Rip and Tear: The Definitive History of the Original DOOM

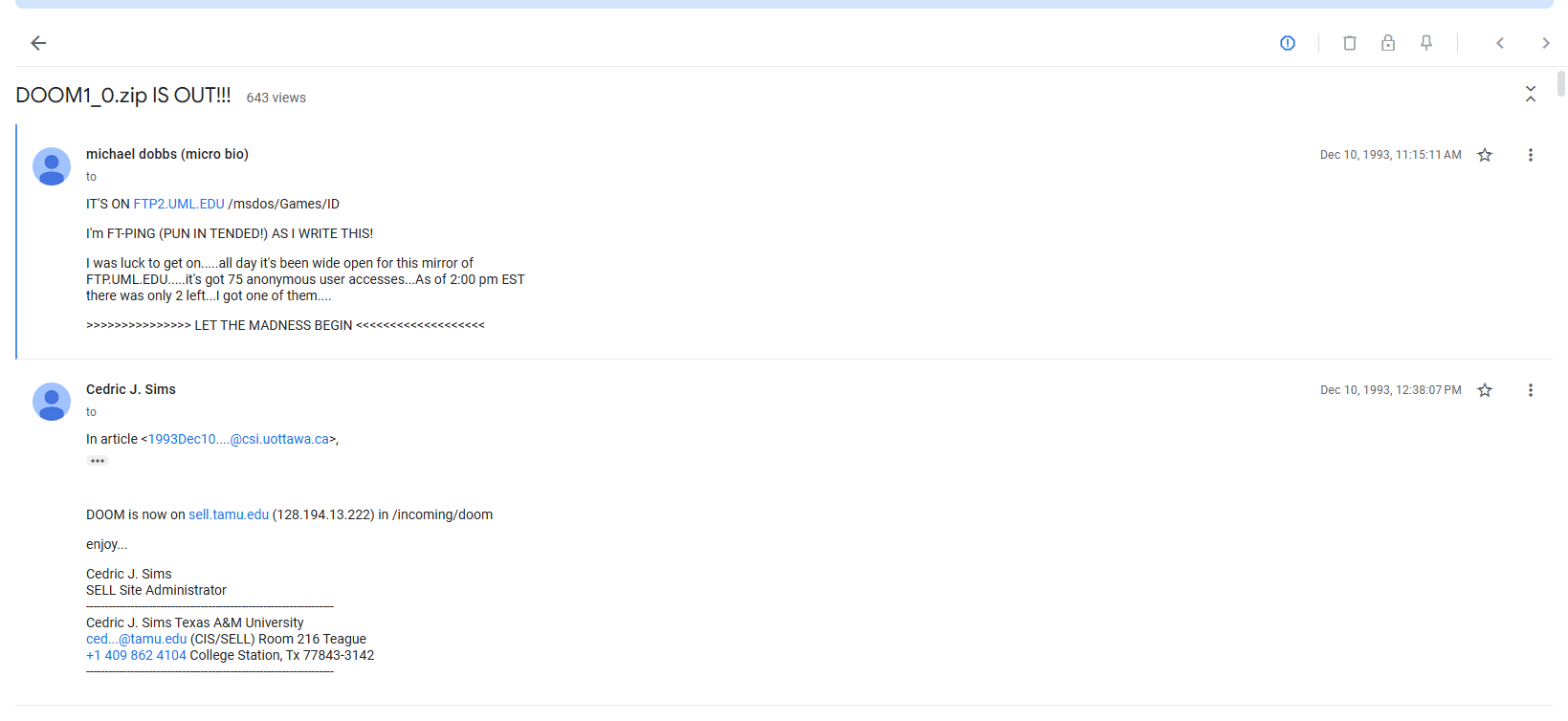

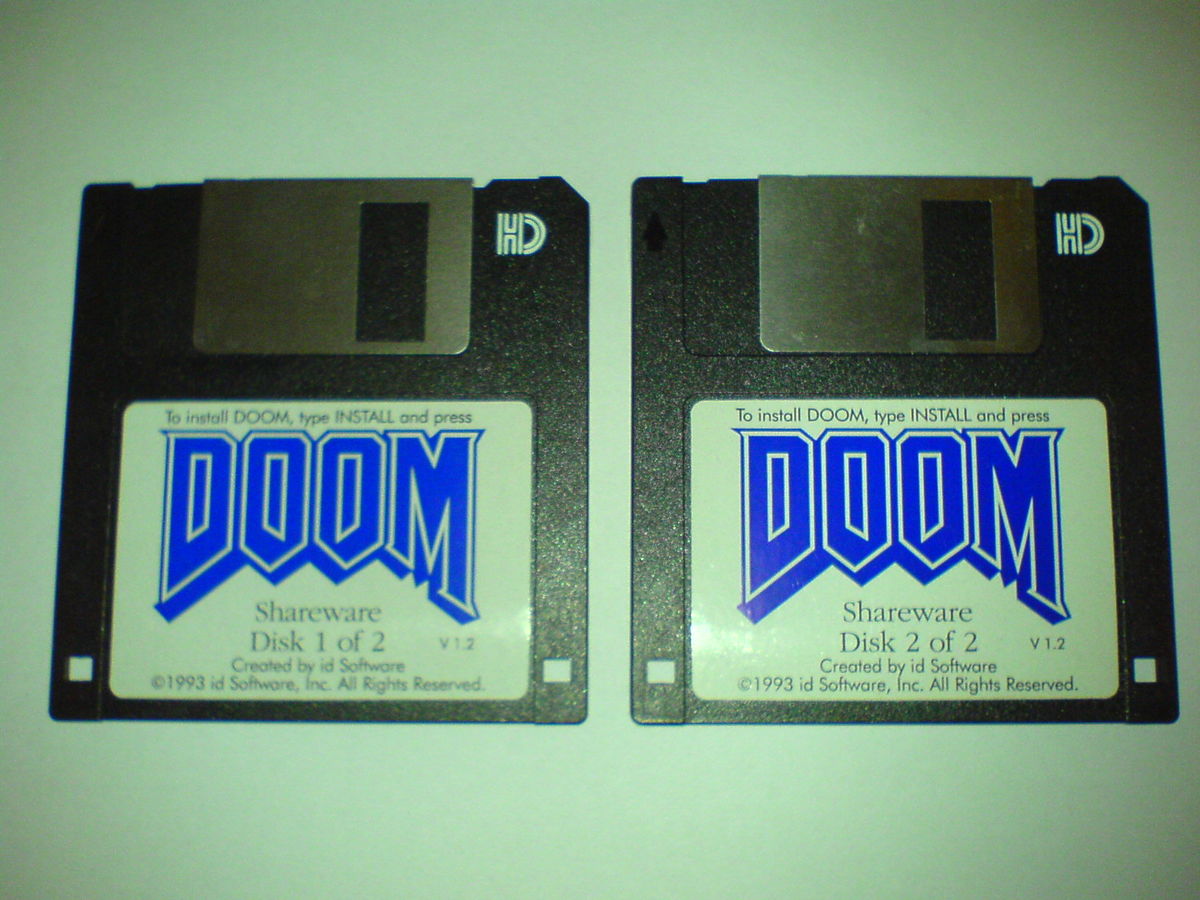

On December 10, 1993, a file named DOOM1_0.ZIP was uploaded to an FTP server at the University of Wisconsin. There was no multi-million dollar marketing campaign, no flashy Super Bowl commercial, and no coordinated launch event. There was only a 2.39 MB compressed file, unleashed onto the nascent internet and the sprawling network of Bulletin Board Systems (BBS).

(HEY YOU!! We hope you enjoy! We try not to run ads. So basically, this is a very expensive hobby running this site. Please consider joining us for updates, forums, and more. Network w/ us to make some cash or friends while retro gaming, and you can win some free retro games for posting. Okay, carry on 👍)

What happened next wasn’t just the release of a video game. It was a shockwave.

Across North America, university and office networks—the very arteries of the early internet—began to slow, choke, and seize. System administrators, baffled by the sudden, massive spike in traffic, dug into their logs. They all found the same culprit: DOOM1_0.ZIP. The game’s network play, a feature called “deathmatch,” was so popular that companies like Intel and Texas A&M had to implement specific policies banning it during work hours.

That 2.39 MB file contained the first shareware episode of DOOM, the magnum opus of a small, rebellious team of developers in Mesquite, Texas, calling themselves id Software. Within months, it was estimated that Doom was installed on more computers worldwide than Microsoft’s new Windows 95 operating system.

It was a technological marvel, a cultural lightning rod, and the bloody, pixelated birth of the first-person shooter genre as we know it today. This is the story of how a handful of long-haired misfits, fueled by pizza, Dungeons & Dragons, and heavy metal, built Hell on Earth and, in doing so, changed the world forever.

Chapter 1: The id Supergroup – From Softdisk to Stardom

The story of Doom begins not in a high-tech lab, but in the humid, unassuming offices of Softdisk, a “disk magazine” company in Shreveport, Louisiana. In the late 1980s, Softdisk operated on a subscription model, mailing out floppy disks with a collection of new programs each month. Working in its “Gamer’s Edge” division, often in a cramped, windowless office, was a group of young, prodigiously talented, and deeply ambitious developers.

They were the core that would become id Software (Source):

- John Carmack (The Wizard): The technical genius. A quiet, intensely focused programmer from Kansas City, Carmack was a force of nature. After a brush with the law as a teen that landed him in a juvenile home (where he reportedly told a psychologist, “if I don’t get to a computer soon, I’m going to die”), he was singularly obsessed with one thing: speed. He didn’t just write code; he architected graphical realities that no one else thought possible on the limited hardware of the day.

- John Romero (The Rockstar): The design and marketing force. Charismatic, energetic, and with a flair for the dramatic, Romero was the yin to Carmack’s yang. He had been designing and selling his own games since he was a teenager. He had an intuitive, almost primal understanding of what made a game fun—the “feel,” the pacing, the feedback loop of action and reward.

- Tom Hall (The Storyteller): The creative director and ideas man. Hall was the organizational force, the D&D Dungeon Master, the one passionate about building worlds, characters, and narratives. His whimsical, creative energy was the driving force behind id’s first major hit, Commander Keen.

- Adrian Carmack (The Artist): The visual architect (no relation to John). A quiet artist who had joined Softdisk, Adrian’s style was dark, grotesque, and heavily influenced by the art of H.R. Giger, horror films, and heavy metal album covers. He was not a programmer, but a traditional artist who found his calling in the digital medium, translating his unsettling visions into 16-color pixel art (Source).

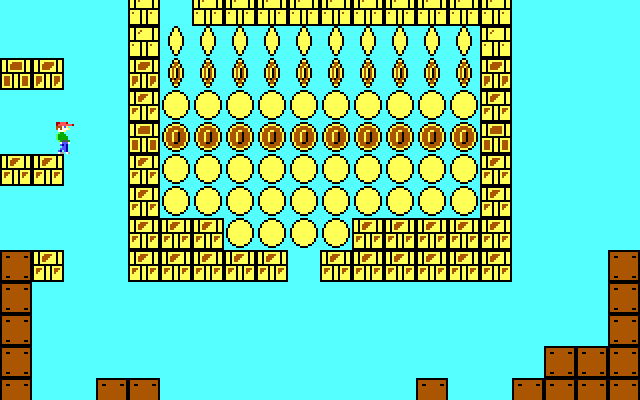

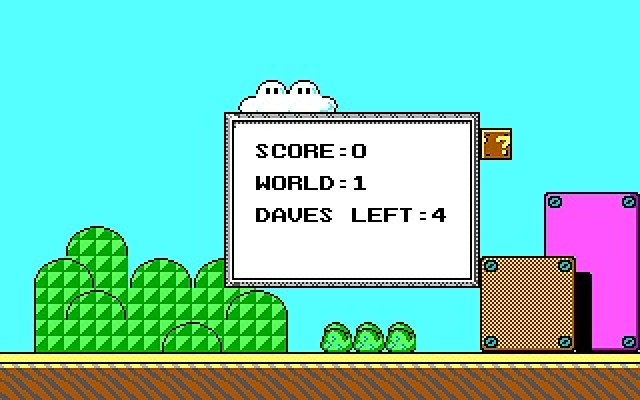

The catalyst for their departure was a single, groundbreaking technical discovery in 1990. One night, John Carmack, inspired by the smooth-scrolling backgrounds of Super Mario Bros. 3 on the NES, had a breakthrough. He figured out how to replicate the effect on a standard PC’s EGA graphics card—something widely believed to be impossible. He and Tom Hall stayed late, and in a matter of hours, they had recreated the first level of Mario 3, with Romero’s Dangerous Dave character sprite in place of Mario.

They called it Dangerous Dave in Copyright Infringement.

When Romero saw the demo the next morning, he immediately grasped its significance. This wasn’t just a tech demo; it was their ticket out. They now possessed a technology that their employer, Softdisk, was too slow to capitalize on, but that a new, nimble company called Apogee Software, run by Scott Miller, would know exactly what to do with.

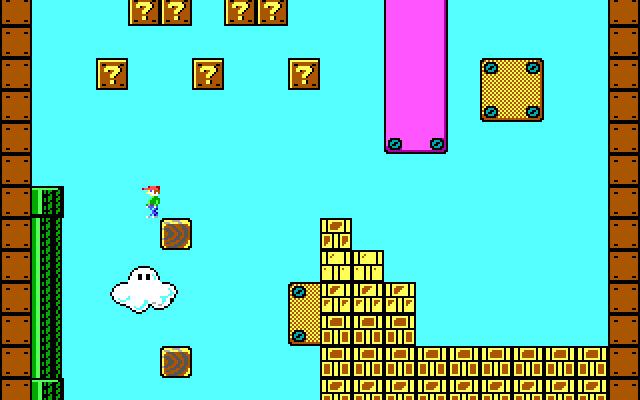

Using company computers on nights and weekends, the team—calling themselves “Ideas from the Deep”—built a full game around Carmack’s engine: Commander Keen. They sent it to Miller at Apogee, who, recognizing its brilliance, pioneered the “shareware” model with it. The first episode was released for free, turning players into evangelists, while the full trilogy was sold via mail order.

The first royalty check from Commander Keen was for over $10,000—more than they made in months at Softdisk (Source). The path was clear. On February 1, 1991, the four founders officially resigned from Softdisk and formed id Software. The name, suggested by Romero, was short for “in demand,” but also referenced the Freudian concept of the “id”—the primal, instinctual, aggressive part of the mind. It was a fitting name for a company that would soon unleash the most primal game the world had ever seen.

Chapter 2: The Third Dimension Beckons – From Catacomb to Wolfenstein

Id’s first year was a blur of Keen sequels, but John Carmack was already bored. 2D scrolling was a solved problem. The next frontier was the third dimension.

His first experiments were Hovertank 3D (1991) and Catacomb 3-D (1991). These games were primitive, with flat, solid-color walls, but they were fast, and they were in first-person. Catacomb 3-D was particularly notable: it was the first time a player’s hand and weapon were drawn on-screen, creating a tangible sense of presence.

The team knew this was the future. They decided to build their next full game around this 3D concept, licensing the name of a classic 1981 stealth game: Castle Wolfenstein.

Released in May 1992, Wolfenstein 3D was a cultural phenomenon. It wasn’t the first-ever 3D game, or even the first FPS, but it was the one that broke through. It was fast, violent, and viscerally thrilling. For the first time, players felt the rush of inhabiting a 3D game world. Its shareware release made id Software a household name among PC gamers and earned them a fortune.

But Wolfenstein was, by Carmack’s standards, a technological hack. The world was a flat grid. All walls were at 90-degree angles. Floors and ceilings were untextured, unlit voids. There was no concept of “up” or “down.” It was a “raycaster” engine, which essentially drew a 2D map and extruded it up, like a maze.

Even as Wolfenstein 3D was flying off the virtual shelves, Carmack was already deep in his NeXT computer workstation, a powerful and (at the time) expensive machine that offered a superior development environment. He was writing the successor to the Wolfenstein engine. This new engine would be a quantum leap forward. It would have:

- Textured floors and ceilings.

- Walls at any angle, not just 90 degrees.

- Variable floor and ceiling heights, allowing for stairs, platforms, and pits.

- Variable lighting, allowing for pitch-black rooms and flickering strobes.

He was building the engine that would power Doom. The team, now flush with cash, began brainstorming. Their next game, they decided, would be a collision of their favorite inspirations: the sci-fi horror of the movie Aliens and the demonic, over-the-top camp of Evil Dead II.

Chapter 3: Forging Hellfire – The DOOM Engine (id Tech 1)

The leap from Wolfenstein 3D to Doom was one of the most significant technological advancements in the history of gaming. The Doom engine (later id Tech 1) was a masterpiece of programming ingenuity, a collection of brilliant hacks that created a convincing illusion of a 3D world on hardware that was barely capable of it (Source).

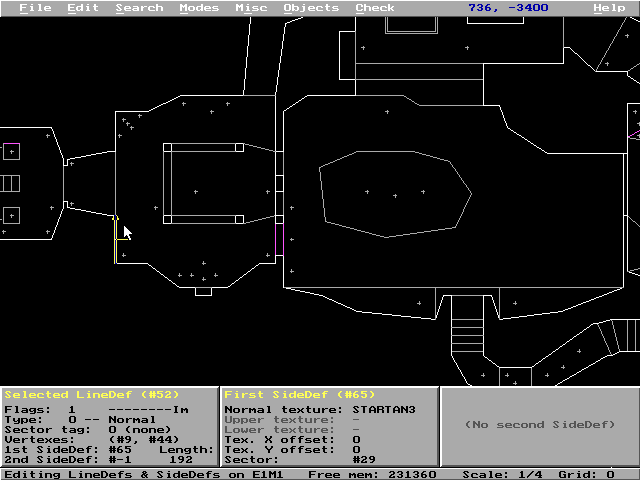

It’s crucial to understand that Doom was not “true” 3D. It was “2.5D.” The levels were drawn as 2D maps, and the engine extruded that map vertically. This is why you could never have a room “over” another room, and why you couldn’t truly look up and down (the engine simply shifted the player’s view vertically, a trick called y-shearing).

But what it could do was revolutionary:

- Binary Space Partitioning (BSP): This was Carmack’s secret sauce for speed. Before a level was played, the Doom map compiler would run, slicing the 2D map into a “tree” of convex sub-sectors. When you were in the game, the engine would instantly know your position in this “tree.” It could then render the level from front-to-back, only drawing the surfaces it knew were visible from your exact spot. This was profoundly efficient and the key to Doom’s buttery-smooth performance, even on a 386 PC (Source).

- Sector-Based Design: The 2D map was made of “sectors.” Each sector was a polygon that had its own properties: a floor height, a ceiling height, a texture for each, and a light level. By changing these properties, doors could “rise” (just changing the sector’s ceiling height), platforms could “lift” (changing the floor height), and lights could “flicker” (changing the light level). This simple, robust system gave birth to all of Doom’s dynamic environments.

- 2D Sprites, 8 Angles: The enemies, weapons, and items in Doom were not 3D models. They were 2D bitmaps, or “sprites.” To create the 3D illusion, the artists created 8 different drawings for each monster—one for each direction (front, front-right, right, back-right, etc.). The engine would simply detect the player’s angle relative to the monster and show the correct sprite. It was a brilliant, performance-saving cheat.

- The NeXT Development Environment: The game was famously not developed on PCs. Carmack, Romero, and the others worked on NeXT workstations, computers made by Steve Jobs’s post-Apple company. These machines ran the NeXTSTEP OS, which was Unix-based, powerful, and featured an advanced programming language (Objective-C). This allowed the team to build their map editor (“DoomEd”) and other tools far more quickly and robustly than they could have on MS-DOS.

- Networking (Dave Taylor’s Contribution): While Carmack built the core engine, id hired programmer Dave D. Taylor, who wrote much of the “spackle code”—the status bar, the automap, and, most critically, the networking. The game’s multiplayer worked on a peer-to-peer model over a LAN, broadcasting small packets of data. It was efficient, fast, and would prove to be one of the game’s most defining features.

Carmack’s engine was a dark canvas of immense potential. Now, the rest of the team had to decide what to paint on it.

Chapter 4: The Art of Damnation – Design, Demons, and Sound

The initial concept, heavily pushed by Tom Hall, was a complex sci-fi epic. The team had even pursued the official Aliens license, but 20th Century Fox wanted too much control (and money), so they decided to create their own universe.

The Doom Bible and a Clash of Visions

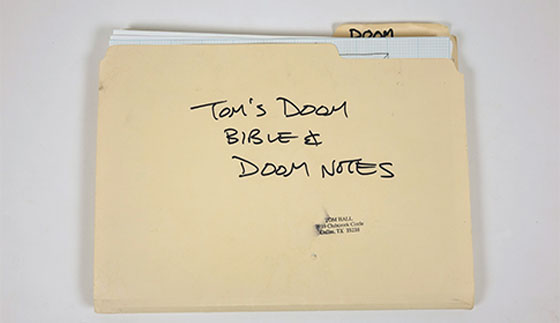

Tom Hall, as creative director, drafted an elaborate, 50-page design document that came to be known as the “Doom Bible” (Source). It detailed a complex storyline set on a military base on a planet called Tei Tenga, complete with five player characters (including one named “Buddy Dacote”), intricate plot points, NPC interactions, and a more realistic, grounded setting.

But a creative rift was forming. Carmack’s engine was abstract, fast, and brutal. Romero, seeing its potential, began designing levels that were fantastical, almost “game-y,” focusing on flow, exciting combat, and intricate layouts. He found Hall’s commitment to realism and story to be constraining and, frankly, boring.

The conflict came to a head. Romero and Carmack argued that the story was secondary. Carmack famously quipped that “story in a game is like story in a porn film; it’s expected to be there, but it’s not that important.” The game didn’t need a complex plot; it needed action. Romero built the first level, “Hangar” (E1M1), as a proof-of-concept for his design philosophy, and the rest of the team agreed: this was the direction.

In the summer of 1993, Tom Hall was forced to resign. It was a painful but pivotal moment that solidified Doom’s core identity: gameplay first, everything else a distant second (Source).

Level Design: Romero vs. Petersen

John Romero took the lead, crafting the entirety of the game’s iconic first episode, “Knee-Deep in the Dead.” His design philosophy, honed over years, was now legendary:

- Flow: Levels should have a logical, intuitive path, even when they’re non-linear.

- Landmarks: Use unique architecture so the player can navigate by sight.

- Contrast: Use light and shadow, and cramped and open spaces, to guide the player and create tension.

- Secrets: Reward exploration. Lots of it.

With Hall gone and the deadline looming, id needed another level designer—fast. They hired Sandy Petersen, a veteran of the tabletop RPG world, famous for his work on Call of Cthulhu. Petersen was a devout Mormon, which the team found amusing, but he had zero qualms about designing hellscapes.

Petersen’s design style was markedly different. Where Romero’s levels were often elegant and interconnected, Petersen’s were chaotic, brutal, and “organic.” He designed most of episodes two (“The Shores of Hell”) and three (“Inferno”). His levels are often more difficult and less forgiving, full of traps and “gotcha” moments. This combination of Romero’s flow and Petersen’s chaos gave Doom its varied, escalating challenge (Source).

Adrian Carmack and Kevin Cloud (another artist at id) were responsible for the game’s unforgettable visual identity. The demons of Doom are icons: the lumbering pink Demon, the fireball-throwing Imp, the floating, one-eyed Cacodemon.

Many of these creatures were not drawn from scratch. Instead, id hired Gregor Punchatz, a practical effects artist, to build physical models (maquettes) out of clay and latex. The Baron of Hell, the Spider Mastermind, and the Cyberdemon were all real-world sculptures. These models were then photographed from 8 different angles, digitized, and touched up by the artists to become the game’s sprites. This technique gave the monsters a tangible, uniquely unsettling quality.

Sound and Music: The Heavy Metal Connection

The final piece was the soundscape by Bobby Prince. The sound effects are seared into the memory of every player: the guttural roar of the Imp, the satisfying pump-action of the shotgun, the squelch of a demon exploding into “gibs.”

And then there was the music. Limited by the MIDI technology of the era, Prince composed a soundtrack that was an unapologetic tribute to the team’s favorite bands: heavy metal and thrash. The connections are blatant and glorious (Source):

- “At Doom’s Gate” (E1M1) is heavily inspired by Metallica’s “No Remorse.”

- “Suspense” (E1M3) draws from Pantera’s “Mouth for War.”

- “Deep Into the Code” (E1M5) is a clear nod to Slayer’s “South of Heaven.”

The music wasn’t just background noise; it was an essential part of the experience, a relentless audio assault that perfectly matched the on-screen carnage.

Chapter 5: The Shareware Gospel – A Revolution in Distribution

The technology was groundbreaking and the design was inspired, but what truly propelled Doom into the stratosphere was its distribution. Id Software, continuing their successful relationship with Apogee’s Scott Miller, embraced the shareware model.

The concept was simple but brilliant: give the first part of the game away for free (Source).

The entire first episode, “Knee-Deep in the Dead,” consisting of nine sprawling levels, was released as the free shareware version. Anyone could download it, copy it, and share it with their friends. There were no restrictions. This model achieved several things:

- It Bypassed Traditional Retail: Id didn’t need a publisher to convince stores to stock their game. They went directly to the consumer.

- It Created Unprecedented Word-of-Mouth: By making the game free, they turned every player into a potential evangelist.

- It Was the Ultimate Demo: The first episode was so substantial and so addictive that it acted as an irresistible advertisement for the full game. After players finished the shareware, a screen would pop up with instructions on how to order the full three-episode registered version for $40 (Source).

The release on December 10, 1993, was an event. The file was uploaded to the University of Wisconsin-Parkside’s FTP server, a major hub. The server, and many others, immediately buckled under the strain. It’s estimated that in its first two years, Doom was played by 15-20 million people, a staggering number for the time. Id Software was soon processing thousands of mail orders a day, raking in over $100,000 daily.

Chapter 6: The Devil’s Playground – Deathmatch, Modding, and DWANGO

Doom wasn’t just a single-player experience. Buried in its code were two features that would ensure its immortality: multiplayer and moddability.

The Birth of Deathmatch

The game supported up to four players over a Local Area Network (LAN). Players could play cooperatively or, more popularly, against each other in a mode the id team christened “deathmatch.”

The term, and the mode itself, became an instant cultural fixture (Source). The concept of the “LAN party,” where gamers would haul their bulky CRT monitors and tower PCs to a central location, was born. Doom deathmatch was fast, brutal, and fiercely competitive. It was the genesis of online competitive gaming as we know it.

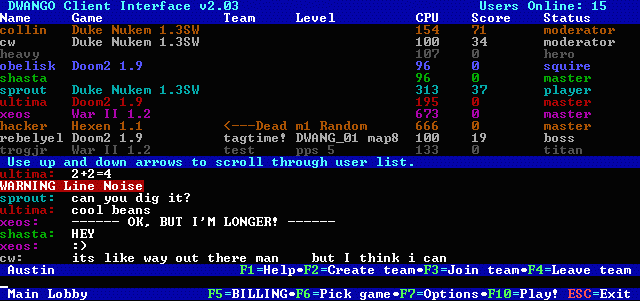

The game’s networking wasn’t designed for the slow dial-up internet of 1993, but that didn’t stop people. A service called DWANGO (Dial-up Wide-Area Network Game Operation) was founded in 1994 specifically to allow people to play Doom over their modems. It was the first major online matchmaking service, a direct precursor to Xbox Live and Steam.

Modding and the WAD Community

Doom’s other, perhaps greater, legacy was its openness. Carmack and Romero intentionally designed the game so that all of its data—the maps, sprites, textures, and sounds—were stored in a single file type with a .WAD extension (“Where’s All the Data?”).

The game engine (doom.exe) was a separate entity that simply read the data from the WAD file. This was revolutionary. It meant that fans could create their own WAD files with custom levels, new monsters, and different sounds, without ever touching the core game code.

An enormous and passionate modding community sprang up overnight. Fans reverse-engineered the file formats and created their own map editors, like DEU (Doom Editing Utility). They began releasing their own custom levels, then full-episode replacements, then “total conversions” that turned Doom into a completely different game (such as the famous Alien TC or a Star Wars mod).

This user-generated content, all available for free, kept the game fresh and alive for decades. It fostered a generation of aspiring game designers—many of whom would go on to become professionals—and established a symbiotic relationship between developers and their fan community that is now a cornerstone of PC gaming (Source). It also gave birth to “speedrunning,” as players competed to beat levels in the fastest possible time, a feature Romero had encouraged by including “par times” in the level data.

Chapter 7: Cultural Impact and “The Doom Clone”

Doom was more than a game; it was a cultural event. It was the “killer app” for PCs, proving that the platform wasn’t just for spreadsheets and word processing.

- Microsoft and Windows 95: Bill Gates was so aware of Doom’s cultural dominance that he considered buying id Software. Instead, he commissioned a port of Doom for the upcoming Windows 95 operating system to prove its gaming capabilities. This port was led by a young Microsoft employee named Gabe Newell, who would later co-found Valve and create Steam. Microsoft even featured Bill Gates in a promotional video where he was digitally inserted into the game.

- The “Doom Clone”: For years, the first-person shooter genre wasn’t called “FPS.” It was called the “Doom clone.” The game established the fundamental mechanics, control schemes, and design tropes that would define the genre for a decade. Games like Dark Forces (a Star Wars “Doom clone”) and Duke Nukem 3D all built upon the foundation Doom had laid.

- Pop Culture Saturation: The game appeared in TV shows like ER and Friends and was referenced in the film Grosse Pointe Blank (Source). The pixelated, bloody violence and demonic imagery became an instant, recognizable shorthand for “video game.”

But with this unprecedented popularity came intense scrutiny. The game’s graphic violence—its “gibs” (short for giblets)—combined with its overt use of satanic imagery, made it a prime target for a moral panic.

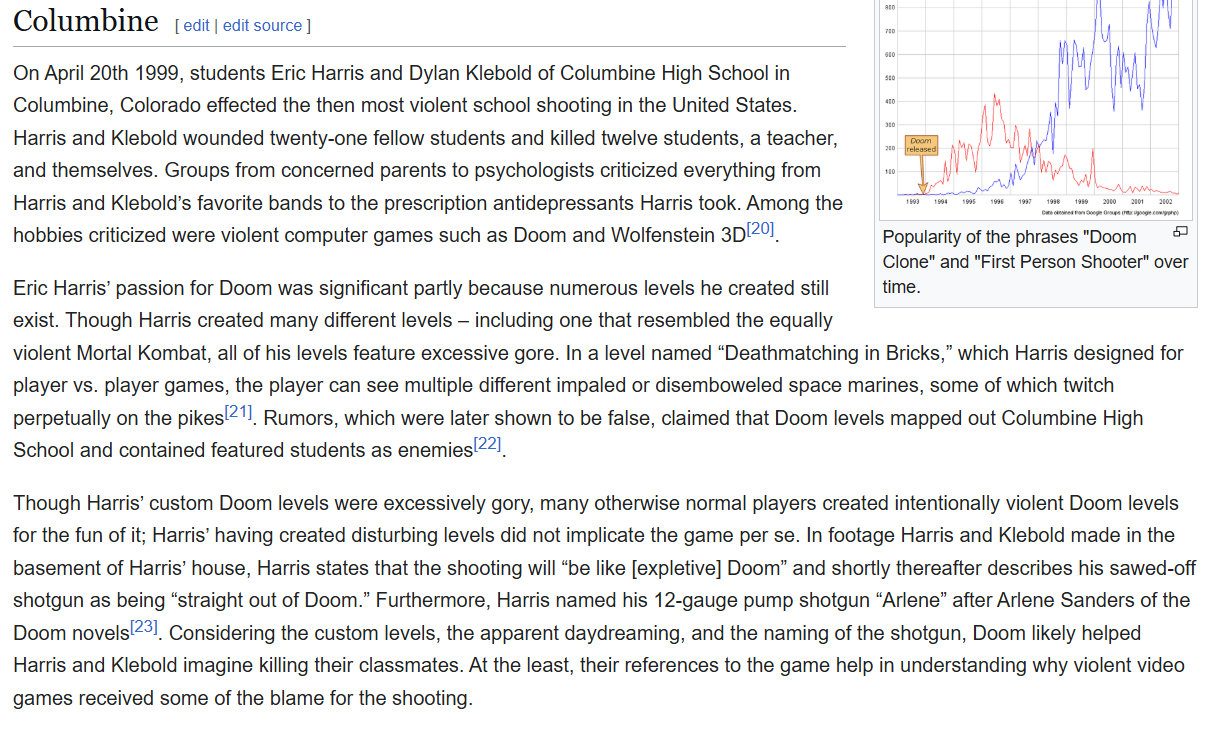

The Columbine Tragedy

This controversy reached its tragic apex in 1999. Following the horrific Columbine High School massacre, it was discovered that the two perpetrators had been avid Doom players. In the ensuing media frenzy, Doom was vilified. It was incorrectly reported that one of the shooters had designed Doom levels that were a replica of the school to practice his attack.

While this was proven to be false (his levels were standard, if morbid, custom maps), the association stuck. Id Software was named, alongside other game and film companies, in a $5 billion lawsuit (e.g., Sanders v. Acclaim Entertainment) filed by the victims’ families, alleging that their violent products were a cause of the tragedy. The case was ultimately dismissed by the court, which cited First Amendment protections (Source).

Doom became Exhibit A in the long-running, contentious debate over the link between video games and real-world violence, a shadow that would hang over the industry for years.

Chapter 8: The Enduring Legacy – Rip and Tear

The legacy of Doom is almost impossible to overstate. It is not just a retro curiosity; it is a living, breathing part of gaming culture.

- The Sequels: Id quickly followed up with Doom II: Hell on Earth (1994), which didn’t change the engine but introduced the iconic Super Shotgun and a host of new monsters. The Ultimate Doom (1995) added a fourth episode, and Final Doom (1996) provided two more full-length campaigns.

- The Source Code Release: In 1997, John Carmack, in a move that was both generous and characteristic, released the original Doom source code to the public for free. This was a monumental event. It allowed programmers to understand how the engine worked and, more importantly, to port it to new systems and enhance it. This gave birth to “source ports” (like ZDoom, GZDoom, and PrBoom) that allow modern players to play Doom on any operating system with high resolutions, mouse-look, and other features.

- The Hacker’s Challenge: Because the source code is available and the original game was so efficient, it became a running joke and a rite of passage for programmers to get Doom to run on any device with a screen. This includes digital cameras, iPods, printers, ATMs, the MacBook Pro Touch Bar, and even, through clever hacking, a digital pregnancy test.

- The Reboots: The franchise has been reimagined twice. Doom 3 (2004) was a cutting-edge, slow-paced survival horror game. But it was the 2016 reboot, DOOM, that brought the series back to its roots. By focusing on “push-forward combat” and blistering speed, it recaptured the pure, adrenaline-fueled gameplay of the original and was a massive critical and commercial success, followed by the equally lauded Doom Eternal (2020).

More than anything, Doom represented a paradigm shift (Source). It proved that the PC was a viable, even superior, platform for action gaming. It demonstrated the power of digital distribution and the importance of fostering a creative community. It was a punk rock statement—a raw, loud, and unapologetic burst of creative energy that came not from a corporate boardroom but from a small group of brilliant, rebellious creators.

It was, and is, a masterpiece. A perfect storm of groundbreaking technology, inspired design, and revolutionary business sense that didn’t just push the envelope—it ripped and tore it to shreds.

If you enjoyed this deep dive into Doom, be sure to check out our other entries in the series. We’ve covered the grisly arcade mayhem of Splatterhouse, the futuristic brutality of Death Duel, and the unforgettable JRPG magic of Lunar: Silver Star and Eternal Blue. Each article captures a different slice of gaming history, and together they tell the story of how these classics shaped the eras they came from. Oh yeah, we dug deep into Double Dragon as well.

Retro Replay Retro Replay gaming reviews, news, emulation, geek stuff and more!

Retro Replay Retro Replay gaming reviews, news, emulation, geek stuff and more!