zelda adventure of the early nineties, players were already familiar with the series’ ultimate relic: the Triforce. Three golden triangles bound together as one, each piece representing a distinct virtue , Power, Wisdom, and Courage. To kids at the time, it was a simple visual hook. Three pieces of a puzzle that made Link stronger and defined the fate of Hyrule. But for anyone who grew up in a Christian household, the parallel was impossible to ignore. Three distinct pieces forming one whole is not just good game design. It is a mirror of the Trinity.

This does not mean Shigeru Miyamoto or Takashi Tezuka set out to catechize players with theology. But symbols have a way of carrying resonance beyond their intended use. Medieval manuscripts are filled with diagrams of the Shield of the Trinity, showing three nodes labeled Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, connected by lines that declare each is God yet distinct from one another. Now put that next to the Triforce, where three distinct virtues combine into a single force that holds Hyrule together. For Christians, the echo is obvious. And even if Nintendo never made the connection out loud, it is one more reason the early series felt steeped in something familiar and holy.

Writers and fans have been calling out this parallel for decades. The Christian gaming site Geeks Under Grace went so far as to say that the Triforce’s virtues “sit comfortably with Christian virtue language,” making Link’s quest resonate with themes of faith whether Nintendo intended it or not. Meanwhile, long retrospectives like HubPages’ essay on Christianity in Zelda tie the Triforce to medieval Christian imagery because the resemblance is too strong to pass over. Even secular fans admit that the “three-in-one” motif calls something bigger to mind.

What makes this connection even richer is how Link embodies those virtues in a way that looks a lot like a life of faith. He shows Courage by risking everything to defend the innocent. He shows Wisdom by listening to guidance from elders and sages. He wields Power not to dominate but to serve. That balance reflects the Christian vision of virtue as something given by God and lived out in action. For many players, even if they never articulated it as kids, the Triforce felt like a kind of spiritual truth in pixel form. It was not just treasure. It was a symbol of order, harmony, and divine unity.

Nintendo of America’s Censorship

By the early nineties, Nintendo of America had started to enforce a strict set of content guidelines. These rules were designed to avoid anything that could stir up controversy in the United States. That meant no nudity, no gore, and , most relevant to Zelda , no overt religious symbols. Crosses, Bibles, priests, and churches were all suddenly off-limits. The irony is that the games were already shipping with these elements baked in. What followed was a scramble to sand down the obvious references while leaving the sprites, artwork, and core mechanics mostly intact.

Of course, fans noticed. Even as kids, players knew they were standing in a church. They saw pews and stained glass. They heard organ-like music. They knew what prayer looked like when Link bowed his head. The censorship created a strange disconnect, where the art screamed “church” but the manual whispered “sanctuary.” On forums, blogs, and even in casual conversation, that odd tension has stuck with fans for decades. As one Reddit commenter once put it, “Nintendo can call it whatever they want, but my childhood brain knew exactly what I was looking at.” And they were right. The truth of Zelda’s Christian imagery slipped past the red pen and made its way into the hands of millions.

How Later Zelda Games Echoed the Early Christian Roots

By the time Ocarina of Time launched in 1998, Nintendo had all but erased direct Christian imagery from Zelda. The Triforce had fully become the symbol of Hyrule’s fictional goddesses, and the priests and churches were replaced with sages and temples. Yet even in this new mythos, the fingerprints of Christianity never quite disappeared. Instead, they resurfaced as echoes, woven into story beats, symbols, and moments that felt strangely familiar to players who grew up in Christian households.

Take the Temple of Time. On paper, it was just a grand building that housed the Master Sword. But its vaulted ceiling, stained glass-like windows, and sense of holy reverence gave it the feel of a cathedral. Fans have long noted its resemblance to real-world Christian churches, from its architecture to its function as a sacred place of protection and transformation. The Geeks Under Grace article on finding God in Hyrule draws a direct line between the Temple of Time and Christian houses of worship, noting how players instinctively understood its sacred purpose because it looked and felt like a church.

Another echo appears in Wind Waker. The story is drenched in flood imagery, with Hyrule submerged beneath the sea. Christian readers immediately recognized the parallel with Noah’s Ark , a world washed away, a chosen remnant surviving on the waters, and a new world waiting to be reborn. Writers at More Than Entertained even suggested that Zelda’s flood imagery may have been Nintendo’s quiet way of holding on to its Biblical inspirations while filtering them through mythology. It was less overt than Link kneeling before a crucifix, but the echoes were clear enough for those who knew the stories.

Even characters began to carry these resonances. Zelda herself, especially in Skyward Sword, took on an almost incarnational role. As the msaundersped deep dive points out, Zelda is literally the goddess Hylia reborn as a human, sacrificing her divinity to live among her people. Christian players could not help but notice how close this sat to the Incarnation itself. It was not exact, of course, but it felt like an echo, a whisper of a larger truth repackaged for a fantasy audience.

The point is that even after Nintendo of America’s policies stripped away the overt symbols, the DNA of Zelda still carried Christianity within it. Architecture, floods, trinities, and incarnations all wove together into a tapestry that fans could recognize without needing it spelled out. Link may not have been praying before a crucifix anymore, but the stories still sounded familiar, the imagery still rang true, and the echoes of faith kept resonating long after the official policy tried to silence them.

The Fan Community and the Fight to Preserve Zelda’s Christian Identity

If Nintendo thought they could quietly erase Christianity from Zelda with a few localization policies, they underestimated the fandom. Players noticed. Parents noticed. And in the age of the internet, fans became archivists, detectives, and evangelists for Zelda’s lost faith.

Websites like Zelda Archive and personal projects such as Michael Saunders’ detailed blog on Zelda’s Christian imagery began compiling every scrap of evidence. Screenshots of crosses on Link’s shield, scans of instruction manuals showing him kneeling in prayer, and side-by-side comparisons of Japanese versus American releases became the fuel for an underground movement determined to prove what so many suspected: that Link was originally written as a Christian hero.

Link’s Faith is Canon, Whether You Like It or Not

From the first cross etched on Link’s shield to the Bible hidden in the Japanese release, the evidence is overwhelming. Early Zelda was not shy about its Christian DNA. Nintendo of America may have tried to smudge it out with localization tricks and careful censorship, but the art, the sprites, the manuals, and the memories of millions of players tell the real story. Link was written as a Christian hero.

For those of us who grew up with these games, this revelation is more than trivia. It feels like a confirmation of what we always sensed as kids, staring at those glowing CRT screens late at night. Zelda was not just another fantasy. It carried echoes of our own faith, our own history, our own symbols of light versus darkness. It mattered then, and it matters now.

The fandom has preserved this truth with the same determination that Link himself shows in every quest. Through wikis, scanned manuals, forum debates, and countless nostalgic conversations, the story has survived. You can read it plainly in resources like Zelda Archive’s Christianity entry, or dive into the commentary at places like Geeks Under Grace and Ganker. You can even see it in the official art that shows Link kneeling before a crucifix, an image that has circled the internet for decades because it cannot be erased.

So here is the final word: Link’s Christianity is not speculation. It is canon, sealed into the pixels of the NES and the text of the Japanese manuals. You can deny it, you can ignore it, you can even laugh at it, but the truth remains. The Hero of Time was a Christian knight, a crusader against evil, a character whose courage was rooted in faith. And that is something worth remembering every time we pick up the controller, whether in 1986 or 2025.

Just don’t get me started on this image of Peach holding up a crucifix to ward off a Hammer Bro.

Retro Replay Retro Replay gaming reviews, news, emulation, geek stuff and more!

Retro Replay Retro Replay gaming reviews, news, emulation, geek stuff and more!

Funny how in a mostly Christian nation that needed to be removed.

Originally, his shield had a cross on it. And the magic book was called a Bible. I’ve always experienced a holiness from the franchise.